Micronesia (964 – 1107 CE): Navigators, Chiefdoms, …

Years: 964 - 1107

Micronesia (964 – 1107 CE): Navigators, Chiefdoms, and the Architecture of the Sea

Geographic and Environmental Context

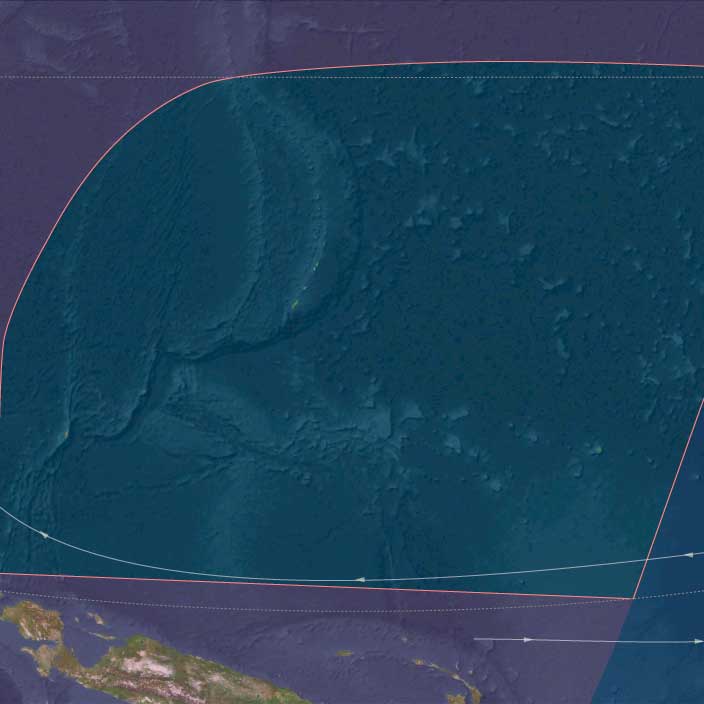

Micronesia in the Lower High Medieval Age stretched across the western and central Pacific — from the Mariana Islands and Yap–Chuuk–Palau complex in the west to the Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Kosrae, and Nauru in the east.

This immense maritime realm spanned more than 7 million km² of ocean, linking high volcanic islands, limestone plateaus, and coral atolls into one of the world’s most intricately networked seascapes.

High islands such as Kosrae, Yap, Palau, and Chuuk offered freshwater, fertile valleys, and taro swamps, while the low atolls of the Marshalls and Kiribati relied on arboriculture, preserved breadfruit, and lagoon fishing.

Canoe routes — the region’s highways — carried tribute, marriage partners, and ritual obligations across hundreds of miles of open sea.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950 – 1250 CE) brought relative climatic stability across Micronesia.

Steady trade winds and reliable rainfall favored arboriculture on high islands, while atolls remained exposed to the cycles of El Niño drought and La Niña storm.

Typhoons periodically stripped atoll groves, yet flexible voyaging networks and food-preservation technologies ensured regional resilience.

Kosrae’s fertile highlands and Yap’s well-watered valleys acted as ecological anchors, supplying atoll populations during shortages.

Societies and Political Developments

Across Micronesia, new forms of chiefly hierarchy, monumental architecture, and ritualized navigation emerged.

-

West Micronesia saw the rise of prestige-based systems that knit scattered islands into spheres of obligation and alliance.

-

On Yap, powerful chiefs coordinated the early sawei network — a system of reciprocal tribute linking outer atolls (Ulithi, Woleai, Lamotrek, Satawal) to the central island.

-

In the Marianas, the first latte-stone foundations appeared in the south, marking the houses of emerging chiefly lineages (maga’låhi).

-

Chuuk developed lagoon-centered chiefdoms, with fortified hill refuges and clan-based authority.

-

Palau formed councils of chiefs that regulated warfare and fertility rituals through monumental meeting houses (bai).

-

-

East Micronesia produced a parallel flowering of centralized leadership.

-

On Kosrae, the rise of a sacred kingship (tokosra) laid the foundations for the later monumental city of Lelu, symbolizing divine rule and architectural ambition.

-

In the Marshall Islands and Kiribati, atoll chiefdoms expanded, controlling land, lagoon tenure, and fishing rights through hereditary chieftainship.

-

Nauru sustained smaller clan federations that prized self-sufficiency while maintaining ritual and trade ties.

-

Together, these systems articulated a continuum from loosely federated atolls to nascent maritime kingdoms.

Economy and Trade

Micronesian economies balanced horticulture, arboriculture, and fishing within extensive exchange networks.

-

Staples: breadfruit, coconut, taro, yam, and pandanus supported both subsistence and ceremonial feasting.

-

Animal resources: reef fish, deep-sea tuna, turtles, and seabirds supplemented diets; pigs and chickens were scarce but symbolically significant.

-

Exchange circuits:

-

Yap ⇄ Outer Islands: preserved breadfruit paste, fiber mats, and shells moved inward; Yap exported canoe timber, turmeric, and prestige stones — the embryonic form of its later rai stone economy.

-

Kosrae ⇄ Marshalls/Kiribati: tribute and trade goods — canoes, mats, and shell ornaments — circulated along sea lanes radiating from Kosrae’s high island hub.

-

Palau ⇄ Yap ⇄ Philippines: regional contact zones carried ironwood, taro, and ceremonial items.

