Northern West Indies (1540–1683 CE): Colonization, Contest, …

Years: 1540 - 1683

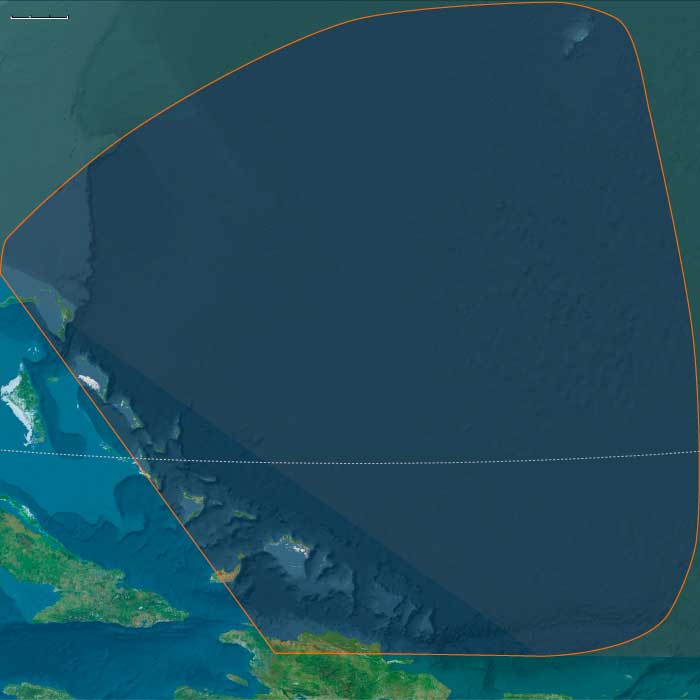

Northern West Indies (1540–1683 CE): Colonization, Contest, and Survival

Geographic & Environmental Context

The subregion of Northern West Indies includes Bermuda, the Turks and Caicos, northern Hispaniola, and the Outer Bahamas (Grand Bahama, Abaco, Eleuthera, Cat Island, San Salvador, Long Island, Crooked Island, Mayaguana, Little Inagua, and eastern Great Inagua). The Inner Bahamas belong to the Western West Indies. Anchors included the Bahama Banks, the Caicos archipelago, Bermuda’s cedar-clad heights, and the Cibao Valley of northern Hispaniola. These islands combined shallow reefs and sandy cays with fertile valleys and rugged highlands. The Gulf Stream swept nearby, shaping both ecology and navigation.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age persisted with cooler conditions and more frequent hurricanes. Bermuda endured severe storms but remained fertile with cedar forests. The Bahamas and Caicos saw erosion and overwash on low-lying cays, while Hispaniola’s northern valleys sustained farming despite drought cycles.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Spanish Hispaniola: The north coast became a hinterland to Santo Domingo, dotted with cattle ranches (hatos), small farms, and depopulated Taíno villages. Enslaved Africans provided labor for ranching, mining, and coastal outposts.

-

Bahamas and Caicos: Spaniards forcibly removed most Indigenous Lucayans by the mid-16th century; the islands were sparsely populated until English settlements later.

-

Bermuda: Settled by the English after the wreck of the Sea Venture (1609). Colonists developed tobacco fields, small farms, and shipbuilding industries, relying heavily on enslaved Africans and indentured servants.

Technology & Material Culture

Spanish colonists used iron tools, firearms, livestock, and European crops. Ranching technologies dominated Hispaniola’s north coast. English Bermuda developed fortifications, cedar shipyards, and distinctive vernacular houses with rain-catching roofs. Enslaved Africans preserved elements of material culture in tools, cooking, and ritual objects.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Spanish fleets linked Hispaniola with Havana, Veracruz, and Seville.

-

English Bermuda became a provisioning and shipbuilding hub for Atlantic ventures.

-

The Bahamas and Caicos, sparsely inhabited, served as navigation markers, pirate refuges, and later English staging grounds.

-

African slave routes tied all islands into the transatlantic trade.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Spanish Catholic rituals and festivals dominated Hispaniola, though African and Taíno traditions survived in syncretic forms.

-

Bermuda’s English colonists imposed Anglican worship while enslaved Africans blended Christianity with African cosmologies.

-

Place names, churches, and forts symbolized imperial claims.

-

Pirate legends and mariner folklore began attaching symbolic meaning to the Bahamas’ reefs and cays.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Depopulation of the Bahamas allowed ecosystems to recover, though invasive species (pigs, goats) altered islands. On Hispaniola, cattle ranching adapted to drier conditions. Bermuda colonists coped with hurricanes by fortifying homes and adapting agriculture to thin soils. African and Indigenous resilience persisted in foodways (cassava, okra, plantains) and rituals of survival.

Transition

By 1683 CE, the Northern West Indies was divided between Spanish Hispaniola and English Bermuda, while the Bahamas and Caicos hovered as contested spaces, frequented by privateers. Indigenous populations had largely vanished, but African and European communities reshaped the region into a maritime frontier of empire, slavery, and resistance.

People

Groups

- Arawak peoples (Amerind tribe)

- Taíno

- Lucayans

- French people (Latins)

- English people

- Spain, Habsburg Kingdom of

- Spaniards (Latins)

- Eleutheran Adventurers