Micronesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): Atoll …

Years: 909BCE - 819

Micronesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): Atoll Worlds, High-Island Hubs, and the Geometry of the Ocean

Regional Overview

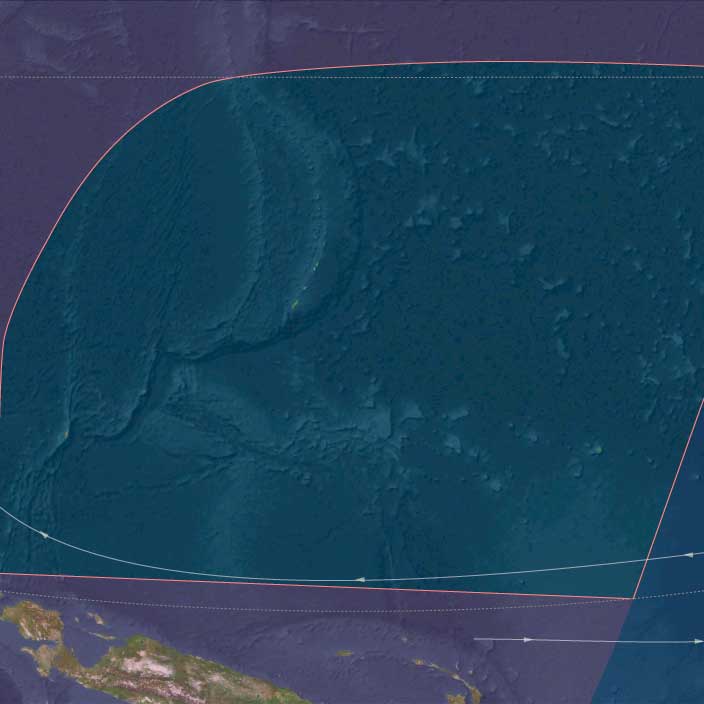

Across the northwestern Pacific, a constellation of small islands and coral atolls—scattered across millions of square kilometers—formed one of humanity’s most intricate maritime environments.

In this early first-millennium epoch, Micronesia was not a single polity but an archipelagic system of localized stability and long-distance communication.

Communities in the east refined life upon fragile atolls through arboriculture, lagoon management, and navigational mastery; those in the west built wet-taro fields, stone fish traps, and canoe networks that tied high islands to far-flung reefs.

Together they composed an oceanic order of balance, reciprocity, and movement: a society not bounded by land but measured by the knowledge of distance.

Geography and Environment

Micronesia arcs between the tropic lines, divided by ecological type into two main subregions.

The eastern chains—Kiribati, the Marshalls, Nauru, and Kosrae—are atoll and low-island worlds: rings of coral enclosing turquoise lagoons, their soils thin and water lenses delicate.

The western arc—the Marianas, Palau, and Yap with its outer atolls—includes both volcanic highlands and uplifted limestone plateaus fringed by rich reefs.

Prevailing trade winds and steady ocean swells unified the region, their seasonal rhythms setting the tempo of planting, sailing, and exchange.

ENSO variability occasionally brought droughts that tested atoll sustainability; yet Micronesian societies turned vulnerability into virtuosity, inventing ecological and social mechanisms for enduring scarcity.

Societies and Political Development

Eastern Micronesia

By the mid-first millennium CE, the atolls of Kiribati and the Marshalls supported well-ordered village polities centered on communal meeting houses (maneaba) and hereditary lineage stewards.

Societies were decentralized but cohesive: social rank derived from kinship, maritime skill, and the ritual redistribution of preserved foods.

On the high, fertile island of Kosrae, valleys supported irrigated taro ponds and emerging sacred kingship (tokosra), a pattern that would blossom into monumental architecture in later centuries.

The atolls, by contrast, prized consensus and survival over hierarchy—each islet functioning as both home and storehouse within a larger archipelagic circuit.

Western Micronesia

In Palau and Yap, taro-swamp engineering and elaborate clan systems underpinned village confederacies.

Chiefly councils managed irrigation, fishing zones, and ceremonial exchange, producing a stable maritime agrarian balance.

Across the Marianas, early latte-house foundations marked a transition toward monumental architecture, while on Yap, ritual tribute networks with the outer atolls—later known as the sawei system—took early shape, binding distant islands in cycles of mutual aid and prestige.

Economy and Exchange

Micronesian economies rested on diversified arboriculture and controlled redundancy.

On atolls, breadfruit, pandanus, and coconut formed the perennial canopy; swamp taro (babai) in excavated pits ensured starch security.

Kosrae and Yap’s river-fed wetlands yielded high crop surpluses, exchanged for reef products and shell valuables.