-

Marianas: pottery, fishhooks, and ornaments moved among northern and southern islands, strengthening kinship and ritual ties.

-

These exchanges bound together hundreds of communities into a resilient, inter-dependent maritime economy.

Subsistence and Technology

Micronesian subsistence rested on precise ecological management and technological ingenuity:

-

Agriculture and arboriculture: irrigated taro swamps in Palau and Yap; coconut and breadfruit groves on atolls; pandanus fiber for mats and sails.

-

Food preservation: fermented breadfruit pits (bwiro, ma) ensured multi-year reserves; smoked fish and dried pandanus paste sustained long voyages.

-

Canoe technology: double-hulled and outrigger craft with crab-claw sails allowed voyages of 500 km or more.

-

Navigation: wayfinders memorized star paths, currents, swells, and bird flights; in the Marshalls, stick chartsencoded oceanography as a tangible map of motion.

-

Architecture: early stone construction began at Kosrae, foreshadowing monumental urbanism; latte stones in the Marianas rose as durable symbols of lineage permanence.

Together these technologies represented a unique synthesis of practical engineering and cosmological expression.

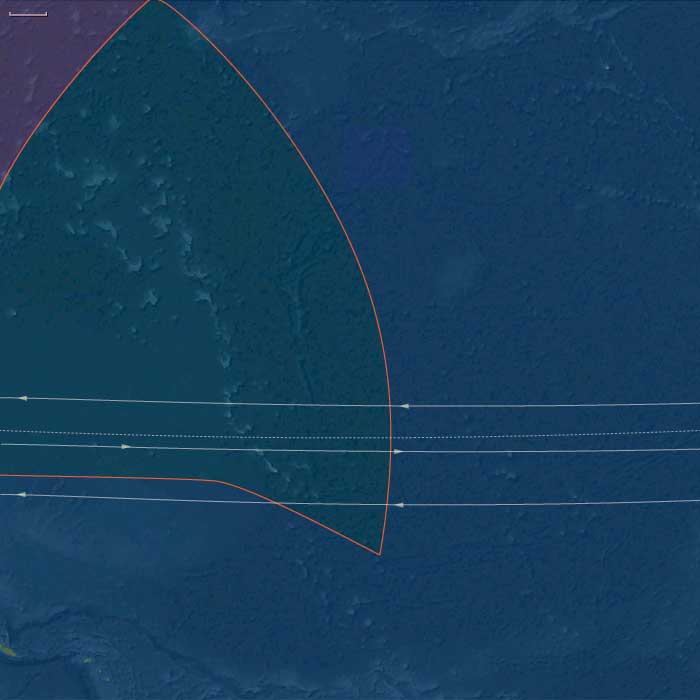

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Micronesian navigation transformed the ocean into a lived landscape.

-

The sawei network radiated from Yap, binding the Caroline atolls through tribute and protection.

-

Chuuk Lagoon linked dozens of islets by daily canoe traffic, maintaining internal unity.

-

Palau extended voyaging toward Yap and western archipelagos.

-

In the east, Kosrae acted as a hub connecting the Carolines to the Marshalls and Kiribati.

-

The Marianas maintained north–south cohesion through regular voyages along their island chain.

Every voyage was simultaneously economic, political, and sacred — reaffirming kinship, redistributing wealth, and renewing cosmological order.

Belief and Symbolism

Micronesian spirituality bound ocean, ancestry, and navigation into a single sacred system.

-

On Kosrae, divine kingship fused governance with cosmic authority; shrines and tombs sanctified the ruler’s lineage.

-

On Yap, chiefs embodied mana, and stone shrines anchored prestige rituals.

-

Palauan fertility cults linked women’s authority to taro and lagoon abundance; bai meeting houses were carved with mythic histories.

-

Marianas’ latte stones symbolized ancestral endurance and legitimacy.

-

Throughout the region, canoes were consecrated as sacred beings — their keels blessed before launch, their voyages accompanied by chant and offering.

The sea itself was understood as a spiritual domain populated by ancestors and deities who guided wayfinders through dreams and omens.

Adaptation and Resilience

Micronesian societies perfected strategies for survival in fragile island ecologies:

-

Multi-island networks distributed risk across space — if one atoll suffered drought, others supplied aid.

-

Food preservation and arboricultural diversity guaranteed continuity through climatic swings.

-

Chiefly redistribution transformed political authority into ecological stewardship, ensuring equitable sharing of scarce resources.

-

Navigation schools safeguarded knowledge transmission, maintaining cultural and environmental literacy across generations.

These adaptive systems turned geographic isolation into a source of strength.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, Micronesia had matured into a maritime commonwealth of atoll chiefdoms and high-island centersbound by navigation, exchange, and ritual.

-

Yap presided over the western tribute network that foreshadowed the full sawei system.

-

Kosrae emerged as the eastern keystone of political and architectural innovation, anticipating the monumental complex of Lelu.

-

Palau, Chuuk, and the Marianas consolidated hierarchical chiefdoms defined by ritual architecture and clan councils.

-

Across the entire region, mastery of wayfinding and resource management created one of the most sophisticated non-literate navigational civilizations in world history.

Micronesia thus entered the twelfth century as a sea of connected sovereignties — its people unified not by land, but by the ocean paths that carried memory, exchange, and sacred order from horizon to horizon.