Polynesia (1252–1395 CE) Voyaging Commonwealths and …

Years: 1252 - 1395

Polynesia (1252–1395 CE)

Voyaging Commonwealths and Island Ecologies

Geographic & Environmental Framework

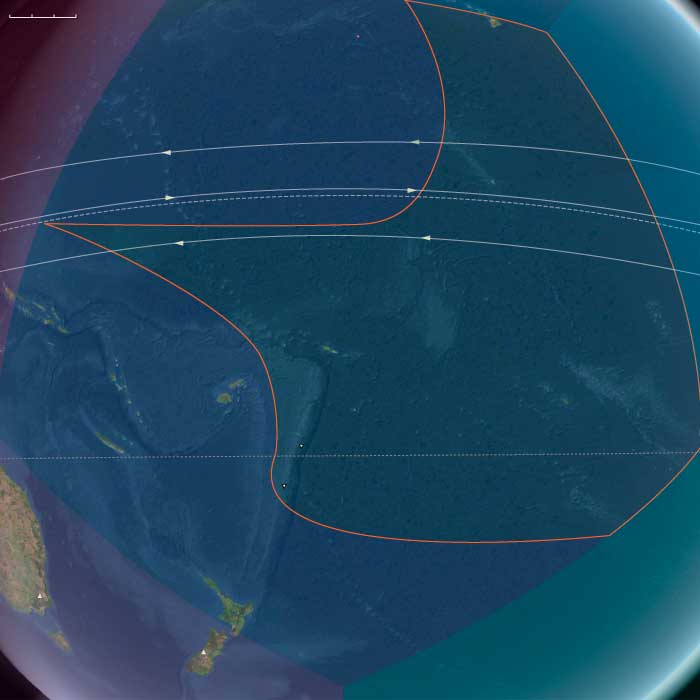

Polynesia in the Lower Late Medieval Age stretched across the central and eastern Pacific—from the volcanic high islands and atolls of Hawaiʻi, Samoa, Tonga, and the Societies to the far eastern outliers of Rapa Nui and Pitcairn–Henderson.

High volcanic islands such as Hawaiʻi, Tonga, and Tahiti sustained fertile valleys, leeward drylands, and reef-lined coasts; low atolls like Tuvalu and Tokelau depended on coconut and breadfruit arboriculture.

This vast oceanic domain formed a connected world of voyaging, ritual, and ecological engineering, bound by canoe routes, genealogies, and shared ritual centers such as Taputapuātea on Ra‘iātea.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The waning Medieval Warm Period and onset of the Little Ice Age (from c. 1300 CE) brought cooler seas and rainfall variability:

-

High islands: alternated between drought and flood years, but diversified agriculture and irrigation stabilized production.

-

Atolls: faced heightened risk from storm surges and prolonged dry spells.

-

Eastern margins (Rapa Nui–Pitcairn): isolation deepened as cooler currents and winds curtailed long-range voyaging.

Despite these shifts, Polynesian societies demonstrated remarkable resilience through integrated ridge-to-reef economies and adaptive governance.

Societies & Political Developments

North Polynesia – Hawaiian Chiefdoms:

-

On Oʻahu, Maui, and Kauaʻi, chiefly hierarchies (aliʻi nui) consolidated authority through control of irrigated valleys and coastal fishponds (loko iʻa).

-

Land divisions (ahupuaʻa) extended from mountain ridges to reefs, coordinating upland agriculture with nearshore aquaculture.

-

Monumental heiau temples, elaborate feather regalia, and the tightening of kapu laws affirmed chiefly sanctity and ecological control.

West Polynesia – Tongan, Samoan, and Society Polities:

-

The Tuʻi Tonga dynasty presided over a far-reaching maritime hegemony linking Samoa, the Cooks, and parts of the Societies through tribute and alliance.

-

Samoan federations balanced power among matai (titled chiefs) and orators, cultivating political stability through councils and ritual exchange.

-

The Society Islands centered on Ra‘iātea’s Taputapuātea marae, a sacred convocation site where chiefs renewed voyaging covenants and ritual genealogies.

-

In the Marquesas, valley chiefdoms grew populous, elaborating plaza architecture, tattooing, and carving traditions.