Across the region, fishing—reef, lagoon, and deep-sea—was both subsistence and ceremony: bait lines, trolling, and weirs harvested the sea’s vertical layers.

Inter-island trade moved preserved breadfruit paste, fine mats, cordage, timber, and shell ornaments.

Shell valuables (e.g., rai stones’ prototypes on Yap, armbands in the Marshalls) were less currency than covenant—tokens of alliance, ritual, and story.

Canoe-building was itself an industry of cooperation: outer islands sent shell tools and fibers to high islands for hull timber and resins, embodying the principle of exchange as survival.

Technology and Material Culture

Canoe architecture reached high refinement.

Outrigger and double-hulled forms combined lightness and resilience; lashings of coconut fiber, sealed with breadfruit sap, produced hulls capable of inter-archipelagic voyages.

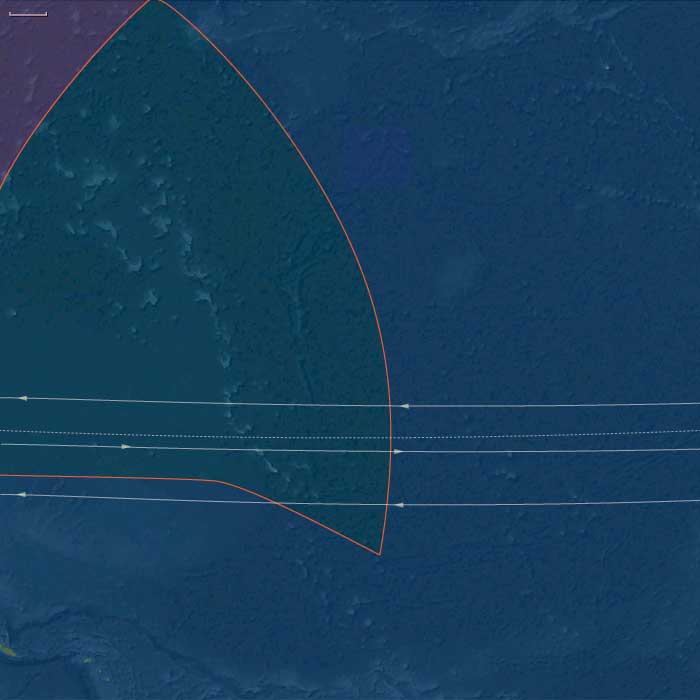

The crab-claw sail harnessed both headwind tacking and downwind runs; navigation depended on stars, wave patterns, clouds, and seabird flight.

In the Marshalls, stick charts (rebbelib, meddo) encoded this information as memory maps—graceful wooden geometries representing the curvature of swells and island chains.

Pottery faded from use; woven mats, shell tools, and fiber craft defined daily life.

Maneaba meeting houses and bai (Palau council halls) stood as architectural expressions of cosmology—roof trusses and beams mirroring the celestial order of islands and stars.

Belief and Symbolism

Ancestral spirits governed wind, fish, and fertility.

Each clan traced descent from mythic voyagers or island-creating deities, grounding identity in both ocean and land.

Navigators held sacred rank; their knowledge of stars and swells was protected by ritual observances and initiation.

Ceremonial feasts reaffirmed reciprocity; song and dance rehearsed cosmology and navigation simultaneously.

Across Micronesia, the canoe itself was cosmic model—its hull the world, its mast the axis between sea and sky, its sail the breath of creation.

Adaptation and Resilience

Micronesian survival depended on redundancy, reciprocity, and recordkeeping.

Households spread resources across multiple islets, ensuring that cyclones or droughts on one could be offset by another’s bounty.

Preservation of breadfruit and fish provided long-term stores; exchange networks redistributed wealth and food after storms.

Social protocols of hospitality turned mobility into insurance: a guest was never a stranger but a partner in the continuum of voyaging kin.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 819 CE, Micronesia had achieved a stable and sophisticated equilibrium between ecology and exchange.

Its two spheres—East Micronesia’s atoll commons and West Micronesia’s high-island hierarchies—formed a balanced duality: one democratic and dispersed, the other structured and monumental.

Together they created a resilient maritime civilization, every island both node and compass point in a larger design.

This early system anticipated the monumental age to come: the stone cities of Lelu and Nan Madol, the latte pillars of the Marianas, and the full flowering of the sawei network on Yap.

Yet even in its beginnings, Micronesia demonstrates why regional history must be read through its subregions: the ocean itself demanded variety, and the archipelago’s unity lay not in uniformity but in the mathematics of difference — a geometry of survival traced upon the sea.