King Henry, reaffirming the Treaty of Nemours …

Years: 1588 - 1588

September

King Henry, reaffirming the Treaty of Nemours in August 1588, had recognized Cardinal de Bourbon as heir, and made the duc de Guise Lieutenant-General of France.

Refusing to return to Paris, Henry calls in September of this year for an Estates-General at Blois.

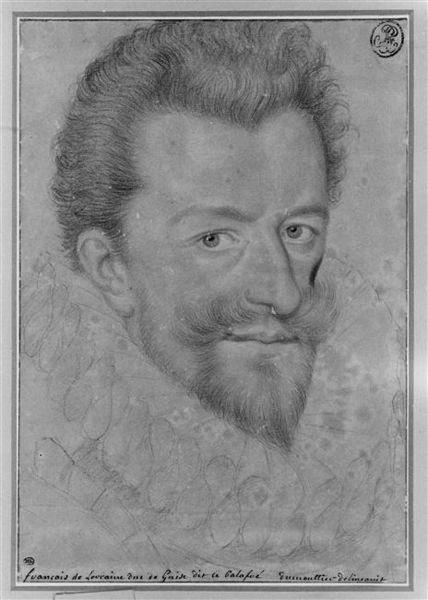

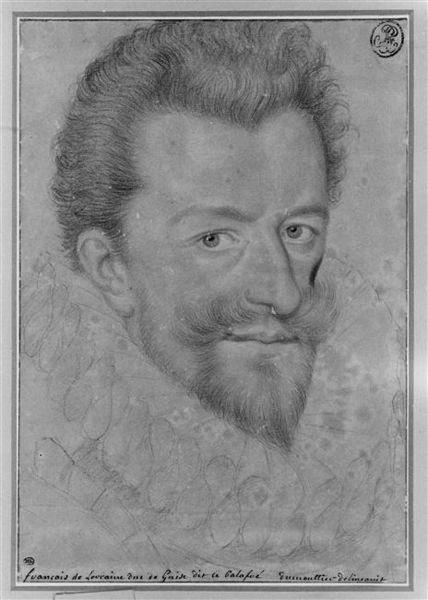

Unknown artist: Henry I, Duke of Guise, Louvre, Paris

Locations

People

Groups

- Papal States (Republic of St. Peter)

- Lorraine, (second) Duchy of

- France, (Valois) Kingdom of

- England, (Tudor) Kingdom of

- Navarre, Lower, Kingdom of

- Huguenots (the “Reformed”)

- Spain, Habsburg Kingdom of

- Holy, or Catholic, League, the (French)

Topics

- Counter-Reformation (also Catholic Reformation or Catholic Revival)

- Religion, Eighth War of (War of the Three Henrys)

- Spanish Armada, Defeat of the

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 34560 total

All of Japan is controlled by the dictatorial Hideyoshi either directly or through his sworn vassals, and a new national government structure has evolved: a country unified under one daimyo alliance but still decentralized.

The basis of the power structure is again the distribution of territory.

A new unit of land measurement and assessment—the koku—is instituted.

One koku is equivalent to about one hundred and eighty liters of rice; daimyo are by definition those who hold lands capable of producing ten thousand koku or more of rice.

Hideyoshi personally controls two million of the eighteen and a half million koku total national assessment (taken in 1598).

Tokugawa Ieyasu, a powerful central Honshu daimyo (not completely under Hideyoshi's control), holds two and a half milllion million koku.

Despite Hideyoshi's tremendous strength and the fear in which he is held, his position is far from secure.

He attempts to rearrange the daimyo holdings to his advantage, for example, reassigning the Tokugawa family to the conquered Kanto region and surrounding their new territory with more trusted vassals.

He also adopts a hostage system for daimyo wives and heirs at his castle town at Osaka and uses marriage alliances to enforce feudal bonds.

He imposes the koku system and land surveys to reassess the entire nation.

