Micronesia (820 – 963 CE): Atoll Adaptations, …

Years: 820 - 963

Micronesia (820 – 963 CE): Atoll Adaptations, Sacred Kingship, and the Ocean of Exchange

Geographic and Environmental Context

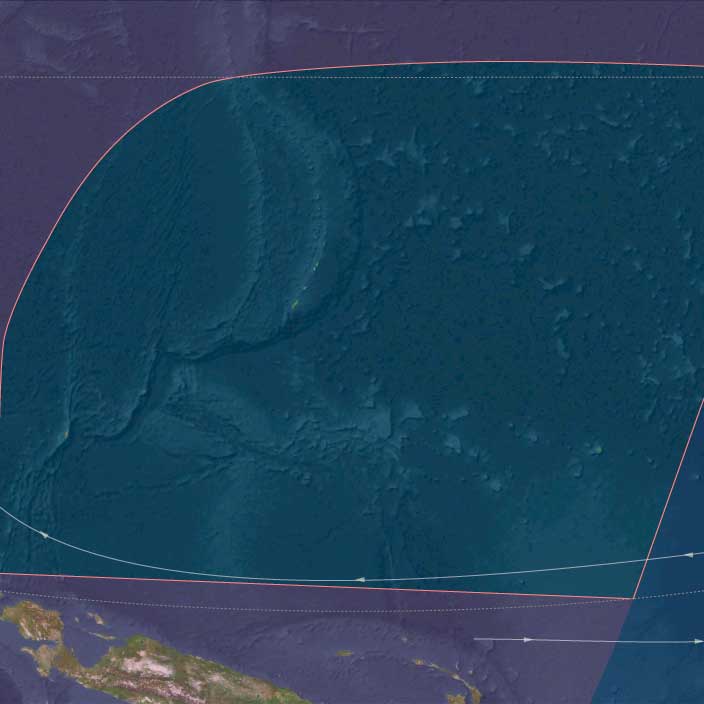

Micronesia in this age stretched across thousands of kilometers of the western Pacific, a constellation of coral atolls and volcanic peaks lying between the equator and the tropic lines.

It embraced two broad zones:

-

West Micronesia — the Mariana Islands, Yap, Palau, Chuuk, and their surrounding atolls — high volcanic islands and lagoon systems forming the core of early political hierarchies.

-

East Micronesia — the Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, and the high island of Kosrae — a vast field of atoll chains and single peaks where communities perfected arboriculture, water-lens management, and long-range navigation.

Across both regions, communities transformed fragile maritime environments into stable cultural seascapes, balancing horticulture, reef fisheries, and ritualized exchange.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The centuries between 820 and 963 CE brought generally warm, stable tropical conditions, though subject to ENSO-driven droughts and occasional typhoons.

-

Atolls endured episodic stress on water lenses and breadfruit groves, mitigated by arboriculture and preserved food stores.

-

High islands such as Kosrae, Yap, and Palau buffered shortages with orographic rainfall and permanent streams.

-

Across the archipelagos, ocean currents and trade-wind predictability allowed continuous voyaging, even during lean years.

Micronesia’s ecological equilibrium rested on the rhythm of sea, wind, and communal preparedness.

Societies and Political Developments

West Micronesia: Prestige Centers and Voyaging Networks

-

Yap emerged as a ritual and economic magnet, its chiefs (later gatchaper) forging hierarchical alliances with outer atolls through early forms of the sawei system. Outer islands provided preserved breadfruit, mats, and shells, receiving timber, turmeric, and prestige stones in return.

-

Chuuk Lagoon organized dense volcanic-island chiefdoms under clan leadership, combining horticulture with lagoon fishing and fortified refuges for defense.

-

Palau’s councils of chiefs governed taro-swamp agriculture and lagoon tenure, resolving disputes through ritual and warfare.

-

In the Marianas, the appearance of latte-stone house foundations marked rising chiefly hierarchy; ancestral lines (maga’låhi) consolidated authority through megalithic architecture.

-

The outer Carolinian atolls maintained autonomy but oriented ritual and tribute ties toward Yap’s prestige sphere.

East Micronesia: Atoll Confederacies and Sacred Kingship

-

In the Marshalls, a tripartite social structure of iroij (paramounts), alab (land stewards), and rijerbal (workers) governed atoll society through lineage and reef tenure.

-

Kiribati (Gilbert Islands) centered life in the maneaba, the communal meeting house where elders mediated access to land, water, and fishing grounds.

-

Nauru sustained small clan communities based on reef and nearshore fisheries, supplementing limited gardens with exchange to passing canoes.

-

On the volcanic high island of Kosrae, reliable water and forest surpluses fostered the first stirrings of centralized kingship (tokosra). Ritual leaders presided over first-fruit ceremonies and temple feasts, precursors to the monumental Lelu court of later centuries.

Economy and Trade

Micronesia’s economy revolved around diversity, storage, and exchange.

-

Horticulture and arboriculture: taro (wet and dry), yam, breadfruit, coconut, and pandanus formed the dietary backbone; swamp-taro pits (babai) safeguarded food through drought.

-

Fisheries: lagoon and deep-sea fishing, shellfish collecting, and turtle hunting ensured protein security.

