Polynesia (1108 – 1251 CE): Voyaging Chiefdoms …

Years: 1108 - 1251

Polynesia (1108 – 1251 CE): Voyaging Chiefdoms and Sacred Landscapes

Between 1108 and 1251 CE, Polynesia reached a classical balance of seafaring mastery, hierarchical society, and ritual magnificence. Across a million square miles of ocean, island peoples transformed voyaging networks into enduring civilizations—chiefly orders on Hawaiʻi and Tonga, monumental artistry in Rapa Nui, and shared genealogies linking archipelagos from Samoa to the Marquesas. It was an era of stability under the long warmth of the Medieval Climate, when agriculture, navigation, and religion merged into one great maritime cosmology.

Geographic and Environmental Context

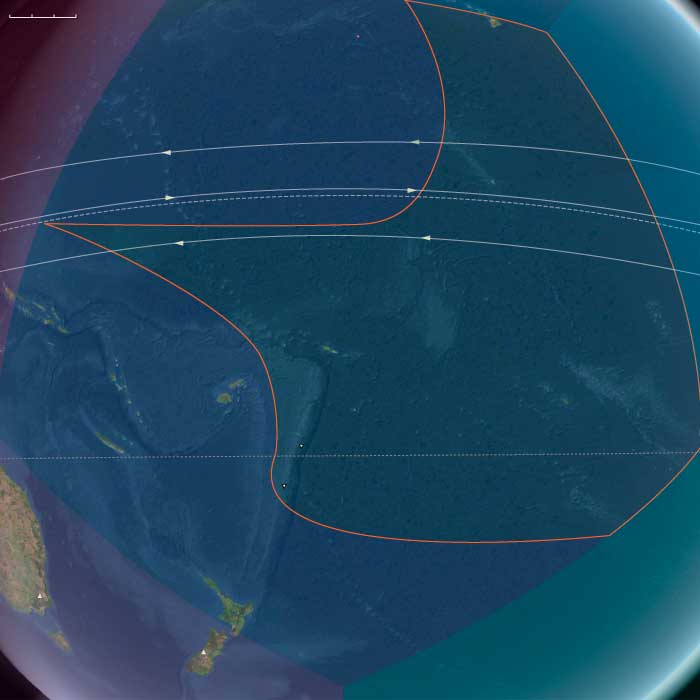

Polynesia spanned the tropical and subtropical Pacific triangle—from Hawaiʻi and Midway in the north, through Samoa, Tonga, and French Polynesia, to Rapa Nui and the Pitcairn–Henderson group in the far east.

High volcanic islands—Oʻahu, Tongatapu, Tahiti, Nuku Hiva, and Rapa Nui—combined fertile valleys with coral-fringed coasts, while atolls such as Tuvalu and Tokelau offered fishing grounds and coconuts but little arable soil.

Stable sea levels and dependable trade winds favored both intensive cultivation and sustained inter-island voyaging. The ocean was the binding geography: a living highway of canoes, reefs, and stars.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period provided a long interval of mild stability.

Rainfall patterns remained favorable, supporting irrigated taro terraces on high islands and breadfruit orchards along sheltered coasts.

Atolls, more exposed, faced drought and storm cycles but survived through exchange and mobility.

Occasional volcanic activity—most notably on Hawaiʻi’s Big Island—shaped settlement patterns and ritualized the landscape, embedding nature’s volatility within mythic order.

Across Polynesia, ecological diversity fostered resilience: valley irrigation, arboriculture, reef fisheries, and canoe networks together buffered climatic risk.

Societies and Political Developments

Polynesian society in these centuries was defined by the rise of ranked chiefdoms anchored in divine descent.

-

In Hawaiʻi, aliʻi (chiefs) governed under the sacred kapu system, commanding irrigation, labor, and temple construction. The great valleys of Oʻahu, Maui, and Kauaʻi became centers of population and authority, each ruled by high chiefs (aliʻi nui) whose power blended genealogy, mana, and redistribution.

-

In West Polynesia, Tonga achieved maritime hegemony under the Tuʻi Tonga dynasty, extending influence to Samoa, Fiji, and beyond through tribute, intermarriage, and ritual diplomacy.