In 1590 Hideyoshi declares an end to any further class mobility or change in social status, reinforcing the class distinctions between cultivators and bushi (only the latter can bear arms).

He provides for an orderly succession in 1591 by taking the title taiko, or retired kanpaku, turning the regency over to his son Hideyori.

Only toward the end of his life does Hideyoshi try to formalize the balance of power by establishing the five-member Board of Regents (one of them Ieyasu), sworn to keep peace and support the Toyotomi, the five-member Board of House Administrators for routine policy and administrative matters, and the three-member Board of Mediators, who are charged with keeping peace between the first two boards.

Hideyoshi's major ambition is to conquer China, and in 1592, with an army of two hundred thousand troops, he invades Korea, at this time a Chinese vassal state.

His armies quickly overrun the peninsula before losing momentum in the face of a combined Korean-Chinese force.

During peace talks Hideyoshi demands a division of Korea, free-trade status, and a Chinese princess as consort for the emperor.

The equality with China sought by Japan is rebuffed by the Chinese and peace efforts end.

In 1597 a second invasion is begun, but it abruptly ends with Hideyoshi's death in 1598.

Hideyoshi in 1577 had seized Nagasaki, Japan's major point of contact with the outside world.

He had taken control of the various trade associations and has tried to regulate all overseas activities.

Although China rebuffs his efforts to secure trade concessions, Hideyoshi succeeds in sending commercial missions to the Philippines, Malaya, and Siam (present-day Thailand).

He is suspicious of Christianity, however, as potentially subversive to daimyo loyalties and he has some missionaries crucified.

Korea suffers devastating foreign invasions at the end of the sixteenth century.

The first comes shortly after Toyotomi Hideyoshi ends Japan's internal disorder and unifies the islands.

His eventual goal is to put China under his control, and he launches an invasion that puts some one hundred and sixty thousand Japanese soldiers at Pusan in 1592.

At this, the Joseon court takes flight to the Yalu River, infuriating ordinary Koreans and leading slaves to revolt and burn the registries.

Japanese forces march through the peninsula at will.

In the nick of time, however, Korean admiral Yi Sun-sin builds the world's first armor-clad ships, so-called "turtle ships" encased in thick plating with cannons sticking out at every point on their circular shape, which destroy Japanese fleets wherever they are found.

The Korean ships cut Japan's supply routes, and, combined with the dispatch of Ming forces and so-called "righteous armies" that rise up in guerrilla warfare (even Buddhist monks participate), cause the Japanese to retreat to a narrow redoubt near Pusan.

Hideyoshi, after desultory negotiations and delay, launches a second invasion in 1597.

This time, the Korean and Ming armies are ready.

Yi Sun-sin, with a mere dozen warships, demolishes the Japanese forces in Yellow Sea battles near the port of Mokp'o.

The would-be conqueror Hideyoshi dies, and Japanese forces withdraw to their home islands where they will nurse an isolationist policy for the next two hundred and fifty years.

In spite of the Joseon victory, the peninsula has been devastated.

Refugees wander its length, famine and disease are rampant, and even the basic land relationships are overturned by the widespread destruction of the registers.

Korea has paid a terrible price for turning back invasions that otherwise would have substantially redirected East Asian history.

East Europe (1588–1599 CE): Muscovite Stability and Administrative Reforms

Political and Military Developments

Consolidation of Central Authority

From 1588 to 1599 CE, Muscovy further consolidated central authority, stabilizing governance following previous decades of turmoil. Tsar Feodor I’s reign, guided significantly by his regent Boris Godunov, saw strengthened administrative reforms aimed at enhancing political stability and efficiency.

Continued Territorial Integration

The integration and administration of diverse territories, particularly those involving ethnic groups such as the Bashkirs and other Ural and Volga populations, remained a priority. Diplomatic engagements and military presence ensured relative peace and administrative coherence across these regions.

Economic and Technological Developments

Sustained Economic Revival

Economic growth continued steadily, bolstered by robust trade along vital routes such as the Volga River and international commerce. Urban centers, notably Moscow, benefited from improved trade conditions and economic resilience.

