Polynesia (4,365 – 2,638 BCE): Late Neolithic …

Years: 4365BCE - 2638BCE

Polynesia (4,365 – 2,638 BCE): Late Neolithic — Predictable Seas and Awaiting Worlds

Geographic & Environmental Context

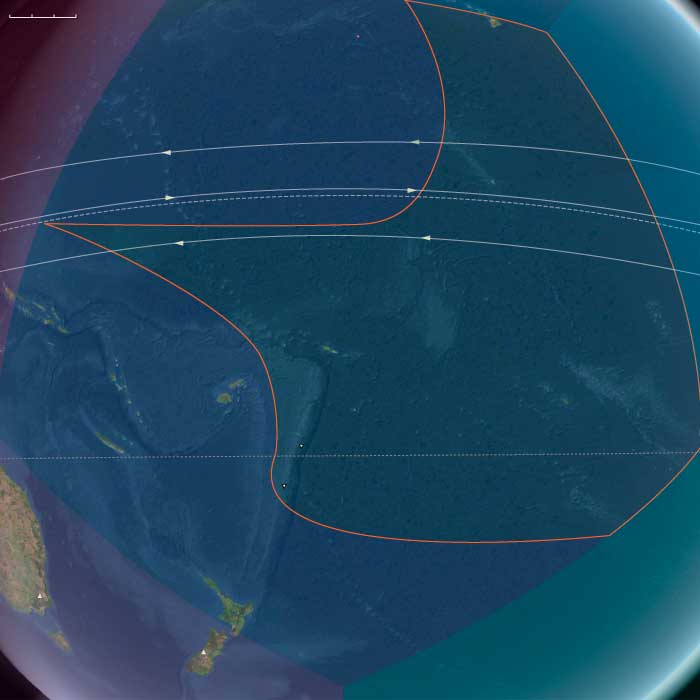

Polynesia spans a vast triangle across the central and eastern Pacific, encompassing three distinct environmental realms:

-

North Polynesia, including the Hawaiian Islands chain (except Hawaiʻi Island) and Midway Atoll.

-

West Polynesia, extending from Hawaiʻi Island through Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu, Tokelau, the Cook Islands, the Society Islands, and the Marquesas.

-

East Polynesia, comprising the Pitcairn Islands and Easter Island (Rapa Nui).

Across this expanse, volcanic high islands alternated with atolls and raised coral platforms, forming ecological mosaics of ridges, streams, lagoons, and reefs.

In the west and north, basaltic uplands captured trade-wind rains, while eastern islands—more isolated and younger—remained sparsely vegetated and edged by nutrient-rich marine shelves.

Each island system formed a self-contained world linked by atmospheric rhythms and the open ocean’s consistent pulse.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Throughout this epoch, the Pacific trade-wind system stabilized, its regularity shaping future patterns of navigation.

-

In North Polynesia, gentle but persistent rainfall sustained perennial streams; winter surf reworked reef passes and sand spits.

-

In West Polynesia, inter-island visibility and seasonal swell windows became predictably cyclical, forging the basis of later star-path navigation.

-

In East Polynesia, the South Pacific Gyre moderated temperatures and rainfall, while weak ENSO variation fostered long-term stability in coastal processes.

The overall climate pattern was one of gentle equilibrium—ideal for the development of ridge-to-reef ecosystems later adapted to human use.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (before human arrival)

All three subregions remained uninhabited during this epoch.

-

North Polynesia’s humid valleys nourished dense ferns and native forests whose runoff enriched productive reefs and lagoons.

-

West Polynesia maintained high-diversity reef crests, extensive seabird rookeries, and intact coastal woodlands.

-

East Polynesia’s young volcanic soils bore pioneer grasses and shrubs, while seabirds and marine mammals formed nutrient linkages across land and sea.

In each, avian colonies and reef systems underpinned ecological productivity, generating food webs that would later sustain human settlement. The interdependence of ridge, stream, and reef defined a continuum of life stretching from mountain mist to coral flat.

Societies and Political Developments

No permanent human communities yet occupied Polynesia. The landscapes existed as ecological laboratories, refining the environmental patterns that would later shape human adaptation.

Isolated from continental biomes, these islands evolved as closed systems, each displaying an early balance between soil formation, plant succession, and marine fertility—conditions that would invite settlement millennia later.

Economy and Trade

Absent of humans, there was no economy or trade in the human sense; yet natural exchanges thrived.

Guano from seabirds fertilized uplands, basaltic runoff fed nearshore plankton blooms, and seasonal upwelling transported marine nutrients across thousands of kilometers.

These were the proto-economies of nature—flows of energy and matter that prefigured the human cultivation and exchange systems of the later Holocene Pacific.

Belief and Symbolism (prospective foundations)

Though uninhabited, Polynesia’s landscapes already held symbolic potential.

Towering volcanic peaks, thundering surf, and the night sky’s unbroken clarity formed the visual grammar that would later underlie Polynesian cosmology—the concept of a living ocean, sky pathways, and island genealogies rooted in stone and star alike.

The geography itself preserved the template for sacred space, awaiting the narratives that human voyagers would eventually inscribe upon it.

Adaptation and Resilience

These ecosystems demonstrated extraordinary resilience.

Windward forests regenerated after storms; coral reefs recovered rapidly from sediment influx; atoll lagoons adjusted dynamically to sea-level fluctuations.

The feedback systems that stabilized these islands over millennia created a naturally buffered environment—one later mirrored by Polynesian ridge-to-reef stewardship practices such as loʻi kalo irrigation and loko iʻa fishpond construction.

Long-Term Significance

By 2638 BCE, Polynesia’s seas, skies, and island chains had matured into one of Earth’s most predictable and interconnected oceanic systems.

Its climatic stability, ecological richness, and clear navigational horizons provided the perfect preconditions for human exploration.

When settlement finally came, Polynesian societies would inherit not a wilderness, but a finely tuned set of living laboratories—each island a self-sustaining microcosm of the Pacific world, pre-adapted for the synthesis of ecology, navigation, and culture that would define Oceania’s later civilizations.