Southwest Europe (964 – 1107 CE): Taifa …

Years: 964 - 1107

Southwest Europe (964 – 1107 CE): Taifa Courts, Norman Kings, and the Pilgrim Atlantic

Geographic and Environmental Context

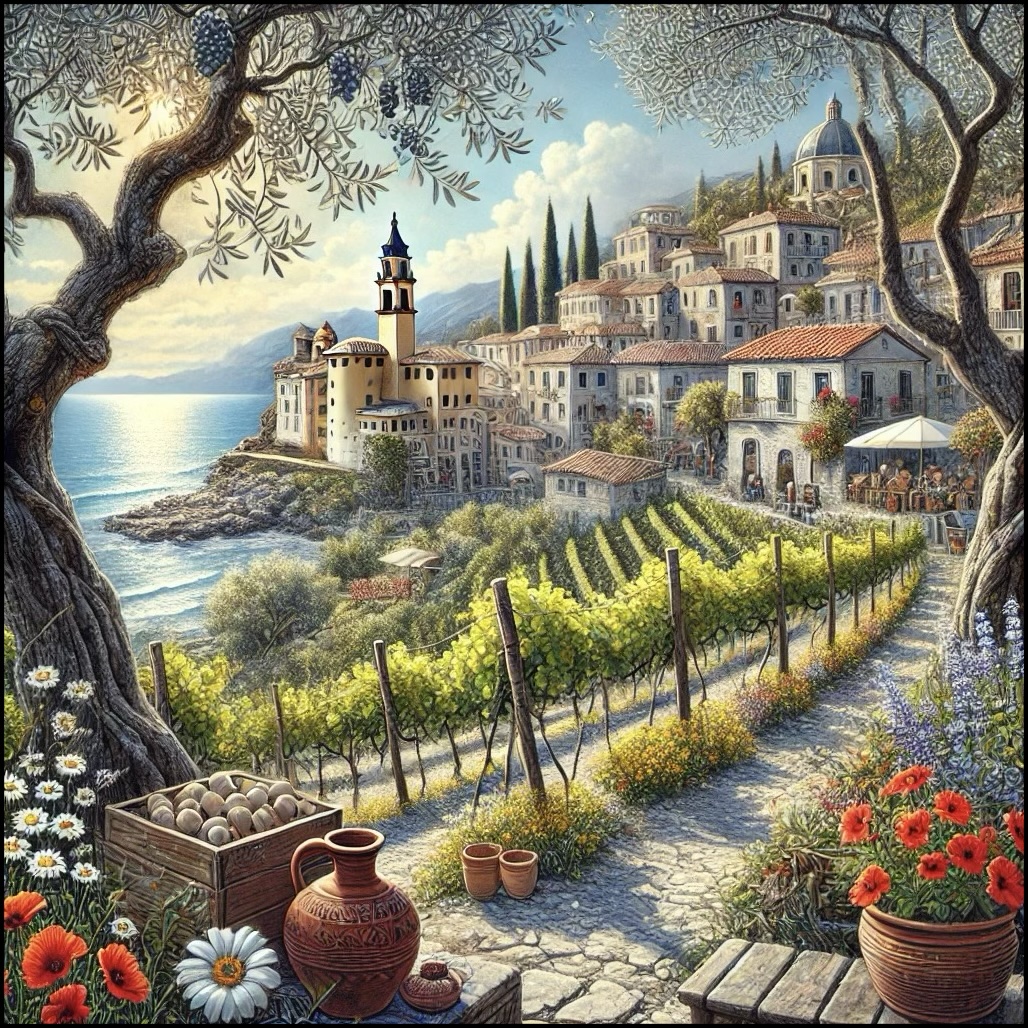

Southwest Europe extended from the Atlantic coasts of Portugal and northern Spain to the Mediterranean heartlands of al-Andalus, Italy, and the islands of the western sea.

It encompassed the Andalusian taifas, the Castilian and Leonese uplands, the Ebro corridor and Catalan march, the Balearic Islands, Sicily, Sardinia, Malta, and the Italian peninsula from Venice to Apulia.

Mountain chains—the Cantabrian range, Sierra Morena, and Apennines—divided temperate valleys and coastal plains.

Key nodes included Seville, Toledo, Valencia, Lisbon, León, Santiago de Compostela, Venice, Pisa, Genoa, Palermo, and Naples, each connected by maritime and overland arteries binding the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Adriatic.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950–1250) sustained stable warmth and generous rainfall.

