King Fan Hu Ta of Champa, seeing …

Years: 400 - 411

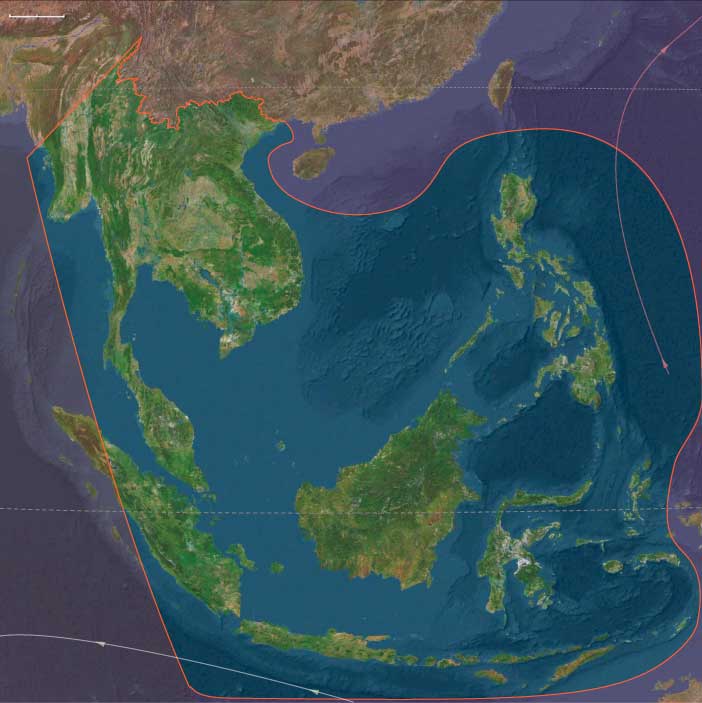

King Fan Hu Ta of Champa, seeing an opportunity amid the instability of China’s deteriorating Jin dynasty, conducts raids from Hue in 405 and 407 on the Chinese-controlled Nam Viet territory to the north.

Locations

People

Groups

- Vietnamese people

- Cham people

- Chinese (Han) people

- Lam-Ap, or Lin-yi, (Cham) Kingdom of

- Chinese Empire, Tung (Eastern) Jin Dynasty

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 59279 total

Tao Yuanming, an influential Chinese nature poet, had served more than ten years in government service, personally involved with the sordid political scene of the times.

He had served in both civil and military capacities, which included making several trips down the Yangzi to the capital Jiankang, at this time a thriving metropolis, and the center of power during the Six Dynasties; the ruins of the old Jiangkang walls can still be found in the modern municipal region of Nanjing.

During this period of service in a series of minor posts, Tao Yuanming's poems had begun to indicate that he was becoming torn between ambition and a desire to retreat into solitude.

Tao Yuanming in the spring of 405 is serving in the army, as aide-de-camp to the local commanding officer.

The death of his sister, together with his disgust at the corruption and infighting of the Jin Court, prompts him to resign, factors that have led to his becoming convinced that life is too short to compromise on his principles.

He serves briefly as a magistrate in Pengze, but resigns after a tenure of only eighty-three days and returns to his farm to pursue a life of freedom and frugality.

His poetical insight stemming from the Taoist principle of oneness with nature, he produces poems characterized by simple diction and a spontaneous feel.

An artful prose writer, he portrays a utopian world according to the Taoist ideal in The Peach-blossom Spring, and produces an engaging self-portrait in his Biography of Master Five Willows.

The name Peach Blossom Spring (Tao Hua Yuan) has since become the standard Chinese term for 'utopia'.

Approximately one hundred and thirty of his works survive: mostly poems or essays which depict an idyllic pastoral life of farming and drinking.

His poems will inspire not only generations of poets, but also painters and other artists.

Japan starts to send tribute to Imperial China in the fifth century.

In the Chinese historical records, the polity is called Wa, and its five kings are recorded.

Based upon the Chinese model, the Japanese rulers develop a central administration and an imperial court system, organizing society into various occupation groups.

The Decline of the Roman Empire

By the late fourth and early fifth centuries, the Roman Empire stands in a state of terminal decline. The division of the empire into eastern and western halves in 395 CE—formalized upon the death of Theodosius I—has only deepened internal political strife, weakening Rome’s ability to resist barbarian incursions along the Danube and even into Italy itself.

