Antarctica (2637 – 910 BCE): The Ice …

Years: 2637BCE - 910BCE

Antarctica (2637 – 910 BCE): The Ice Plateau and the Living Margins

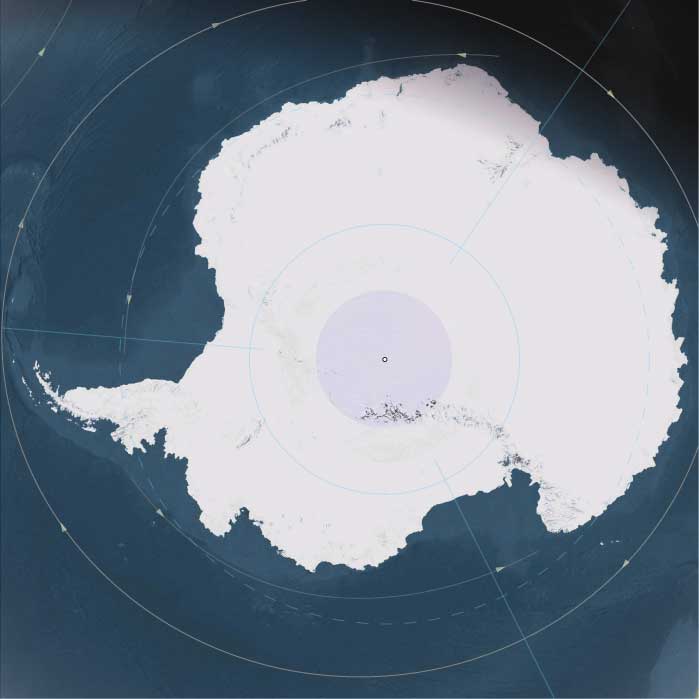

Regional Overview

In Early Antiquity, the Antarctic realm was a planet unto itself — a continent of glacial silence, rimmed by life-rich seas and subantarctic refuges.

Across the age of bronze and early iron elsewhere, Antarctica remained unpeopled, unseen, and unimagined.

Yet its climate rhythms, ocean currents, and seasonal productivity already shaped the biospheric balance of the southern hemisphere.

From the frozen plateaus of East Antarctica to the storm-wracked islands of the Scotia Arc and subantarctic belts, the region functioned as Earth’s ultimate frontier of wind, ice, and oceanic life.

Geography & Climate

Antarctica’s physical duality was already pronounced:

-

East Antarctica — a massive, stable shield buried beneath more than three kilometers of ice, crowned by domes exceeding 3,000 m in elevation.

-

West Antarctica — a chain of lower marine basins, ice domes, and the long finger of the Antarctic Peninsula projecting toward South America.

Across both, climate was hyper-polar:

-

Interior temperatures fell below –60 °C in winter; katabatic winds scoured snow from the slopes.

-

Summer brought continuous daylight along coasts, minor melting at exposed oases, and marine polynyas that pulsed with plankton blooms.

-

Annual precipitation was minimal — millimeters of water equivalent over the plateau — but coastal snow accumulation fed glaciers that surged toward the sea.

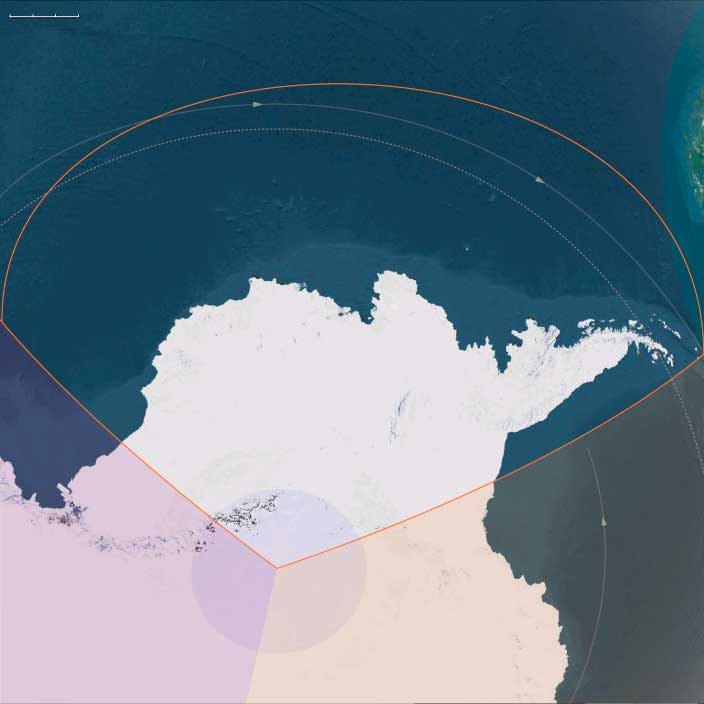

Eastern East Antarctica: The Polar Plateau’s Eastern Expanse

From the Ross Sea to the Amery Ice Shelf, the vast plateau remained a world of frozen calm.

Its katabatic winds carved snow dunes and shaped the desert of ice; its glaciers fed the largest ice shelves on Earth.

Life existed only at the margins — microbial mats in coastal oases, Adélie and early Emperor penguins nesting on summer ice, and seals resting along stable leads.