Technological and Military Advancements

Military enhancements persisted, focusing on fortification improvements, refined siege tactics, and advancements in cavalry operations. These developments significantly bolstered Muscovy’s defensive capabilities and regional stability.

Cultural and Artistic Developments

Flourishing Cultural Patronage

Cultural and artistic patronage continued under Tsar Feodor I, facilitating the growth of architectural projects, religious artwork, and secular cultural initiatives. These activities contributed significantly to the Muscovite cultural identity and heritage.

Vibrant Intellectual Environment

Intellectual and literary productivity flourished, with chroniclers and scholars actively recording and analyzing the political, religious, and social developments. This scholarly activity maintained historical continuity and enriched Muscovy’s intellectual heritage.

Settlement Patterns and Urban Development

Urban Expansion and Development

Cities, particularly Moscow, expanded further, supported by strategic infrastructure investments, efficient urban planning, and enhanced administrative oversight. Population growth and economic vitality characterized this urban expansion.

Strengthened Fortifications and Regional Defense

Improvements in urban fortifications continued, ensuring security and stability amid ongoing regional management challenges and geopolitical dynamics.

Social and Religious Developments

Enhanced Social Stability

Social structures stabilized further, integrating diverse ethnic groups into cohesive administrative and societal frameworks. The continued incorporation of ethnic territories enhanced regional harmony and administrative efficiency.

Orthodox Church’s Continuing Influence

The Orthodox Church remained a central societal institution, guiding educational norms, moral values, and community cohesion, thus significantly contributing to overall societal stability and cultural continuity.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The era from 1588 to 1599 CE represented continued administrative consolidation, economic growth, and cultural enrichment. These developments reinforced Muscovy’s central governance and territorial integration, setting essential foundations for future stability and state cohesion.

Northeast Europe (1588–1599 CE): Post-War Stabilization, Continued Rivalries, and Cultural Flourishing

Between 1588 and 1599 CE, Northeast Europe transitioned from prolonged warfare to relative stabilization following the conclusion of the Livonian War. This period saw cautious diplomatic realignments, internal political consolidations, continued economic resilience, and significant cultural and intellectual developments, even as regional rivalries persisted.

Aftermath and Stabilization Following the Livonian War

The Treaty of Plussa (1583) and the Truce of Yam-Zapolsky (1582) ended hostilities, allowing Northeast Europe a brief respite from decades of warfare. Territories previously ravaged by conflict, especially in Livonia, began recovery processes through reconstruction and economic revitalization, although geopolitical tensions remained high among former combatants.

Swedish Consolidation and Governance in Estonia and Livonia

Under John III (r. until 1592) and subsequently his son Sigismund III Vasa, Sweden solidified its control over northern Livonia and Estonia. Sweden improved administrative governance, reinforced defensive fortifications in key cities such as Reval (Tallinn) and Narva, and encouraged continued settlement by communities like the Forest Finns, enhancing Sweden’s territorial stability and economic strength.

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth’s Internal Strength and Regional Influence

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth under Sigismund III Vasa (r. from 1587) sought internal stability and consolidation of its extensive Livonian territories. The Commonwealth maintained effective administrative control, promoted economic recovery, and strengthened diplomatic relationships, solidifying its role as a central power influencing Northeast Europe’s geopolitical landscape.

Denmark–Norway’s Maritime and Diplomatic Ambitions

Under Christian IV (r. from 1588), Denmark–Norway actively strengthened its Baltic maritime interests. The kingdom invested in naval expansion, enhanced fortifications, and diplomatic initiatives aimed at balancing Swedish and Polish–Lithuanian influence, further complicating regional dynamics.

Muscovy’s Internal Challenges and Territorial Adjustments

Following the death of Ivan IV (the Terrible) in 1584 and the subsequent ascension of Feodor I, Muscovy grappled with significant internal governance challenges. Despite diplomatic truces, Muscovy continued strategic preparations aimed at future territorial revisions, maintaining regional tension.