-

Vineyards and olive groves thrived from Andalusia to Tuscany.

-

Andalusian irrigation and Italian terraces increased yields, supporting large urban populations.

-

In Atlantic Iberia, fertile valleys of the Minho, Douro, and Tagus produced wheat, vines, and chestnuts.

-

Seasonal winds—the monsoon-like summer westerlies and Mediterranean sea breezes—facilitated shipping from the Straits of Gibraltar to the Levant.

Societies and Political Developments

Al-Andalus and the Christian Frontier

After the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate (1031), al-Andalus fragmented into taifa kingdoms—Seville, Zaragoza, Valencia, and Granada—each vying for tribute and prestige.

These cities flourished as centers of learning, architecture, and luxury production, until threatened by the northern Christian monarchies.

In 1086, the Almoravids, invited from North Africa, restored unity briefly, defeating Castile at Sagrajas.

To the north, León, Castile, Aragon, Navarre, and Catalonia advanced the Reconquista, seizing Toledo (1085) and pressing southward.

Lisbon, under the taifa of Badajoz, remained a major Muslim entrepôt linking the Atlantic and the caliphal interior.

The Leónese and Atlantic Heartlands

In the west, the Kingdom of León dominated the 10th–11th centuries.

-

Under Ordoño III, Ferdinand I, and Alfonso VI, León extended from Galicia to the Tagus.

-

Castile, born as a marcher county, evolved into a frontier kingdom famed for its castles and independent spirit.

-

Galicia, integrated under León, revolved around Santiago de Compostela, where the pilgrimage cult of St. James transformed the region into a magnet for European devotion.

-

In Portugal, the marches of Portucale and Coimbra revived after 1064, with Porto and Braga emerging as Atlantic trade ports.

Italy and the Central Mediterranean

While Iberia was a land of religious frontier, Italy was a sea of republics.

-

In the north, Venice, Genoa, and Pisa matured into maritime communes, pioneering republican institutions, notarial law, and crusade logistics.

-

In the south, Normans, led by Robert Guiscard and Roger I, conquered Sicily (1061–1091) and Malta, creating a tri-lingual kingdom blending Latin, Greek, and Arabic.

-

Sardinia’s judicati balanced Pisan and Genoese influence, while Naples and Apulia formed the Norman–papal frontier.

-

Venice, ruling the Adriatic, became the central broker between Byzantine, Levantine, and western markets.

Economy and Trade

Southwest Europe’s prosperity rested on an intricate web of agriculture, craftsmanship, and maritime exchange.

-

Andalusian taifas exported textiles, ceramics, sugar, citrus, and leather, while importing Christian slaves, timber, and metals.

-

León and Castile traded grain, wine, wool, and hides through Burgos, Porto, and Santiago’s ports.

-

Lisbon re-exported Andalusi goods northward to Aquitaine and Brittany.

-

Venice, Genoa, and Pisa dominated shipping lanes to the Levant and Egypt, pioneering lateen-rigged galleysand merchant convoys.

-

Sicilian plantations under the Normans expanded sugar and citrus exports.

-

Italian banking and credit instruments emerged in urban markets by the century’s end.

Together, these routes transformed the western Mediterranean and Atlantic into a continuous commercial zone.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Andalusian irrigation systems (qanāts, norias, and acequias) sustained dense farming and gardens.

-

Romanesque architecture and Moorish stucco carving flourished side by side across Iberia.

-

Italian shipyards standardized hulls and rigging; urban notaries codified contracts and loans.

-

Water-mills and terraced vineyards multiplied in Galicia, León, and northern Portugal, improving rural productivity.

-

Artisanal specialization in glass, metalwork, and ceramics distinguished Córdoba, Valencia, Venice, and Amalfi.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Ebro–Tagus–Guadalquivir trunks tied the interior taifas to Mediterranean ports.

-

Camino de Santiago, the great pilgrim road, linked Aquitaine and Navarre to Compostela, stimulating monasteries, inns, and markets.

-

Pyrenean passes (Somport, Roncesvalles) joined Aragon and Catalonia to France and Andorra.

-

Adriatic sea-lanes radiated from Venice; Tyrrhenian circuits connected Sardinia, Sicily, Naples, and Rome.

-

Atlantic sea routes bound Porto, Braga, and Lisbon to Bordeaux, Bayonne, and Brittany, forming a “pilgrim sea” complementing the overland Camino.