For humans, it was beyond imagination: a realm unseen, unreachable, and unknown.

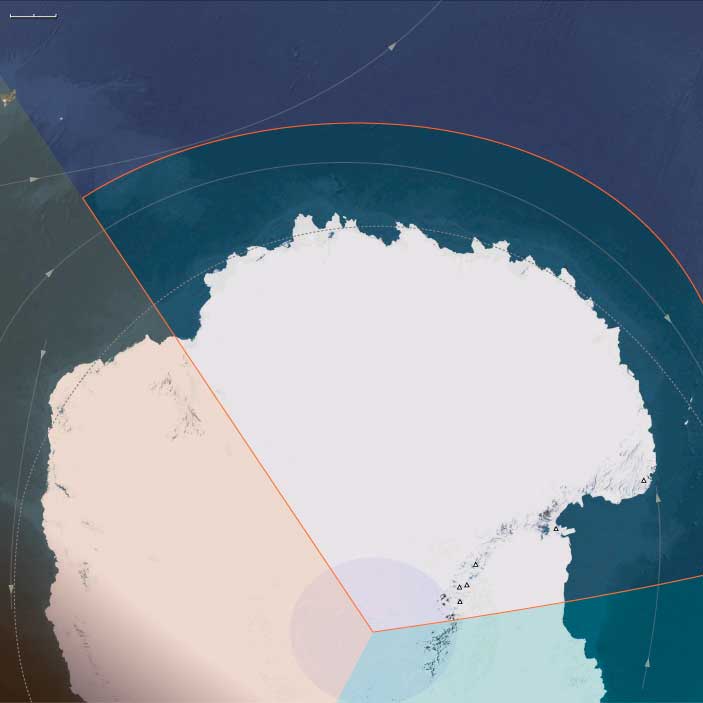

Western East Antarctica: Icebound Shores and Subantarctic Refuges

East Antarctica’s outer arc merged seaward into a chain of subantarctic islands — South Georgia, the South Sandwiches, Bouvet, the South Orkneys, and the Prince Edward–Marion and western Kerguelen groups.

Here, in the westerly wind belt, marine life flourished under constant gales:

-

Penguin and albatross colonies blanketed every ice-free slope.

-

Seals and whales followed dense krill fields around volcanic and glaciated coasts.

These islands were far milder than the continental interior, sustaining tussock grasslands, mosses, and lichensnourished by guano and rainfall.

They were the only true oases of warmth and biological abundance within the Antarctic system.

West Antarctica: Fragmented Ice Lands and Coastal Wildlife Havens

Across the Antarctic Peninsula and the Amundsen–Bellingshausen Seas, the continent fractured into smaller ice domes and marine basins.

Here, seasonal melting created ice-free headlands that hosted dense Adélie and gentoo penguin rookeries, petrel colonies, and seal haul-outs.

Peter I Island, a volcanic outlier adrift in the Bellingshausen Sea, mirrored this pattern on a miniature scale — an isolated rock fortress used seasonally by seabirds and seals.

These shores marked the northernmost limit of the polar continent, where sunlight and upwelling met to generate the most productive waters of the Southern Ocean.

Ecological Systems & Biological Productivity

The Antarctic ecosystem revolved around a single seasonal pulse:

-

Spring–Summer: Melting sea ice released nutrients, triggering phytoplankton blooms that fueled krill swarms, seabirds, seals, and whales.

-

Autumn–Winter: Sea ice re-formed; most species migrated northward or entered dormancy.

From microbial mats in the Vestfold Hills to krill shoals spanning hundreds of kilometers, life followed a rhythm synchronized with light and ice — an enduring cycle of abundance and dormancy that predated human awareness by millennia.

Human Absence & Conceptual Geography

Antarctica lay completely outside the cognitive map of the Bronze and Iron Age world.

Even the most adventurous maritime cultures of the Indian and Pacific Oceans — Austronesians, Phoenicians, Egyptians, or South Americans — never neared these latitudes.

To ancient cosmologies, the far south was an unimaginable void, a theoretical counterbalance to known lands rather than a physical place.

Antarctica’s only history in this epoch was ecological, not human.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

The resilience of this polar system rested on feedbacks unique to ice-covered worlds:

-

Glacial advance and retreat periodically reconfigured coasts, creating new nesting terraces.

-

Ashfall from Antarctic and subantarctic volcanoes refreshed soils with minerals.

-

Peat and moss beds stabilized microclimates in rare oases.

-

Marine upwelling and krill flexibility ensured food web continuity through climatic oscillations.

Every storm, eruption, and freeze–thaw cycle renewed rather than destroyed the ecological fabric.

Transition

By 910 BCE, the Antarctic realm stood in late-Holocene equilibrium:

-

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet dominated the continent;

-

Subantarctic islands thrived with bird and seal colonies;

-

West Antarctic shelves hosted rich summer ecosystems;

-

And humanity remained utterly absent.

Antarctica entered the first millennium BCE as a closed world of ice and life, sustaining the planet’s southern oceanic engine — a realm of perpetual cold, unmarked by any human hand, yet central to Earth’s climate and biological stability.