Polynesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

Polynesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene Transition — Emerging Arcs, Drowned Plateaus, and Reef Foundations

Geographic & Environmental Context

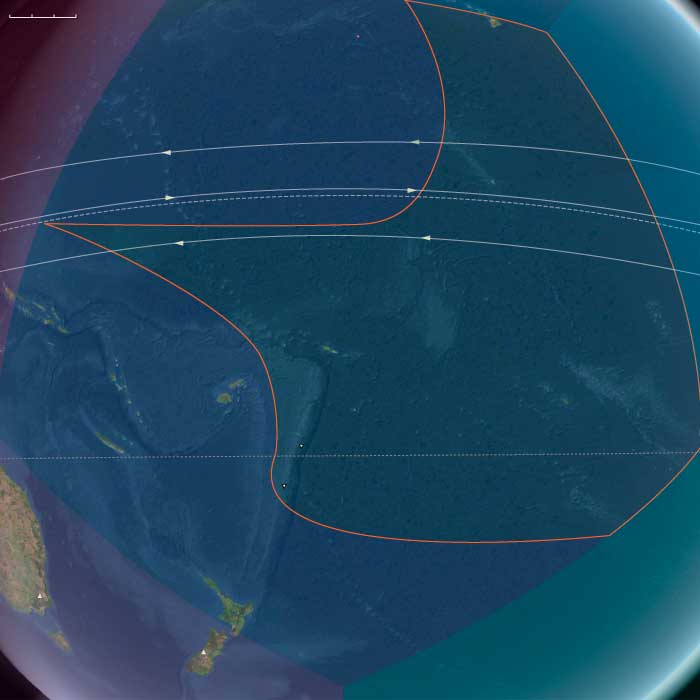

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Polynesia—stretching from the Hawaiian archipelago across Samoa, Tonga, the Cook and Society Islands, to the far eastern outliers of Pitcairn and Rapa Nui—remained entirely unpeopled, a scattered constellation of volcanic and reefed islands rising above the world’s largest ocean.

At the Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500–19,000 BCE), global sea levels stood more than 100 m lower than today, exposing wide coastal shelves and tightening inter-island channels. As ice sheets melted, deglaciation flooded ancient shorelines, transforming basins into lagoons and seamounts into isolated atolls.

-

North Polynesia (Oʻahu, Maui Nui, Kauaʻi–Niʻihau, Midway Atoll): the Maui Nui shelf—once a single island—became a cluster of channels; Midway’s rim expanded as new lagoons formed.

-

West Polynesia (Hawaiʻi Island, Tonga, Samoa, Tuvalu–Tokelau, Cook, Society, and Marquesas): reefs and barrier lagoons built up around volcanic peaks, while low atolls appeared as sea level rose.

-

East Polynesia (Pitcairn, Rapa Nui, and nearby seamounts): the farthest outposts of the Pacific, geologically young and ecologically self-contained, fringed by narrow reef flats and rich upwelling zones.

Across this immense realm, oceanic currents—the South and North Equatorial and the Kuroshio–Equatorial Counter-flow system—created predictable gyres, establishing the hydrological backbone that would later sustain Polynesian voyaging.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The epoch was one of oscillation and renewal:

-

Last Glacial Maximum (26,500–19,000 BCE): cooler seas and exposed shelves expanded coastal plains; coral growth slowed under lowered sea level.

-

Bølling–Allerød interstadial (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): warmth and rainfall increased; reefs surged upward in “catch-up” growth; lagoons and barrier formations matured.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): brief cooling flattened reef accretion and restricted mangroves; trade-wind aridity spread in leeward belts.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): steady warming and sea-level stabilization allowed coral terraces, mangroves, and strand forests to reach near-modern equilibrium.

By 7822 BCE, the Pacific climate engine had achieved its Holocene rhythm—warm, humid, and oceanically stable.

Biota & Baseline Ecology (No Human Presence)

Polynesia’s ecosystems reached pristine balance under rising seas:

-

Reefs and lagoons flourished with coral, mollusks, crustaceans, and reef fish (parrotfish, surgeonfish, mullet); spur-and-groove structures and back-reef ponds became marine nurseries.

-

Coastal vegetation—pandanus, beach heliotrope, ironwood, and grasses—rooted in guano-enriched sands; strand forests stabilized dunes.

-

Cloud-forests cloaked high islands such as Tahiti and Savaiʻi, while dry leeward slopes supported shrub and palm mosaics.

-

Seabirds nested in immense colonies; turtles hauled out on beaches; marine mammals frequented newly formed bays.

All existed in predator-free isolation, each island a laboratory of speciation and resilience.

Geomorphic & Oceanic Processes

As the sea rose, island landscapes underwent continuous re-sculpting:

-

Reef accretion kept pace with transgression, forming the first true atoll rings.

-

Maui Nui’s plateau fragmented into separate islands; Hawaiʻi Island’s volcanic plains met new coasts.

-

Eastern high islands (Rapa Nui, Pitcairn) gained fertile volcanic soils through slow weathering; storm surges and wave reworking created terraces and embayments.

-

Sediment deltas at stream mouths formed early estuarine wetlands—future sites for Polynesian fishponds and irrigated terraces.

Symbolic & Conceptual Role

For millennia these lands remained beyond the human horizon—unimagined yet forming the ecological architecture that would one day welcome voyagers. Their mountains, lagoons, and reefs became the stage on which later Polynesian societies would enact origin stories of sea and sky.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Natural resilience was inherent:

-

Coral reefs tracked rising seas through vertical growth, preventing ecological collapse.

-

Guano-fertilized soils accelerated vegetative colonization after storm disturbance.

-

Cloud-forest hydrology maintained water flow even in drier pulses.

These feedbacks produced long-term equilibrium between land, sea, and atmosphere—the defining ecological rhythm of Polynesia.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Polynesia had become a fully modern oceanic system: drowned plateaus transformed into lagoons and atolls; coral terraces and forest belts stabilized; seabird and reef ecologies reached peak diversity.

Though still empty of humankind, the region now possessed every element—predictable currents, fertile reefs, sheltered bays, and stable climates—that would, tens of millennia later, make it the natural cradle of the world’s greatest voyaging tradition.