The West Indies (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): …

Years: 6093BCE - 4366BCE

The West Indies (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Archaic Islands and the First Canoe Networks

Geographic & Environmental Context

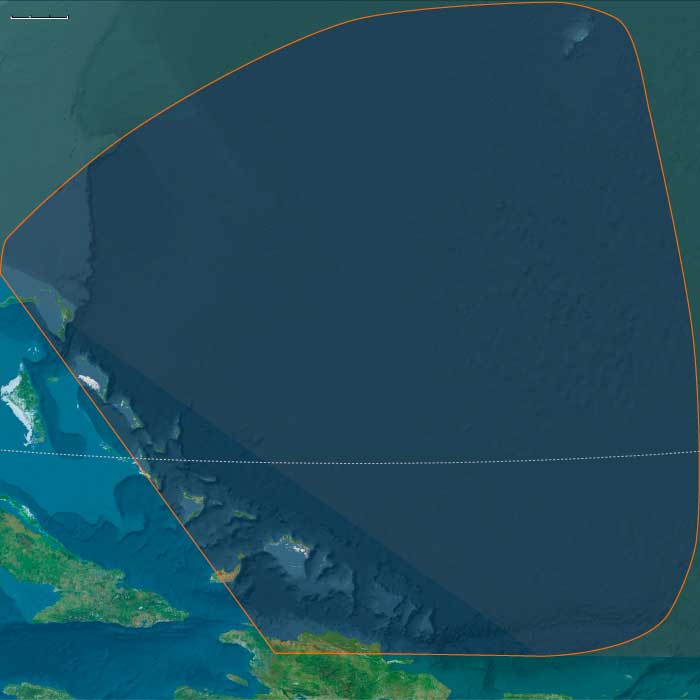

During the Middle Holocene, The West Indies—stretching from Cuba and Jamaica through Hispaniola and Puerto Rico to the Leeward and Windward chains and Trinidad & Tobago—was a world in the making: an archipelago of rising reefs, deepening channels, and newly stabilized shorelines.

Sea levels approached modern positions by 6000 BCE, flooding former coastal plains and isolating the great islands. The result was a chain of biogeographic bridges and barriers, each sustaining unique combinations of flora, fauna, and marine resources.

Three interconnected island groups defined this early world:

-

The Western West Indies—Cuba, Jamaica, the Caymans, and western Hispaniola—where broad shelves, mangrove lagoons, and turtle-rich cays invited repeated human visitation.

-

The Eastern West Indies—Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Lesser Antilles, and Trinidad & Tobago—where small fertile valleys and volcanic arcs created microecologies for horticulture and reef harvesting.

-

The Northern arc (Bahamas, Turks & Caicos, northern Hispaniola)—not yet settled but already part of the region’s ecological sphere.

Across these scattered lands, the Middle Holocene marked the first sustained human presence: mobile foragers and fishers adapting to island diversity and testing the limits of ocean voyaging.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm optimum stabilized weather patterns and brought mild, humid conditions to the Caribbean basin.

-

Sea level rise slowed, producing permanent coastlines, wide coral reefs, and mangrove forests.

-

Periodic hurricanes and tropical storms sculpted barrier spits and inland lagoons, enriching estuarine productivity.

-

Seasonal rainfall and freshwater springs on volcanic islands supported both terrestrial and coastal food webs.

This climatic harmony fostered the expansion of inter-island ecosystems—reef, lagoon, forest, and river—each supporting specialized human economies.

Subsistence & Settlement

Throughout the archipelago, Archaic foragers developed flexible coastal–inland rounds:

-

On the larger western islands (Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica), semi-permanent bayside hamlets appeared, where communities harvested shellfish, turtles, and manatees while collecting fruits, palms, and root crops from nearby forests.

-

In the eastern and southern chains (Puerto Rico to Trinidad), coastal gardens and tended groves hinted at proto-arboriculture—the deliberate maintenance of edible trees near camp sites.

-

Trinidad & Tobago, at the mouth of the Orinoco, served as the continental gateway, linking island foragers to South American riverine networks and tropical forest goods.

-

Fishing technologies—nets, weirs, and fish traps—grew in sophistication, while dugout canoes allowed regular travel among near islands and barrier cays.

These were maritime foragers rather than agricultural colonists: communities that lived by season, tide, and current.

Technology & Material Culture

Material culture across the West Indies reflected continuity and innovation:

-

Bone fishhooks, shell adzes, and net weights were common, often finely worked for durability.

-

Stone and coral tools served for woodcarving, basketry, and canoe construction.

-

Dugout canoes carved from hardwoods provided reliable transport between islands, inaugurating the first inter-island navigation circuits.

-

In the eastern arc, toolkits diversified to include ornaments, shell beads, and small polished stones, indicating both craft specialization and social signaling.

Though ceramics had yet to appear, these technologies reveal an emerging maritime toolkit that would support later horticultural societies.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

By the mid-Holocene, the Caribbean had become a connected sea:

-

Canoe corridors traced predictable wind and current patterns through the Windward Passage, the Anegada Channel, and the Grenada–Trinidad–Orinoco chain.

-

Trinidad & Tobago acted as a continental hinge, mediating goods and knowledge from the South American coast—nuts, fibers, resins—into the island world.

-

Along the western islands, exploratory runs reached the Caymans and outer banks for turtle and salt gathering, establishing the first trans-archipelago foraging networks.

These routes foreshadowed the later ceramic-age migrations, but already they sustained regular contact and ecological knowledge exchange among island communities.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Early West Indian societies embedded their worldviews in both material and ritual practice:

-

Ancestor stones and shell middens served as focal points for communal feasting and remembrance.

-

Repeated use of reef-head shelters and beach ridges for seasonal gatherings transformed natural features into sacred sites.

-

**Marine animals—manatees, sharks, and turtles—**featured prominently in ritual life, symbolizing fertility and renewal.

-

Social memory was carried through song and route, as canoe voyages linked distant coasts into a shared maritime consciousness.

These were cultures of continuity, where the rhythm of tide and season structured both livelihood and belief.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Adaptation depended on mobility, redundancy, and ecological diversification:

-

Reef–grove pairing—the combined exploitation of coral flats and forest resources—provided food security through storms and dry spells.

-

Canoe mobility enabled rapid relocation when hurricanes or resource depletion struck.

-

Multi-island kin networks ensured social and material support, distributing risk across the archipelago.

-

Shell middens and managed groves acted as long-term stores of nutrients and food sources, evidence of environmental engineering on an island scale.

This system produced resilient coastal societies, sustained not by domestication but by precise ecological management.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, the West Indies had entered a phase of established maritime foraging and inter-island exchange.

Communities across Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and the Lesser Antilles shared a common technological and ecological foundation—canoes, nets, shell tools, and coastal gardens—that would, centuries later, enable the Saladoid and Arawakan expansions from the South American mainland.

The Middle Holocene Caribbean thus stands as the protohistory of navigation and adaptation in the Americas: a world where people learned to live with the sea, mapping its winds, reefs, and stars long before the first ceramics or crops arrived.

The archipelago was not yet agricultural—but it was already civilizational in scale, a maritime network of memory and motion stretching from the Orinoco to the Windward Passage.