Polynesia (676–819 CE): Chiefly Horizons, Sacred Genealogies, …

Years: 676 - 819

Polynesia (676–819 CE): Chiefly Horizons, Sacred Genealogies, and the Oceanic Web

Geographic & Environmental Context

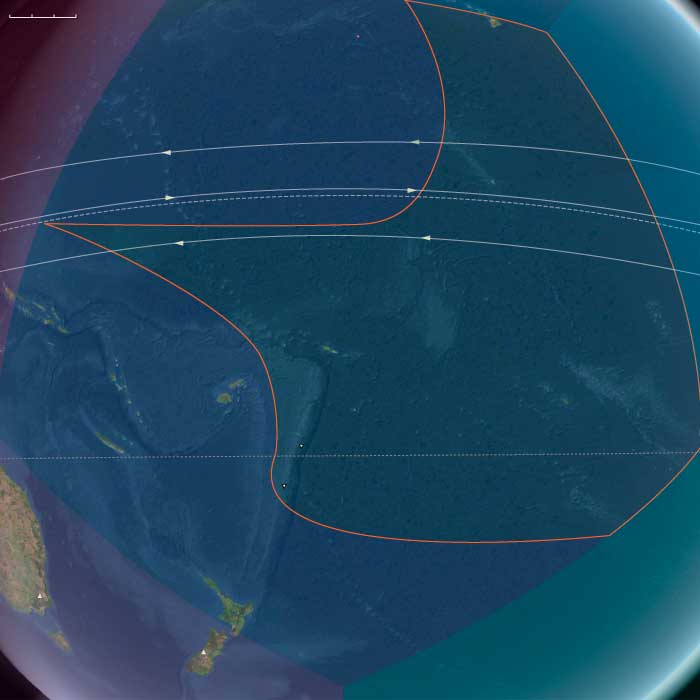

By the late 7th and early 9th centuries CE, Polynesia had fully matured as a cultural world—its islands scattered across a vast triangle stretching from Hawai‘i (North Polynesia) to Tonga and Samoa (West Polynesia) and to the far-flung eastern arc of Mangareva, Pitcairn, and Rapa Nui (East Polynesia).

The region comprised a spectrum of environments: high volcanic islands such as Tongatapu, Upolu, Tahiti, and Hawai‘i with fertile soils and perennial streams; mid-ocean atolls such as Tokelau, Tuvalu, and the Cooks dependent on rainwater and lagoon productivity; and the dry, isolated islands of the far southeast where ingenious field systems emerged. Despite their remoteness, these island worlds were joined by voyaging canoes, kinship alliances, and ritual exchanges that carried ideas, crops, and people across thousands of kilometers.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The late Holocene climatic stability persisted across the Pacific. Trade winds blew reliably, seas were calm enough for open-ocean voyages, and ENSO variability remained modest. High islands enjoyed dependable rainfall that sustained breadfruit, banana, and taro agriculture, while atolls relied on coconuts, fish, and preserved breadfruit. Only in the eastern outliers did dryness and wind pose serious challenges—factors that spurred early Polynesian innovation in rock-mulch gardening and rain-fed irrigation.

Societies & Political Developments

West Polynesia: Hierarchies and Monumental Foundations

In Tonga, Samoa, and the Cook and Society Islands, population growth and inter-island competition gave rise to stratified chiefdoms. The Tu‘i Tonga dynasty began to consolidate authority, erecting massive earthen and stone mounds (langi) that anchored sacred kingship. Samoa maintained a federated chiefly system—matai councils of lineage heads balancing consensus and prestige. Across the region, authority blended divine ancestry with pragmatic leadership, expressed in ceremonies of kava drinking, tattooing, and oratory. Monumental platforms and marae sanctuaries symbolized unity between ancestors, land, and sea.