Belief and Symbolism

Religious diversity defined the region’s identity.

-

Iberia blended Islamic, Mozarabic, and Latin traditions—mosques and Romanesque churches coexisted in frontier towns.

-

Cluniac reform reached León, Castile, and Catalonia, renewing monastic discipline and pilgrimage infrastructure.

-

Santiago de Compostela became Europe’s third great shrine, after Rome and Jerusalem, symbolizing Christendom’s advance into the western frontier.

-

In Norman Sicily, Arabic artisans, Greek clerics, and Latin knights cooperated under royal patronage; the Palatine Chapel embodied this syncretic trilingual culture.

-

Venetian crusading ideology merged faith and commerce, anticipating the maritime crusades of the 12th century.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Frontier colonization repopulated Duero and Tagus valleys with mixed Mozarabic, Basque, and Frankish settlers.

-

Pilgrimage economies stabilized infrastructure through shared spiritual and material investment.

-

Norman administration in Sicily integrated Arabic fiscal systems and Greek bureaucracy with Latin law.

-

Italian communes institutionalized civic cooperation, fortifying autonomy amid imperial–papal conflict.

-

Maritime republics diversified routes, ensuring continuity of trade even through warfare or piracy.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, Southwest Europe had become one of the most dynamic crossroads of the medieval world:

-

Venice, Genoa, and Pisa commanded the seas, laying foundations for Europe’s commercial expansion.

-

Norman Sicily stood as a Mediterranean hinge, fusing Christian, Muslim, and Byzantine traditions.

-

Taifa Spain dazzled with artistry even as it faced Almoravid unification.

-

León, Castile, and Portugal pushed southward in a Reconquista that paralleled pilgrimage prosperity and frontier growth.

-

The Camino de Santiago and pilgrim Atlantic bound Christendom together in faith and movement, while Islamic, Christian, and Jewish exchanges enriched its culture.

This was an age of urban rebirth, seaborne power, and spiritual mobility—a world where ports, palaces, and pilgrim roads alike radiated the vitality of a newly interconnected Southwest Europe.

Mediterranean Southwest Europe (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

People

Groups

- Berber people (also called Amazigh people or Imazighen, "free men", singular Amazigh)

- Jews

- Moors

- Islam

- al-Andalus (Andalusia), Muslim-ruled

- Al-Garb Al-Andalus

- Mozarabs

- Venice, Duchy of

- Papal States (Republic of St. Peter)

- Aragón, or Zaca, County of

- Barcelona, County of

- Malta

- Sicily, Emirate of

- Logudoro, Giudicato of

- Arborea, Giudicato of

- Córdoba, (Umayyad) Caliphate of

- Ifriqiya, Fatimid Caliphate of

- Kalbids

- Normans

- Amalfi, Duchy of

- Holy Roman Empire

- Italy, Kingdom of (Holy Roman Empire)

- Gallura, Giudicato of

- Castillian people

- Italy, Catepanate of

- Castile, County of

- Ifriqiyah, Zirid Dynasty of

- Pisa, (first) Republic of

- Genoa, (Most Serene) Republic of

- Badajoz, Taifa of

- Almería, Muslim statelet, or taifa, of

- Denia, Muslim statelet, or taifa, of

- Valencia, Muslim statelet, or taifa, of

- Toledo, (Muslim statelet, or taifa, of)

- Granada, (Zirid) Muslim statelet, or taifa, of

- Zaragoza, Muslim statelet, or taifa, of

- Cagliari, Giudicato of

- Sevilla, (Abbadid) Muslim statelet, or taifa, of

- Castile, Kingdom of

- Aragón, Kingdom of

- Ifriqiyah, Zirid Dynasty of

- Christians, Roman Catholic

- Capua, Norman Principality of

- Apulia, Norman Duchy of

- Almoravid dynasty

- Arborea, Giudicato of

- Sicily, County of

- Amalfi, Duchy of

- Valencia, Muslim statelet, or taifa, of

- Apulia, Norman Duchy of

- Castile, Kingdom of

- Aragón, Kingdom of

Topics

- Reconquista, the

- Medieval Warm Period (MWP) or Medieval Climate Optimum

- al-Andalus, Fitna of

- Norman Conquest of Southern Italy

- Crusade, First

- Crusades, The

Commodoties

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Sweeteners

- Beer, wine, and spirits