The Strength of the East vs. the Weakness of the West

While Germanic tribes break through into the Balkans, they fail to establish permanent settlements there. The Eastern Roman emperors, prioritizing the defense of Constantinople, actively push these tribes westward, forcing them deeper into the Western Empire and exacerbating instability.

Despite political challenges, the Eastern Empire maintains relative stability and prosperity. Constantinople, benefiting from its Greek cultural heritage, emerges as the dominant symbol of civilization in the East. For much of its population—already accustomed to Greek language and traditions—the shift from a Latin Roman Empire to a more Hellenized Byzantine identity is seamless.

By contrast, the Western Empire is crumbling. Repeated barbarian invasions, coupled with rural depopulation, have crippled its economy and defenses. By 400 CE, many tenant farmers have been reduced to a serf-like status, bound to the land by economic necessity and social rigidity. Meanwhile, the Eastern Empire, benefiting from lucrative trade in spices, silk, and luxury goods, remains wealthy and resilient.

The Germanization of Rome

The progressive Germanization of the empire, particularly within the Roman army, is nearly complete. The Goths, like most Germanic tribes—with the notable exception of the Franks and Lombards—have converted to Arian Christianity, a doctrine the Catholic (Orthodox) Romans regard as dangerous heresy.

However, the Roman senatorial aristocracy, largely pacifist and still clinging to its classical traditions, views the warlike Germanic customs with suspicion and hostility. This growing resentment against Germanic leaders in high office fuels political instability in both the Eastern and Western Empires, leading to factionalism and periodic violence.

Yet, despite the tensions, Rome relies on Germanic tribes to defend its imperial frontiers. The Franks, for instance, are settled in Toxandria (modern Brabant) and tasked with guarding the empire’s northern borders—a foreshadowing of their future role as rulers of post-Roman Gaul.

The Weakness of the Western Emperor

The reigning Western Roman emperor, an inexperienced and feeble ruler, has inherited the throne from his father but lacks military expertise. His shortsighted political interventions and inability to command armies only deepen the empire’s crises, as generals struggle to hold the frontiers against an unrelenting tide of barbarian invasions.

Fearing a direct assault on Rome, he relocates the imperial court from Rome to Ravenna, a more defensible stronghold surrounded by marshlands and the sea. From his new capital, he watches as loyal generals suppress usurpers and internal revolts, rather than leading the defense himself.

Meanwhile, the Rhine frontier deteriorates, and the administrative center of Gaul is moved from Trier to Arelate(modern Arles), leaving the northern provinces increasingly vulnerable to Germanic incursions. The combination of military neglect, civil war, and external invasions accelerates the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, setting the stage for the fall of Rome itself in 476 CE.

East Central Europe (400–411 CE): Hunnic Dominance, Roman Frontier Erosion, and Tribal Realignments

Between 400 and 411 CE, East Central Europe—covering Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, and those portions of Germany and Austria lying east of 10°E and north of a line stretching from roughly 48.2°N at 10°E southeastward to the Austro-Slovenian border near 46.7°N, 15.4°E—faced accelerating geopolitical changes driven primarily by increasing Hunnic power under leaders such as Uldin. The Roman Danube frontier, already weakened, suffered further erosion as the Huns solidified control over vast regions. Nevertheless, established tribal communities, particularly the Rugii, maintained stability, adapting diplomatically to shifting power dynamics. Simultaneously, proto-Slavic communities continued their resilience amid regional turbulence.

Political and Military Developments

Hunnic Ascendancy and Regional Control

-

Hunnic dominance in East Central Europe intensified significantly during this era, as Huns under leaders like Uldin exerted growing political and military influence over neighboring tribes, reshaping local power structures.

-

The Huns directly pressured Roman frontier provinces (Pannonia Prima, Secunda, Savia, and Valeria), effectively undermining Roman authority and control along the Danube frontier.

Further Roman Frontier Weakness

-

Roman provinces along the Danube struggled to maintain their territorial integrity and military defenses in the face of relentless Hunnic threats. Resources were overstretched, resulting in weakened provincial governance and diminished security.

Continued Rugian Stability

-

The Rugii, established securely along the upper Tisza River in Roman-controlled Pannonia, adeptly navigated regional politics, maintaining their settlements and diplomatic ties with Roman authorities, Goths, and increasingly the Huns.

Economic and Technological Developments

Economic Disruption and Local Adaptation

-

The spread of Hunnic power caused disruptions to regional trade networks, particularly affecting Roman-controlled areas. Nonetheless, localized economic exchanges between tribal groups and Roman settlements continued, albeit cautiously.