Economic Stability and Growth in the Duchy of Prussia

Under Duke Albert Frederick, the secularized Duchy of Prussia sustained political neutrality, robust internal governance, and continued economic prosperity, particularly through thriving urban centers like Königsberg. Prussia’s strategic diplomatic neutrality and economic strength provided regional stability amidst surrounding geopolitical shifts.

Continued Economic Vitality of Urban Centers

Major urban centers such as Reval (Tallinn), Riga, Königsberg, and Visby on Gotland furthered their economic resilience. Stable maritime commerce, active merchant networks, and effective urban governance fostered regional prosperity and helped recover from the war’s disruptions.

Cultural, Educational, and Religious Flourishing

Protestantism, especially Lutheranism, deepened its influence, driving further educational reforms and cultural developments. Schools and universities flourished, promoting literacy, intellectual advancements, and cultural production across Northeast Europe. However, religious tensions, particularly between Protestant and Catholic communities, continued to influence internal and external politics significantly.

Intellectual and Scientific Contributions

The region continued to benefit from intellectual advancements, exemplified by the continuing impact of Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, whose meticulous astronomical observations remained influential, setting the stage for future scientific developments and consolidating Northeast Europe as a significant center of scholarly activity.

Diplomatic Realignments and Strategic Maneuvering

Diplomatic interactions remained intricate as regional powers navigated post-war realities. Negotiations and alliances sought to balance territorial interests, mitigate ongoing rivalries, and secure lasting stability, reflecting continued geopolitical caution among major powers.

Legacy of the Era

The era from 1588 to 1599 CE significantly shaped Northeast Europe's trajectory through post-war stabilization, cultural advancements, and continued diplomatic complexity. These developments laid critical foundations for subsequent regional stability, territorial delineations, and cultural identities, guiding Northeast Europe into the seventeenth century.

The origin of the Forest Finns lies in the Swedish colonization policy in Finland, a part of the Swedish Empire since the thirteenth century.

The powers to the east of Finland, Novgorod and later Russia, have constantly challenged the Swedish sovereignty of the often sparsely populated provinces of Eastern Finland.

To secure their realm, the Swedish kings, notably Gustav Vasa (r. 1528-60) and Eric XIV (r. 1561-8), have encouraged farmers to settle these vast wilderness regions, which in turn are used to the traditional slash-and-burn agriculture.

These settlements face several problems, from conflicts with the original populations of Sami people and Karelians to harsh conditions living in frontier lands during war times.

The fact that slash-and-burn itself requires a relatively low human population density or a continuing supply of new "frontier" lands, also causes overpopulation and by the late sixteenth century forces migration by Forest Finns from Savonia and Häme (Swedish: Tavastland).

The main part moves north to Ostrobothnia (Österbotten) and Kainuu (Kajanaland), east towards northern Karelia (Karelen), and south towards Ingria (Swedish land at that time, now part of Russia).

However, an estimated ten to fifteen percent cross the Baltic Sea in search of largely uninhabited lands suitable for their needs.

The first Forest Finn settlements in Sweden proper are established in Norrland, in the provinces of Gästrikland, Ångermanland and Hälsingland in the 1580s and 90s.

Years: 1588 - 1588

September

Unknown artist: Henry I, Duke of Guise, Louvre, Paris

Locations

People

Groups

- Papal States (Republic of St. Peter)

- Lorraine, (second) Duchy of

- France, (Valois) Kingdom of

- England, (Tudor) Kingdom of

- Navarre, Lower, Kingdom of

- Huguenots (the “Reformed”)

- Spain, Habsburg Kingdom of

- Holy, or Catholic, League, the (French)

Topics

- Counter-Reformation (also Catholic Reformation or Catholic Revival)

- Religion, Eighth War of (War of the Three Henrys)

- Spanish Armada, Defeat of the