Polynesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): The …

Years: 909BCE - 819

Polynesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): The Post-Lapita Ocean — Navigation Perfected and Worlds Awaiting Settlement

Regional Overview

Across the heart of the Pacific, the first millennium BCE to the early first millennium CE marked the transformation of Polynesia from an idea in motion — the open ocean itself — into a system of distinct cultural and ecological zones.

By this age, the Lapita legacy of seafaring, horticulture, and ornament had matured into the classical Polynesian navigational and genealogical complex.

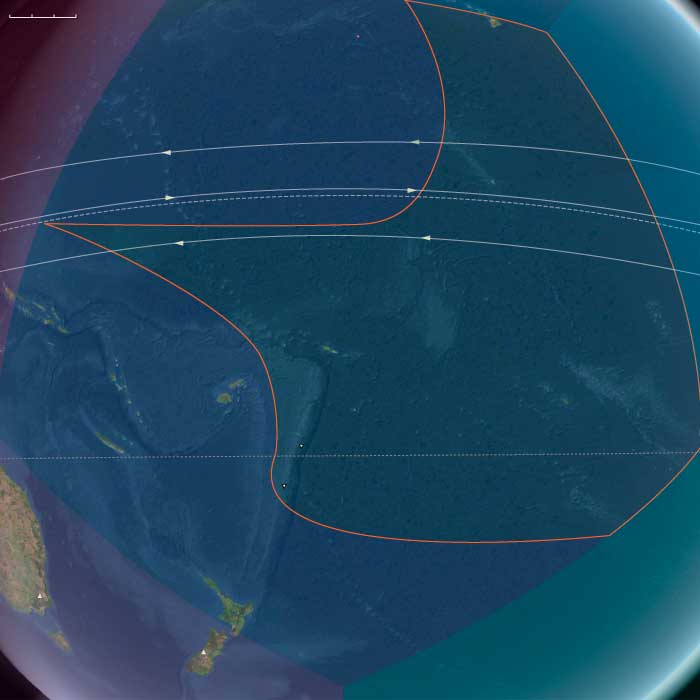

The great triangle of future Polynesia was taking recognizable form: West Polynesia—anchored in Tonga and Samoa—was fully settled; East Polynesia, though distant, was now within the reach of long-range exploration; and North Polynesia (the Hawaiian chain) remained on the horizon of voyaging knowledge, its high islands still untouched by human settlement but already “seen” in oral cartographies of the sea.

Geography and Environment

The Polynesian ocean forms a single ecological field: volcanic high islands with fertile soils, reef-fringed lagoons, and far-flung low atolls.

Climates varied from humid tropical in the Samoan–Tongan cores to cool-temperate in future New Zealand’s approaches, but winds and currents — especially the steady southeast trades and seasonal westerlies — unified the region.

These conditions produced both navigational stability and ecological diversity: breadfruit and taro belts in the high islands, pandanus and coconut groves on the atolls, and vast seabird rookeries in the unpeopled margins of the north and east.

Voyaging and Cultural Transformation

By the late first millennium BCE, Polynesian sailors had transformed Lapita technologies into the refined double-hulled waka and vaka fleets that could traverse thousands of kilometers.

In West Polynesia, societies of Tonga and Samoa consolidated post-Lapita chiefdoms, formalizing kin hierarchies and ritual systems that would radiate outward for centuries.

These communities perfected the star compass, the reading of swells and clouds, and the ceremonial training of navigators — the mental maps that later carried voyagers to the far frontiers.

From this vigorous center, exploratory voyages fanned eastward across the central Pacific. The Cook, Society, and Marquesas islands were probed during this epoch; early landfalls at Rapa Nui and Pitcairn–Henderson may have occurred by its close. East Polynesia thus entered history as a zone of reconnaissance and sporadic occupation — a place of ancestral names and scattered settlements.

To the north, long-distance routes from Samoa or the Marquesas pointed toward an immense chain yet unseen: the Hawaiian Islands.

North Polynesia, though uninhabited, was already part of navigational speculation — the horizons of knowledge that foreshadowed later colonization.

These empty archipelagos held the most pristine ecosystems of the Pacific: uncut forests, bird-filled valleys, and coral lagoons at peak productivity.

Subsistence and Material Foundations

The Polynesian economy rested on a portable landscape: root crops (taro, yam, sweet potato), tree crops (breadfruit, coconut, pandanus), and commensal animals (pig, dog, chicken).

In West Polynesia these formed intensively managed agro-forestry mosaics, integrating irrigated taro terraces and dryland yam fields with orchard belts and coastal fish weirs.

Canoe construction drew on vast breadfruit and tamanu forests; the trade of adze stone, shell ornaments, and tapa cloth circulated through the region.

Farther east and north, these same domesticated species would later transform newly settled islands into productive ridges-to-reef systems.

Belief and Symbolism

Religion and cosmology were inseparable from navigation and kinship.

Deities of the sea and sky, ancestral voyagers, and tutelary spirits governed each landfall.

In Tonga and Samoa, the foundations of the ariki and matai hierarchies were already sanctified by genealogy; marae and ahu platforms appeared as foci of ritual.

These traditions carried forward into the emerging East Polynesian ceremonial landscapes — the prototypes of later megalithic temple architecture on Tahiti, Hawaiʻi, and Rapa Nui.

Adaptation and Resilience

Diversified food webs, arboriculture, and extensive social exchange made West Polynesian societies resilient to cyclones and droughts.

Ritualized redistribution (feasting, gift exchange) balanced inequality and sustained inter-island alliance.

For the yet-unsettled archipelagos, resilience took ecological form: intact seabird nutrient cycles and volcanic soils awaited human arrival.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 819 CE, Polynesia was conceptually complete though geographically unfinished.

West Polynesia’s complex chiefdoms stood as the cultural engine; East Polynesia represented the frontier of expansion; North Polynesia remained the pristine terminus yet to be reached.

The region’s unity lay in its oceanic intelligence — the ability to transform stars, swells, and birds into a navigational architecture that bound scattered islands into a coherent world.

When later centuries brought the great settlement wave — into Hawaiʻi, Aotearoa, and Rapa Nui — those societies would express, in monumental form, the spiritual and ecological templates already perfected during this formative epoch.

Thus, Polynesia’s early history demonstrates precisely how a vast region divides naturally into distinct but interdependent subregions — each carrying a portion of the same ocean-born civilization.