Frontier Fortification Efforts

-

Despite limited resources, Roman authorities continued maintenance and limited reinforcement of essential frontier infrastructure, primarily defensive fortifications and communication routes critical for frontier security.

Cultural and Artistic Developments

Increased Cultural Hybridization

-

The Hunnic presence significantly influenced regional material culture, blending local Germanic and Roman artistic styles with Hunnic motifs. Practical and portable items such as weaponry, jewelry, and decorative metalwork increasingly reflected these hybrid aesthetics.

Proto-Slavic Cultural Continuity

-

Proto-Slavic communities sustained traditional cultural and social structures, demonstrating remarkable resilience amid shifting regional power dynamics and increased Hunnic influence.

Settlement and Urban Development

Strained Frontier Towns

-

Roman frontier settlements (Carnuntum, Vindobona, Aquincum) faced increased economic hardship and demographic decline. They persisted primarily as fortified military outposts responding to escalating threats.

Rugian Settlements as Centers of Stability

-

Rugian communities near the upper Tisza continued their relative prosperity, serving as regional centers of stability and maintaining economic vitality through strategic diplomatic interactions.

Social and Religious Developments

Adaptation of Tribal Leadership

-

Rugian tribal leadership effectively managed internal cohesion and external diplomacy, negotiating successfully with Romans, Goths, and the expanding Hun hegemony, thus preserving their autonomy and regional importance.

Proto-Slavic Social Resilience

-

Proto-Slavic populations maintained stable social hierarchies and religious practices, reinforcing community cohesion despite growing external threats and pressures.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The era 400–411 CE represented a critical phase of intensified Hunnic dominance and the further erosion of Roman frontier authority in East Central Europe. The adept diplomatic adaptations of tribal communities, particularly the Rugii, and the enduring cultural resilience of proto-Slavic populations, highlighted regional capacity for adaptation. These transformations significantly reshaped local power dynamics and cultural landscapes, setting the stage for more dramatic migrations and geopolitical changes in the decades that followed.

Eastern Southeast Europe (400–411 CE): Increasing Migrations and Defensive Adjustments

Settlement and Migration Patterns

Intensified Barbarian Migrations

Between 400 and 411 CE, Eastern Southeast Europe witnessed significant migrations and invasions from groups such as the Visigoths, Ostrogoths, and Huns. These movements intensified pressures along the Roman Empire's borders, leading to growing settlements within the region and affecting urban and rural demographics.

Strengthened Urban Fortifications

Cities like Constantinople, Thessalonica, and Philippopolis further strengthened defensive infrastructure in response to increased external threats. Enhanced walls, fortresses, and military installations reflected adaptive responses to migration pressures.

Economic and Technological Developments

Economic Disruptions and Adaptations

Despite challenges posed by invasions, economic activity in the region remained resilient. Agricultural production, urban commerce, and trade continued, albeit with disruptions and adaptations to changing security and logistical conditions.

Military Technology and Infrastructure

Technological and infrastructural enhancements increasingly focused on defensive needs, including improved fortifications, weaponry, and military logistics. These developments ensured sustained military readiness and economic continuity in the face of mounting pressures.

Cultural and Artistic Developments

Cultural Resilience

Cultural activities persisted despite external disruptions, maintaining vibrant artistic and intellectual traditions. Urban centers continued producing sophisticated public art, monuments, and architecture that combined classical and emergent Christian themes.

Preservation and Adaptation of Knowledge

Educational and intellectual institutions remained active, adapting to the changing environment by preserving classical heritage and responding to new social realities. Scholars actively engaged in preserving and interpreting traditional knowledge.

Social and Religious Developments

Administrative Adjustments

Roman provincial administration adjusted significantly to address external threats, enhancing local governance structures and military oversight. This allowed for more effective management of regional challenges and sustained political coherence.

Expansion and Consolidation of Christianity

Christianity continued to expand its influence, with ecclesiastical institutions becoming more deeply integrated into regional social and political frameworks. The period saw increased establishment of churches, monasteries, and Christian communities throughout Eastern Southeast Europe.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

The era from 400 to 411 CE marked a critical phase of intensified migrations, enhanced defensive responses, and sustained cultural and religious developments. These adaptive responses laid crucial foundations for future regional stability and significantly influenced subsequent historical trajectories in Eastern Southeast Europe.

The Sack of Rome and the Fall of an Empire

For fifteen years, an uneasy peace holds between the Visigoths and the Roman Empire, though tensions remain high. Clashes occasionally erupt between Alaric, the ambitious Visigothic leader, and the Germanic generals who wield real power in the Eastern and Western Roman armies.

