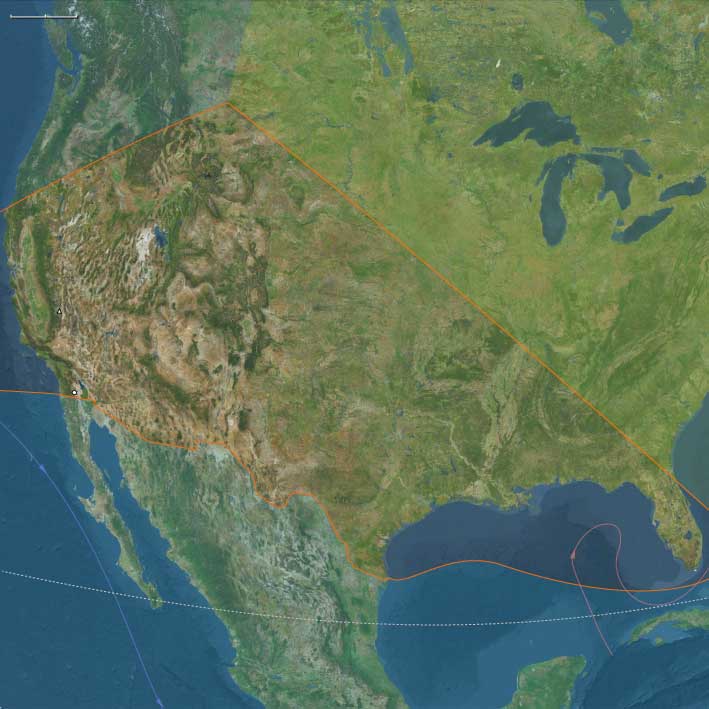

Gulf and Western North America (1552–1563 CE): …

Years: 1552 - 1563

Gulf and Western North America (1552–1563 CE): Indigenous Adaptations and Spanish Consolidation

Spanish Influence and Indigenous Adaptations

Following the initial Spanish explorations, the period 1552 to 1563 witnesses ongoing transformations within indigenous societies in response to sustained European presence. Though direct Spanish colonization remains limited, native peoples continue to adapt to the profound biological and ecological shifts caused by earlier contacts.

Southeastern Societies and Demographic Challenges

In the Southeast, indigenous populations such as the Apalachee, Timucua, Tocobaga, and Calusa experience continued demographic decline due to persistent disease outbreaks introduced by European contact. Societal cohesion weakens as population densities decrease, forcing these tribes to reorganize their traditional lifeways around reduced labor pools and altered environmental conditions.

The Pensacola and the succeeding Leon-Jefferson culture (which directly replaced the Fort Walton culture after 1500), in the Florida panhandle similarly contend with disruptions caused by introduced livestock and diseases. However, these groups persist by modifying their agricultural practices and social structures in response to new ecological realities.

Southwest Cultural Transformations

In the Southwest, indigenous groups such as the Puebloans, Apache, and Navajo peoples gradually integrate limited numbers of horses into their societies through trade and occasional raids on isolated Spanish holdings. While widespread equestrian culture is not yet fully developed, these early acquisitions begin subtly shifting indigenous mobility patterns and interactions.

The disappearance of the Patayan culture by this era highlights broader ecological pressures and transformations occurring across the region. This development underscores how environmental factors compound the stresses brought about by European contact.

Florida’s Indigenous Resilience

In southern and central Florida, complex societies like the Tequesta, Jaega, Ais, and Calusa exhibit considerable resilience despite ongoing challenges from disease and ecological change. These societies, shaped by rich estuarine environments, continue their reliance on marine resources, though their populations are noticeably reduced.

Key Historical Developments

-

Continued demographic decline among southeastern indigenous societies, notably the Apalachee and Timucua.

-

Gradual integration and limited spread of horses among Apache and Navajo peoples.

-

Ecological pressures leading to shifts in indigenous practices, exemplified by the disappearance of the Patayan culture.

-

Persistence and adaptation of Florida’s complex estuarine societies, despite severe demographic losses.

Long-Term Consequences and Historical Significance

This era highlights the resilience and adaptive strategies of indigenous populations facing sustained ecological and demographic pressures following initial European contact. The subtle but increasing incorporation of European-introduced horses by certain groups foreshadows broader cultural transformations yet to come.

Groups

- Chumash people

- Calusa

- Jaega

- Ais people

- Patayan

- Mississippian culture

- Pueblo IV culture

- Tocobaga

- Tohono O'Odham, or Papago (Amerind tribe)

- Apalachee (Amerind tribe)

- Pima people (Amerind tribe)

- Spanish Empire

- Luiseño

- Yokuts

- Mohave people

- Jicarilla Apache

- Mescalero

- Chiricahua

- Acoma Pueblo

- Eight Northern Pueblos (Amerind tribal confederation)

- Apache (Na-Dené tribe)

- Navajo people (Na-Dené tribe)

- Timucua (Amerind tribe)

- Lipan Apache people (Amerind tribe)

- Plains Apache, or Kiowa Apache; also Kiowa-Apache, Naʼisha, Naisha (Amerind tribe)

- Yavapai (Amerind tribe)

- Western Apache

- Spanish Florida