North Polynesia: Consolidation and Cultural Refinement

In Hawai‘i and the northern chain, societies became more territorial and structured, their valleys divided among chiefly lines (ali‘i). Irrigated taro terraces expanded in O‘ahu and Maui’s windward valleys; fishponds (loko i‘a) were engineered to capture tides and breed mullet. Ritualized chiefly exchanges—feasting, dancing, and tribute distribution—strengthened social cohesion. While navigation routes between Hawai‘i and the central Pacific likely thinned, local voyaging remained vigorous among the northern islands.

East Polynesia: Frontier Communities and Ancestral Memory

Far to the southeast, settlers in Mangareva, Pitcairn, and Rapa Nui lived in isolation, maintaining small but resilient societies. Chiefs presided over kin-based villages cultivating taro, yam, and sweet potato in terraces and rock gardens. Ahu shrines and standing stones emerged as ancestral foci—the embryonic stage of the moai tradition that would later define Rapa Nui. Canoes connected these islands intermittently, sustaining exchange in stone tools, shell ornaments, and genealogical lore. Here, voyaging became both a practical necessity and a sacred remembrance.

Economy & Exchange Networks

Across Polynesia, horticulture and arboriculture formed the economic base—taro, yam, breadfruit, banana, and coconut supplemented by pigs, chickens, and dogs introduced generations earlier.

-

West Polynesia exported shell valuables and basalt adzes through Tonga–Samoa–Fiji circuits.

-

North Polynesia relied on local specialization: irrigated taro inland, salt and fish from coasts.

-

East Polynesia used inter-island reciprocity to mitigate ecological limits.

Voyaging remained integral: double-hulled canoes carried goods, spouses, and genealogies; their movement stitched the region into a maritime commonwealth of mutual awareness, even as local identities deepened.

Technology & Material Culture

The lashed-lug canoe with mat sails epitomized Polynesian mastery of wood, fiber, and hydrodynamics. Stone adzes, coral files, and shell scrapers refined woodworking and house construction. Fine tapa cloth, dyed red, black, or yellow, became a medium of tribute and ceremony. Ornaments in whale ivory, shell, and bone displayed chiefly status. In the east, basalt and coral tools from Mangareva and Pitcairn circulated in small but steady exchange spheres.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Polynesian cosmology centered on genealogy (whakapapa, gafa)—the sacred chain linking gods, chiefs, and commoners. Myths of Tangaloa, Tane, and Pele described creation through navigation and transformation.

Ritual life unfolded in marae and heiau—open-air temples marked by coral or basalt pavements where offerings and kava libations honored gods and ancestors. Song, dance, and tattooing codified memory, rank, and identity. Across the ocean, shared motifs—spiral designs, triangular tattoos, red sacred coloration—testify to a living network of cultural dialogue.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Tonga and Samoa: irrigated taro and arboriculture balanced protein from lagoons.

-

Hawai‘i: fishpond systems, diversified valley agriculture, and ritual resource management sustained dense populations.

-

Rapa Nui: stone-mulch gardens and windbreaks stabilized soils.

-

Atolls: preserved breadfruit paste, coconut water, and dried fish underpinned food security.

Polynesians treated ecology as a sacred partnership—land (fenua, ʻāina) and sea (moana) were both kin and deity.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

West Polynesia remained the political and ritual center, radiating influence outward through marriage alliances, kava rites, and trade. Central Polynesian canoes ventured along the Tonga–Samoa–Cook–Tahiti axis, while smaller craft maintained contact across the Tuvalu–Tokelau–Pukapuka chain. The far east and north were increasingly autonomous, but oral traditions preserved the idea of a connected “sea of islands,” navigable through shared stars and genealogies.

Transition (After 819 CE)

By the early 9th century, Polynesia had reached a cultural equilibrium:

-

West Polynesia anchored a network of monumental chiefdoms under the rising Tu‘i Tonga.

-

North Polynesia fostered intricate irrigation, aquaculture, and lineage-based leadership.

-

East Polynesia, though remote, developed distinct ancestral monuments that anticipated later innovation.

This was an age of stability and synthesis—when Polynesian societies balanced expansion and rootedness, hierarchy and reciprocity, and the sacred ocean continued to bind their far-flung worlds into one cultural continuum.