The fragile balance collapses in 408 CE, when Honorius, the ineffective Western Roman emperor, orders the execution of Stilicho, his most capable general. In the aftermath, the Roman legions massacre the families of 30,000 barbarian soldiers serving in the imperial army, igniting Visigothic fury. This act of betrayal compels Alaric to declare full-scale war against Rome.

The Road to the Sack of Rome

Alaric initially suffers two defeats in Northern Italy, but he remains undeterred. He marches south and besieges Rome, forcing the city’s desperate leaders to negotiate a payoff to lift the siege. However, after being cheated by another faction within the Roman court, Alaric abandons diplomacy and shifts to a decisive military strategy.

Recognizing Rome’s strategic vulnerability, he captures Portus, the city's vital harbor on the Tiber, cutting off its food supply and forcing its gates open. On August 24, 410, Visigothic troops enter Rome through the Salarian Gate, unleashing a devastating three-day sack of the city.

The Shock of Rome’s Fall

Though Rome is no longer the official capital of the Western Roman Empire—the imperial court had relocated to Ravenna for its defensibility—its fall shakes the empire to its core. The city, long considered the eternal heart of Roman civilization, has not been breached by a foreign enemy in nearly 800 years. Its sack marks a symbolic rupture, signaling to contemporaries that the empire is no longer invulnerable.

The impact reverberates across the Mediterranean world. In the Eastern Empire, Saint Jerome laments: "The city that had conquered the world has itself been conquered." Meanwhile, pagans blame Christianity for Rome’s downfall, prompting Augustine of Hippo to pen The City of God, defending the Christian faith against accusations that abandoning the old gods had led to Rome’s ruin.

Though Alaric dies later in 410, his sack of Rome accelerates the decline of the Western Roman Empire, demonstrating that its military and political structures are collapsing under the weight of internal decay and external pressure.

The Middle East: 400–411 CE

Renewed Tensions and Religious Dynamics

The period from 400 to 411 CE sees the fragile stability achieved by the earlier Peace of Acilisene begin to erode, leading to renewed tensions between the Roman (Byzantine) and Sassanid Empires. Although no full-scale war erupts immediately, mutual suspicion and border skirmishes become increasingly frequent, especially along the contested territories of Armenia and Mesopotamia.

Armenia as a Flashpoint

The divided Armenia continues to be a significant point of friction. Roman control in the west remains relatively stable, supported by strong cultural and religious ties to Christianity, which deepen Armenia's alignment with Byzantium. Conversely, Sassanian-controlled eastern Armenia endures intensified Persian cultural and religious influence, emphasizing Zoroastrian orthodoxy and Persian administrative methods. The cultural and religious divergence between these two regions deepens, highlighting Armenia's role as a persistent geopolitical flashpoint.

Christianity's Institutional Growth

Christianity continues its robust institutional development in the Roman territories, shaping regional identities and governance structures. The influence of prominent religious figures, particularly bishops and theologians, expands considerably, consolidating Christian doctrinal authority. Churches and monasteries flourish, becoming not only centers of worship but also vital hubs for education, manuscript preservation, and social services.

Zoroastrian Orthodoxy and Persian Governance

In the Sassanian Empire, the Zoroastrian priesthood's influence grows further under state sponsorship, playing an integral role in governance and social regulation. Religious authorities closely align with the imperial administration to ensure social conformity and stability, reinforcing Persian identity throughout the empire. This period witnesses an increased emphasis on reinforcing traditional Iranian culture and Zoroastrian practices across Persian-held territories.

Economic Continuity and Urban Development

Greater Syria, despite geopolitical uncertainties, maintains considerable economic prosperity under Roman administration. Major cities such as Damascus, Palmyra, and Busra ash Sham continue to thrive, benefiting from established trade routes and robust infrastructure. These cities reinforce their roles as vibrant commercial and cultural centers, fostering continued urban growth and economic stability in the region.

Thus, the era from 400 to 411 CE is characterized by a precarious balance between escalating geopolitical tensions and vigorous religious and economic developments, setting the stage for significant future transformations in the Middle East.

Chinese Buddhist monk and scribe Sehi had taken the name Faxian, "("Splendor of Religious Law").

Stirred by a profound faith to go to India, the "Holy Land" of Buddhism, Faxian has from 399 led pilgrimages through India and Central Asia to gather and copy sacred texts of the various Buddhist schools.