East Polynesia – Rapa Nui and Pitcairn–Henderson:

-

On Rapa Nui, lineage rivalries culminated in the great era of moai carving (13th–15th centuries); ancestral statues on coastal ahu embodied political legitimacy.

-

Deforestation and soil depletion signaled mounting ecological strain.

-

Pitcairn–Henderson societies declined as isolation severed exchange with Mangareva and the Societies, leading to eventual abandonment.

Economy & Exchange Networks

Across the region, intensive agro-aquatic production sustained large populations:

-

Irrigated taro terraces (loʻi kalo) in windward valleys, dryland field grids of sweet potato and yam on leeward slopes, and breadfruit–coconut arboriculture on atolls formed the subsistence base.

-

Fishponds and reef management ensured steady protein yields.

-

Trade circuits carried fine mats (ʻie tōga), red feathers, basalt adze blanks, pearl shell, and sennit cordage between Tonga, Samoa, the Cooks, and the Societies.

-

Long-distance voyaging diminished after 1300 CE, but ritual contact and shared myth maintained unity across the Polynesian triangle.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Hydraulic works: stone-lined irrigation ditches, check dams, and terrace mosaics maximized valley fertility.

-

Fishpond engineering: seawalls with mākāhā gates regulated recruitment and harvest cycles.

-

Canoe technology: double-hulled voyaging craft (waʻa kaulua) navigated by stars, swells, and seabird patterns.

-

Craft industries: basalt adze manufacture, barkcloth (kapa) production, and featherwork for chiefly regalia expressed technical and aesthetic sophistication.

-

Rapa Nui: megalithic quarrying and carving at Rano Raraku demonstrated unparalleled engineering using basalt and tuff.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Tonga–Samoa–Cooks–Societies arc: core political and ritual corridor of the Polynesian world, anchored by Taputapuātea.

-

Hawaiian channels: regular canoe routes bound Oʻahu, Maui, and Kauaʻi; voyages to Hawaiʻi Island maintained cultural unity.

-

Atoll shuttles: Tuvalu and Tokelau relied on canoe convoys to exchange salt fish and fiber goods for starch staples from high islands.

-

Eastern extremities: Rapa Nui and Pitcairn lay increasingly beyond active navigation but retained mythic presence in oral traditions.

Belief & Symbolism

Polynesian cosmologies joined ecology, lineage, and divine order:

-

Divine kingship in Tonga and Hawaiʻi linked chiefs to gods of sky and sea.

-

Taputapuātea ceremonies renewed voyaging oaths and sacred genealogies across archipelagos.

-

Kapu systems regulated fishing, planting, and social hierarchy, embedding environmental stewardship within religious law.

-

On Rapa Nui, moai and later the bird-man cult at Orongo expressed evolving balances between ancestor veneration and fertility ritual.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience strategies were ecological and institutional:

-

Diversified food webs—wet taro, dryland roots, arboriculture, fishponds, reef fisheries—buffered climatic shocks.

-

Ritual closures safeguarded spawning grounds; corvée labor rebuilt terraces and ponds after storms.

-

Inter-island reciprocity and marriage alliances redistributed surplus after droughts or cyclones.

-

On Rapa Nui, stone mulching and rock gardens extended cultivation as deforestation advanced.

Technology & Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

-

Expansion of chiefly estates and temple building intensified labor mobilization; intermittent warfare over land and prestige recurred across Oʻahu–Maui and among Tongan satellites.

-

Control of fishponds, irrigated valleys, and tribute networks defined chiefly authority.

-

Voyaging guilds and priestly lineages mediated disputes, maintaining overarching ritual unity despite political rivalry.

Transition (to 1395 CE)

By 1395 CE, Polynesia had matured into an archipelagic commonwealth of engineered landscapes and interlinked chiefdoms:

-

North Polynesia’s fishpond states and ahupuaʻa governance integrated mountain, valley, and reef.

-

West Polynesia’s Tuʻi Tonga hegemony and Taputapuātea rituals maintained trans-oceanic cohesion.

-

East Polynesia’s Rapa Nui monumentality marked both creative zenith and ecological vulnerability.

Together, these societies exemplified a Pacific synthesis of maritime mastery, ecological design, and sacred polity, resilient under the shifting climates of the early Little Ice Age and poised to evolve into the complex systems that Europeans would one day encounter.