Polynesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Paleolithic …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Polynesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Paleolithic I — Volcanic Arcs, Reef Foundations, and the Architecture of Isolation

Geographic & Environmental Context

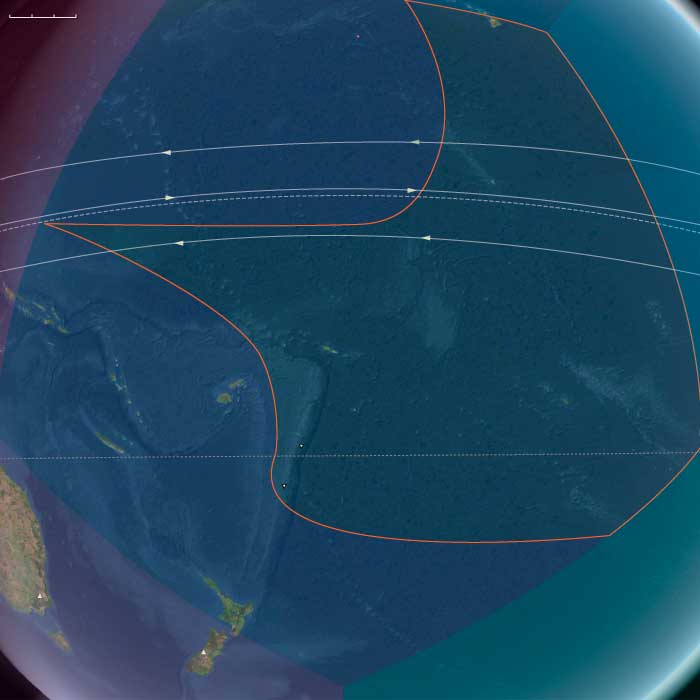

During the later Pleistocene, the Polynesian sector of the Pacific was a scattered domain of volcanic peaks, emerging atolls, and widening reef flats—a geography still entirely devoid of humans but already constructing the natural architecture that would one day sustain them.

The region spanned three great arcs of islands:

-

The Hawaiian–Emperor chain in the north, including Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, Kauaʻi, Niʻihau, and Midway, where high volcanic forms dominated the subtropics.

-

The central–western archipelagos—Tonga, Samoa, the Cook and Society Islands, the Marquesas, Tuvalu, and Tokelau—a mixture of high volcanic islands, raised limestone platforms, and embryonic atolls.

-

The eastern fringe—future Pitcairn and Rapa Nui—where lone volcanic edifices rose from deep ocean basins, linked only by the great South Pacific gyres and currents.

Sea level stood ~100 m lower than today, exposing vast coastal benches and broad shelves around high islands. Many modern lagoons lay dry, their reef rims fossilized in the air; others built episodically with interglacial warm phases. Across the region, reef, volcano, and ocean interacted in long cycles of uplift and subsidence—the slow choreography that would, over tens of millennia, produce the Polynesian Triangle’s intricate geography.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The epoch was framed by full glacial conditions—cooler sea-surface temperatures, stronger trade winds, and a sharply defined dry season.

-

Atmosphere and Ocean: Strengthened trades drove upwelling along many leeward coasts, favoring cool, nutrient-rich nearshore waters. Seasonal dust episodes and winter surf reworked coastal benches, while the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) oscillated northward and southward with orbital rhythms.

-

Late-Glacial Variability: Even within the long glacial, brief mild interstadials brought short-lived reef growth spurts and pulses of vegetation recovery. Cooler phases depressed the coral-algal community but expanded coastal steppe and dry scrub.

-

Volcanic Activity: Continuous effusive volcanism in the Hawaiian Big Island and intermittent eruptions in the Societies, Marquesas, and Cooks rejuvenated landscapes, built fresh lava plains, and created ephemeral crater lakes and ash-fed soils.

Overall, Polynesia’s climate oscillated between cool, windy glacial stability and short warming pulses that allowed the reef crest and forest line to advance and retreat in rhythm with the global climate.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (No Human Presence)

Every island was its own closed laboratory of evolution.

-

Marine Life:

Coral communities fluctuated with sea level and temperature, but even under glacial suppression, shallow fringing reefs persisted. Fish, mollusk, turtle, and seabird populations were immense, their only predators sharks and seals. On outer banks like Midway, Tokelau, and Tuvalu, monk seals and turtles bred in numbers far exceeding modern densities. -

Terrestrial Life:

The higher islands—Hawaiʻi, Tahiti, Samoa, the Marquesas—carried dense montane forests in windward belts and dry woodland or grass steppe on leeward slopes. Cloud forests crowned the summits, capturing mist even under glacial dryness. Each island hosted unique, isolated assemblages of birds, insects, and plants, evolving in splendid isolation. -

Avian Realms:

Seabird supercolonies occupied cliffs and stacks, fertilizing soils with guano and enriching nearshore ecosystems. On atolls and cays, the air was dense with terns, boobies, and petrels—an avian kingdom uninterrupted by human disturbance.

Environmental Processes & Dynamics

-

Reef and Lagoon Evolution: Lower sea levels exposed broad reef flats, which weathered into limestone benches; with each brief warming, corals recolonized and built new terraces—a staircase of future lagoons.

-

Volcano–Erosion Cycles: Heavy rainfall on high islands carved deep amphitheaters (e.g., Waiʻanae, Koʻolau, and Tahiti’s ancient calderas), while aridity on leeward slopes preserved lava plains and dunes.

-

Marine Productivity: Upwelling zones around island chains created feeding grounds for pelagic fish and whales; kelp-like macroalgae likely formed dense nearshore beds in cooler zones, anchoring early “reef forest” ecologies.

-

Atmospheric Circulation: Persistent trades sculpted the cloud belts that would later define Polynesian ecological duality—lush windward valleys and dry leeward coasts.

Long-Term Significance

By 28,578 BCE, Polynesia’s physical and biological foundations were firmly in place:

-

Volcanic arcs had matured into high-island chains with deep, fertile amphitheaters and developing river networks.

-

Coral reef systems, though suppressed by glacial cooling, had established their long-term frameworks, ready to surge during Holocene sea-level rise.

-

Forest and reef ecologies had stabilized into enduring zonations—ridge forests, dry scrub, coastal strand, reef-flat, and pelagic edge—that would persist through the Holocene.

The epoch thus created Polynesia’s essential blueprint: a world of towering volcanic islands, expanding reef terraces, seabird-sustained fertility, and unbroken ecological isolation.

In the ages to come, these formations would become the living stage for one of Earth’s greatest human voyaging traditions—a future civilization built upon the deep-time architecture of glacial Polynesia.