He is most known for his pilgrimage to Lumbini, in Nepal, “the birthplace of Lord Buddha.”

The Gupta empire reaches its political zenith under Chandragupta II, extending far into the Deccan and western India.

A twenty-two-foot- (seven meter-) tall iron pillar represents the remarkable metallurgical advances apparently made under the Gupta dynasty, as the pillar never rusts.

The pillar manufactured by forge welding, is a testament to the high level of skill achieved by ancient Indian iron smiths in the extraction and processing of iron.

The pillar with the statue of Chakra at the top is today at Qutb Minar in Delhi, but its originally location is a place called Vishnupadagiri (meaning “hill with footprint of Lord Vishnu”), identified as modern Udayagiri, situated in the vicinity of Besnagar, Vidisha and Sanchi.

These towns are located about fifty kilometers east of Bhopal, in central India.

There are several aspects to the original site of the pillar at Udayagiri.

Vishnupadagiri is located on the Tropic of Cancer and, therefore, is a center of astronomical studies during the Gupta period.

The Iron Pillar served as a sundial: the early morning shadow of the Iron Pillar falls in the direction of the foot of Anantasayin Vishnu (in one of the panels at Udayagiri) only around the summer solstice (June 21).

The Udayagiri site in general, and the Iron Pillar location in particular, are evidence for the astronomical knowledge that exists in Gupta India.

The pillar bears a Sanskrit inscription in Brahmi script which states that it was erected as a standard in honor of Lord Vishnu.

It also praises the valor and qualities of a king referred to simply as Chandra, who has been identified with the Gupta King Chandragupta II Vikramaditya (375-413).

The Great Invasion of 406 and the Collapse of Roman Defenses

By the early fifth century, the Huns' relentless expansion across Eastern Europe sets off a chain reaction, forcing Germanic and Iranian tribes westward into Roman territory. Among them, the Asdingi and Silingi Vandals, led by King Godigisel, seize the moment as Italy reels from the Visigothic threat, pushing into Roman lands.

Leaving their Upper Danube settlements, they are soon joined by the Alans and some Suebi, forming a vast migratory force. On December 31, 406, this coalition crosses the frozen Rhine at Mainz, launching a massive invasion of Gaul—an event that will permanently alter the fate of the Western Roman Empire.

The Devastation of Gaul and Hispania

The Vandals, Alans, and Suebi, soon followed by Burgundians and bands of Alemanni, sweep across Gaul, overwhelming the federated Franks and Alemanni stationed along the frontiers. The Roman defenses along the Rhine—already strained and undermanned—collapse under the weight of this onslaught.

After devastating northern and central Gaul, the invaders press southward into Hispania, tearing through Roman provinces that have long been integral to the empire’s economic and military stability. The collapse of Roman control in these regions marks a decisive turning point in the decline of the Western Empire.

The Empire’s Mortal Blow

By this time, the empire’s imperial defenses have deteriorated so severely that the Western emperor is forced to abandon Britain, informing its cities that they can no longer rely on Rome for military reinforcements. The Roman army withdraws, leaving the island vulnerable to Saxon, Pictish, and Irish incursions—an event that will eventually lead to the fragmentation of Roman Britain into isolated, competing kingdoms.

For the Western Roman Empire, the Great Invasion of 406 is a mortal wound from which it will never recover. Roman authorities prove incapable of repelling or destroying the invading forces, most of whom will eventually settle in Hispania and North Africa. At the same time, Rome fails to contain the movements of the Franks, Burgundians, and Visigoths in Gaul, further eroding imperial control.

The Role of Internal Disunity

A critical factor in Rome’s inability to resist these invasions is internal fragmentation. In the past, a unified empire, backed by a loyal population willing to make sacrifices, had successfully secured Rome’s borders. However, by the early fifth century, political divisions, power struggles, and economic decay have shattered Rome’s ability to muster the cohesion needed for effective defense.

As the empire weakens from within, its once-powerful legions—stretched thin, riddled with internal conflicts, and increasingly reliant on untrustworthy Germanic federates—prove incapable of withstanding the pressure of continuous invasions. With each successive incursion, the Western Empire’s grasp on its provinces weakens, leading inexorably toward its final dissolution.

Years: 400 - 411

Locations

People

Groups

- Vietnamese people

- Cham people

- Chinese (Han) people

- Lam-Ap, or Lin-yi, (Cham) Kingdom of

- Chinese Empire, Tung (Eastern) Jin Dynasty