Polynesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene …

Years: 7821BCE - 6094BCE

Polynesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Thermal Optimum Seas and Islands in Equilibrium

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Early Holocene, Polynesia—extending from the Hawaiian archipelago across Samoa, Tonga, and the Society Islands to the still-forming volcanic ridges of what would become Rapa Nui and Pitcairn—remained entirely unpeopled yet ecologically self-organized.

The global thermal optimum (c. 8,000–6,000 BCE) raised sea-surface temperatures and stabilized wind and current systems across the tropical Pacific.

High islands such as Oʻahu, Tahiti, and Savaiʻi bore deep belts of cloud forest, while their leeward coasts supported expanding reef-lagoon mosaics.

Emergent atolls and carbonate platforms—Tuvalu, Tokelau, and Midway—stood as low, gleaming rims on a still-rising ocean, already threaded by trade-wind-driven nutrient circuits.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Early Holocene Optimum produced the warmest and most stable Pacific climate of the Quaternary.

-

Sea levels continued their post-glacial rise, reaching only a few meters below present; newly drowned coastal shelves became lagoons and barrier-reef arcs.

-

Trade winds and monsoonal convergence zones settled into predictable rhythms, ensuring orographic rain on windward mountains and long dry seasons on leeward coasts.

-

ENSO activity was weak or absent; the Pacific climate engine ran with near-mechanical reliability.

These steady conditions allowed ecosystems to mature without major disturbance for more than a millennium.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (Before Human Arrival)

Polynesia at this stage was a realm of maximal endemic richness and ridge-to-reef productivity:

-

Forests: dense montane and mesic stands of hardwoods, Pandanus, and tree ferns cloaked volcanic slopes; lowlands carried palm and coastal scrub communities.

-

Freshwater systems: perennial streams sculpted alluvial fans and fed wetland complexes behind beach ridges—later to become ideal taro-pond basins.

-

Reefs and lagoons: coral growth kept pace with sea-level rise; fish biomass, clam beds, and crustacean diversity peaked; guano from seabird colonies fertilized nearshore flats.

-

Seabird rookeries blanketed outer islets, coupling marine nitrogen to terrestrial fertility.

-

Atolls and low islands: thin soils supported grasses, heliotropes, and mangrove thickets along brackish lagoons—incipient blueprints for future habitation.

Geomorphic and Oceanic Processes

A gentle post-glacial transgression reshaped Polynesia’s coastlines: drowned river mouths became estuaries and bay-head deltas; reef crests migrated upward; mangroves and peat lenses accumulated behind storm ridges.

Volcanic islands such as Hawaiʻi Island, Tahiti, and Rarotonga continued to build and erode simultaneously, feeding rich sediment to deltas.

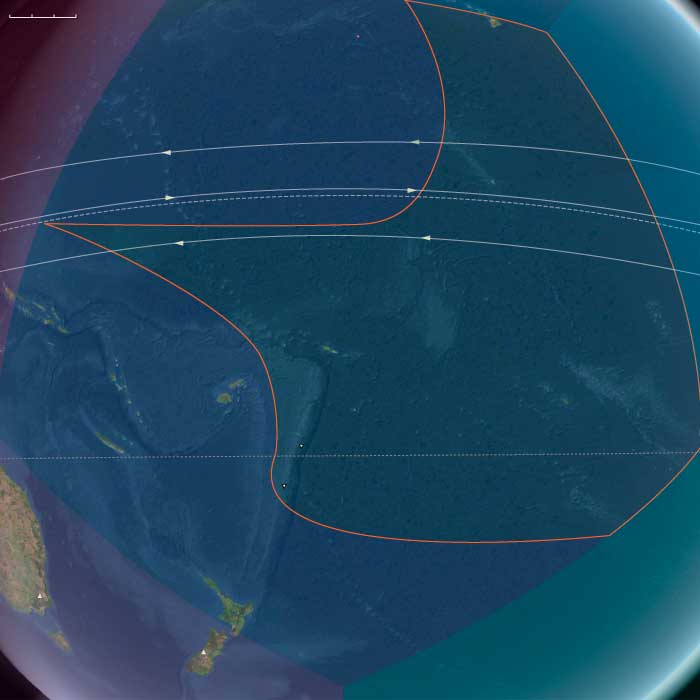

Across the central Pacific, the South Equatorial Current and its counterflows organized enduring biological highways, prefiguring the navigation corridors of future voyagers.

Regional Profiles

-

North Polynesia (Hawaiian chain except Hawaiʻi Island): Warm seas and reliable trades sustained lush cloud-forest belts, valley wetlands, and stable lagoon fisheries.

-

West Polynesia (Hawaiʻi Island, Samoa, Tonga, Society Islands, Cook Islands, Tuvalu–Tokelau, Marquesas): Reef–valley coupling reached perfection—mountain rainfall feeding coastal productivity.

-

East Polynesia (Pitcairn group, Rapa Nui, and outlying ridges): Newly emergent volcanic highlands and surrounding seamounts hosted pioneer flora—ferns, grasses, and mosses—and rapidly accreting coral rims.

Together these arcs formed a climatic and ecological continuum, unbroken by storm or current.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Without humans, natural feedback loops maintained equilibrium:

-

Cloud-forest evapotranspiration recycled rainfall; mangroves trapped sediment and built new ground.

-

Coral reefs tracked sea-level rise through vertical accretion, preserving lagoon depth and productivity.

-

Seabirds, turtles, and migratory fish redistributed nutrients across thousands of kilometers.

Disturbance—occasional cyclone or lava flow—was localized and quickly absorbed, strengthening rather than destabilizing ecosystem complexity.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Polynesia had reached its pre-human ecological zenith.

Across every island chain, the ridge-to-reef continuum—from cloud forest to stream to reef flat—operated in perfect balance.

These conditions provided the environmental templates for later Polynesian agriculture, aquaculture, and navigation.

The Early Holocene thus marked an age of formation rather than transformation—a prolonged prelude in which the ocean composed its stage for the human voyaging worlds to come.