-

Preservation and storage: fermented breadfruit, dried fish, and pandanus paste sustained communities through cyclone and El Niño cycles.

-

Inter-island exchange:

-

Atoll goods (shells, mats, sennit cordage, dried foods) moved to high islands for timber and stone.

-

Yap’s sawei and Kosrae’s trade sphere bound outer islands to ritual centers.

-

Voyaging networks interlaced West and East Micronesia, extending from the Philippines to the Marshalls.

-

Subsistence and Technology

-

Water management: lined and composted taro pits, carefully placed wells, and grove mulching protected fragile freshwater lenses.

-

Canoe-building: breadfruit and mahogany hulls, lashed with coconut fiber; outrigger or double-hulled designs with crab-claw or triangular sails; atoll canoes were lightweight and swift, high-island craft sturdy for cargo.

-

Navigation: wayfinding through star compasses, ocean swells, seabird routes, and in the Marshalls, stick charts (rebbelib, meddo) modeling wave interactions.

-

Architecture: maneaba and bai (Palau meeting houses) served as both civic and ritual centers; latte-stone platforms in the Marianas elevated houses and shrines above coastal floods.

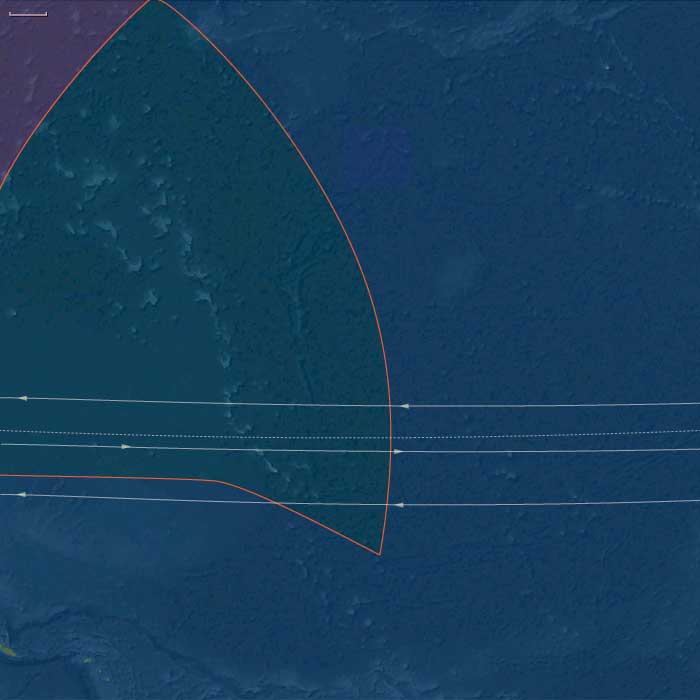

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Sawei routes radiated from Yap to Ulithi, Woleai, Lamotrek, and Satawal, structuring periodic tribute voyages.

-

Ralik–Ratak channels joined Marshall atolls into a coherent political ecology.

-

Kosrae served as an eastern hub linking high-island and atoll economies, dispatching food and craft goods in exchange for shells and ornaments.

-

Kiribati and Nauru tied into broader Gilbert–Marshall sailing circuits; Palau and Chuuk reached westward toward the Philippines and eastward toward the Carolines.

These routes made Micronesia an oceanic commons, sustained by obligation, reciprocity, and shared wayfinding knowledge.

Belief and Symbolism

Micronesian spirituality merged ancestral power, sea cosmology, and navigational ritual.

-

In Kiribati, the maneaba embodied both civic governance and sacred genealogy.

-

In the Marshalls, chiefs traced descent from founding navigators and land-spirit ancestors.

-

Kosrae’s early kingship fused divine sanction with agricultural fertility; rituals of first-fruits and canoe consecration unified people and place.

-

Across the Carolines, voyaging chants preserved sacred geography; in Palau, monumental bai meeting houses displayed carved mythic motifs connecting taro swamps to the spirit world.

-

Yap’s stone shrines and Marianas’ latte stones anchored ancestry in enduring materials.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Multi-island subsistence portfolios buffered risk: high islands exported timber and taro; atolls supplied dried fish, coconut, and mats.

-

Preservation and storage mitigated ENSO droughts.

-

Voyaging alliances redistributed food after cyclones or crop loss.

-

Ritual redistribution through tribute and feasting balanced wealth and prestige, reinforcing ecological cooperation.

-

Tenure flexibility—rotating land and reef use—allowed renewal of fragile environments.

Micronesian resilience rested on mobility, reciprocity, and reverence for the sea.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, Micronesia had become a maritime commonwealth of integrated yet diverse societies:

-

Yap commanded a radiating prestige sphere through early sawei tribute.

-

Kosrae rose as a sacred polity presaging later monumental rule.

-

Marianas, Palau, and Chuuk established enduring architectural and political forms.

-

Kiribati and the Marshalls refined atoll arboriculture and navigation into an art of survival.

Together, these islands forged one of humanity’s most resilient oceanic civilizations—a world where star paths, breadfruit groves, and reef channels formed the arteries of life and law, linking scattered atolls into a single, voyaging society.