Gold is discovered in South Island’s Otago …

Years: 1861 - 1861

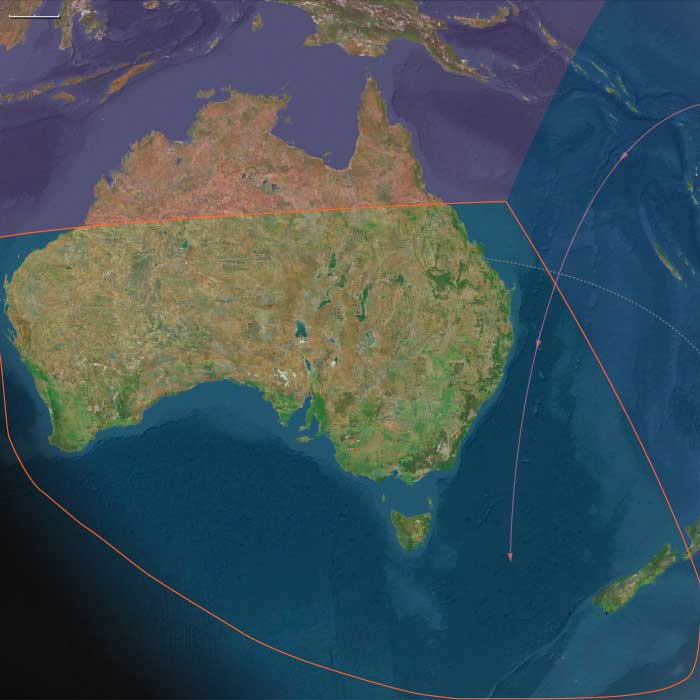

Gold is discovered in South Island’s Otago region in 1861, drawing thousands of gold seekers from Australia and North America.

Locations

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 14901 total

Australia, its population having swollen threefold in a decade to nearly twelve hundred thousand, has exported more than twenty-four million dollars worth of gold by 1861.

The goldfields begin to decline about this time.

In 1858 the Imperial Russian Navy had leased a strip of Nagasaki Bay coastline across the village of Inasa as a winter anchorage for the Chinese Flotilla's emerging Pacific Fleet (all domestic anchorages froze up in winter).

Flotilla commander Admiral Ivan Likhachev realized the dangers of basing the fleet in a foreign port, and settled on establishing a permanent base in Tsushima Island in the Korea Strait.

He is aware that the British had attempted to set their flag there in 1859 and had conducted hydrographic surveys around the island in 1855.

In 1860 he had requested a go-ahead from the government in Saint Petersburg; the cautious foreign minister, Alexander Gorchakov, had ruled out any incursions against British interests, while General Admiral Konstantin Nikolayevich suggested making a private deal with the head of Tsushima-Fuchū Domain, as long as it did not disturb "the West".

In case of failure the Russian authorities will deny all knowledge of the expedition.

Britain and France, which have wrested major concessions for themselves from the Chinese in the First and Second Opium Wars after 1860, and being more willing to deal with the weak Qing administration than contend with the uncertainties of a Taiping regime, finally decide it is in their own best interest to come to the aid of the Manchus.

Further difficulties in China follow in the wake of the Second Opium War.

An illegal opium trade carried on by smugglers in south China encourages gangsterism and piracy, and the activity will eventually become linked with powerful secret societies in the south of China.

With the end of the Second Opium War in 1858, the legalization of opium in China had quickly transformed the country into the world's leading producer.

Chinese officials encourage local production, and poppy cultivation spreads beyond the southwest to nearly every province.

Alexander II’s Act of Emancipation frees Russia's serfs in March 1861, amounting to the liquidation of serf dependence previously suffered by Russian peasants, ushering in an era of reform, and causing the influx of large numbers of poor into the capital.

Tenements are erected on the outskirts, and nascent industry springs up, surpassing Moscow in population and industrial growth.

The publication of Zhitie (Life) in 1860, the autobiography of martyred Old Believer archpriest Avvakum, a Russian protopope of Kazan Cathedral on Red Square who led the opposition to Patriarch Nikon's reforms of the Russian Orthodox Church, will influence such later Russian novelists as Fyodor Dostoevsky, Ivan Turgenev and Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

A Hungarian Diet convoked in 1861 is dissolved after a few weeks, because the gap between the Hungarians' views and those of Franz Joseph and his centralist ministry in Vienna are still too wide to be bridged.

Absolutism is reimposed, but the pressure of international and internal economic difficulties gradually drives Francis Joseph to further concessions.

The European powers and the Ottoman Empire ratify Cuza's election after discussions in Paris, and the United Principalities officially become Romania in 1861.

Cuza initiates a reform program almost immediately.

Encountering resistance from oligarchic boyars, the prince appeals to the masses and holds a referendum that approve constitutional provisions giving him broad powers to implement his program.

The government improves roads, founds the universities of Bucharest and Iasi, bans the use of Greek in churches and monasteries, and secularizes monastic property.

Cuza also signs an agrarian law that eliminates serfdom, tithes, and forced labor and allows peasants to acquire land.

Unfortunately, the new holdings are often too expensive for the peasants and too small to provide self-sufficiency; consequently, the peasantry's lot deteriorates.

Bahrain, a small island group in the Persian Gulf controlled for centuries by the Khalifa family, becomes a British protectorate in 1861.

The binding treaty of protection, known as the Perpetual Truce of Peace and Friendship, ushers in the period of colonialism in Bahrain.

The treaty, similar to those entered into by the British Government with the other Persian Gulf principalities, specifies that the ruler cannot dispose of any of his territory except to the United Kingdom and cannot enter into relationships with any foreign government without British consent.

In return the British promise to protect Bahrain from all aggression by sea and to lend support in case of land attack.

More important, the British promise to support the rule of the Al Khalifa in Bahrain, securing its unstable position as rulers of the country.

The beginning of the British policy of consultation with Indians is another significant result of the mutiny.

The Legislative Council of 1853 had contained only Europeans and had behaved arrogantly as if it had been a full-fledged parliament.

It is widely felt that lack of communication with Indian opinion had helped to precipitate the crisis.

Accordingly, the new council of 1861 is given an Indian-nominated element.

The educational and public works programs, roads, railways, telegraphs, and irrigation continue with little interruption; in fact, some are stimulated by the thought of their value for the transport of troops in a crisis, but the insensitive, British-imposed social measures that have affected Hindu society have come to an abrupt end.