West Polynesia (676–819 CE): Chiefly Consolidation, Monumental …

Years: 676 - 819

West Polynesia (676–819 CE): Chiefly Consolidation, Monumental Beginnings, and Oceanic Networks

Geographic & Environmental Context

West Polynesia—comprising Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, Society Islands, and the Marquesas—formed the cultural and navigational heartland of Polynesia. High volcanic islands such as Tongatapu, Upolu, and Tahiti contrasted with coral atolls and reef islands that relied on lagoon and breadfruit ecologies. Reliable rainfall, fertile volcanic soils, and protected lagoons supported intensive arboriculture and horticulture.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

A mid-Holocene stability continued. Regular southeast trades and modest ENSO variability ensured dependable breadfruit and taro yields. Reef fisheries thrived, while volcanic slopes supported yam, banana, and taro gardens.

Subsistence & Settlement

Extended kin groups cultivated irrigated taro, maintained breadfruit groves, and herded pigs and chickens. Settlements clustered along coastal flats, with stone terraces, raised mounds, and canoe landings. Lagoon and offshore fishing remained central, employing outriggers, nets, and fish traps.

Technology & Material Culture

Polished adzes, basalt pounders, and shell ornaments show refinement in craft specialization. Canoe technology—double-hulled voyaging vessels with lashed-lug hulls and mat sails—reached peak sophistication, allowing routine inter-island travel. Fine tapa cloth and shell jewelry expressed rank distinctions.

Society & Political Structure

By the 700s, chiefly hierarchies (’eiki, ali‘i) coalesced around sacred genealogies linking leaders to gods and ancestors. Tonga emerged as the most stratified polity, with monumental mounds (langi) and raised tombs signaling the early Tu‘i Tonga dynasty’s rise. Samoa maintained a council-based chiefly system (matai), emphasizing ritual consensus rather than divine kingship. The Society and Cook Islands mirrored these dual traditions—strong hereditary titles balanced by lineage councils.

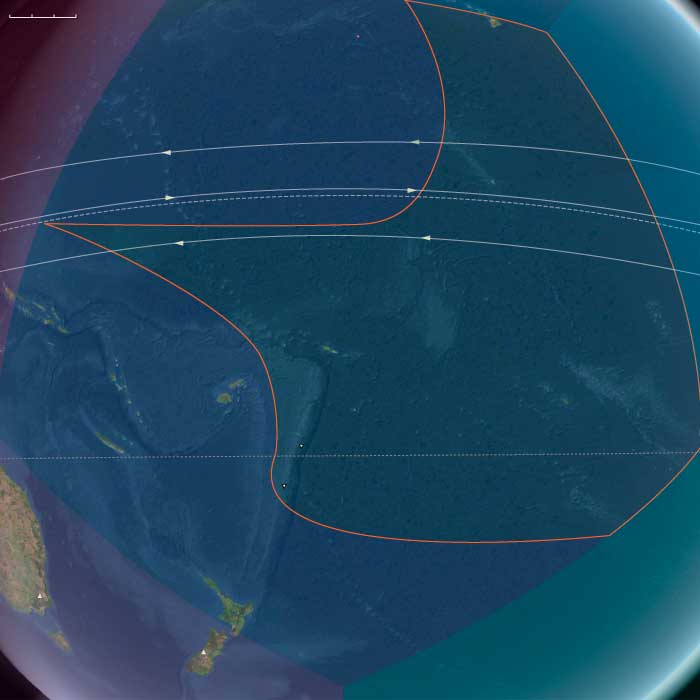

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Voyagers regularly crossed the Tonga–Samoa–Fiji triangle, distributing basalt tools, shell valuables, and marriage alliances. Long-distance expeditions to Tuvalu and Tokelau linked high islands to atolls through kin ties. Canoes moved food crops, pigs, and cultural motifs such as the Tongan kava rite and Samoan oratory conventions.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Stone platform tombs, earthworks, and sacred enclosures (marae, malae) framed ritual life. Genealogical chants preserved chiefly descent; dances and oratory celebrated alliances and divine ancestry. The cosmos was envisioned as layered: the sea as a realm of spirits, the sky as ancestral heaven. Sacrificial rites, kava ceremonies, and tattooing reaffirmed sacred rank and community solidarity.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Crop diversification (taro, yam, breadfruit, banana) and arboriculture buffered droughts. Coral-fishing management sustained lagoon ecosystems. The dual economy—coastal horticulture and offshore voyaging—ensured resilience across climatic shifts.

Transition

By 819 CE, West Polynesia had matured into a network of stratified chiefdoms—the Tongan state already centralizing power, Samoan and Society Island systems elaborating ceremonial leadership, and a shared Polynesian identity spreading outward through trade, kinship, and ritual exchange.