Samoa itself favored federated lineages and councils, emphasizing balance and shared titles rather than centralized kingship. -

The Society and Marquesas Islands flourished with dense populations and fortified valleys governed by hereditary aristocracies.

-

In East Polynesia, Rapa Nui consolidated into competing lineages (mata), each raising monumental ahu platforms and carving moai statues that embodied deified ancestors.

Pitcairn and Henderson, linked to Mangareva, maintained smaller horticultural and voyaging communities.

Across the ocean, these societies varied in scale but shared a common template: divine chiefs, ritual centers, and community labor harnessed to sustain abundance and hierarchy.

Economy and Exchange

Agricultural and maritime economies underpinned prosperity.

-

Taro pondfields (loʻi) and dryland sweet potatoes (‘uala) provided staples in Hawaiʻi and the western islands.

-

Yams, breadfruit, coconuts, bananas, and fishpond aquaculture diversified food sources.

-

Inter-island exchange conveyed tapa cloth, mats, feathers, canoes, and basalt adzes, while tribute networks redistributed wealth across Tonga’s sphere.

-

In the east, Rapa Nui relied on sweet potatoes, chickens, and marine resources, while Pitcairn exported basalt and imported crops via voyaging partners.

Fishing, reef gathering, and aquaculture sustained protein supply, while long-distance voyaging exchanged both goods and genealogies—the currency of alliance and prestige.

Technology and Craft

Innovation rested on the twin arts of agriculture and navigation.

Double-hulled voyaging canoes (waʻa kaulua) traversed hundreds of miles with sails and paddles, guided by stellar constellations, swells, and bird flight.

Stone adzes, coral and bone fishhooks, woven nets, and wooden digging sticks equipped daily labor.

Barkcloth textiles and fine mats carried both practical and ceremonial value.

Monumental architecture—marae in the Society Islands, heiau in Hawaiʻi, and ahu in Rapa Nui—expressed cosmological alignment and chiefly prestige, their construction itself a ritual of social cohesion.

Belief and Symbolism

Religion bound society through reverence for ancestors, gods, and mana.

Polynesians perceived no separation between nature and spirit: mountains, stones, trees, and ocean currents all bore divine essence.

Chiefs embodied the living bridge between gods and people; their sanctity was protected by kapu, or ritual restriction.

Temples hosted ceremonies for fertility, warfare, and voyaging; priests interpreted omens, winds, and tides.

Across islands, myths of creation, navigation, and heroic ancestry unified the Pacific imagination—the sea itself a sacred text of origin and return.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Voyaging remained vigorous within each archipelago and across adjacent groups.

-

The Tongan network linked Samoa, Fiji, and the Cook Islands.

-

Hawaiian navigators sailed between the main islands and northward to the Northwestern Hawaiian chain, including Midway.

-

Society–Marquesas routes bound French Polynesia into cultural unity, while Mangareva–Pitcairn–Rapa Nui formed the easternmost exchange circuit.

Atolls served as maritime crossroads, their people skilled intermediaries who balanced scarcity with seaborne exchange.

Although trans-Pacific voyages beyond Polynesia declined after earlier centuries, regional connectivity remained strong, knitting the islands into one oceanic system.

Adaptation and Resilience

Resilience stemmed from ecological intelligence and social organization.

Agricultural intensification—especially pondfield irrigation and arboriculture—stabilized food supply; fishponds and reef management buffered lean years.

Kinship and ritual enforced redistribution during famine or cyclone.

On marginal islands and atolls, mobility replaced permanence: households shifted between resource zones, and long-distance ties ensured mutual aid.

The voyaging canoe, both tool and symbol, embodied this resilience—capable of linking ecosystems and societies across thousands of miles.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251 CE, Polynesia stood as a constellation of advanced chiefdoms unified by culture and sea.

-

In Hawaiʻi, complex stratification and temple construction foreshadowed future kingdoms.

-

In Tonga, imperial networks extended across the western Pacific.

-

In Samoa and French Polynesia, federated aristocracies balanced power through ritual and lineage.

-

On Rapa Nui, monumental ancestor cults reached unprecedented artistic and spiritual expression.

Across the ocean, voyaging, agriculture, and faith combined to create one of the most integrated non-literate civilizations on Earth—a world of sacred landscapes and navigated horizons that anticipated the political unifications and monumental achievements of later centuries.