Micronesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene …

Years: 7821BCE - 6094BCE

Micronesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Reef Stability, Freshwater Lenses, and Islands in Formation

Geographic & Environmental Context

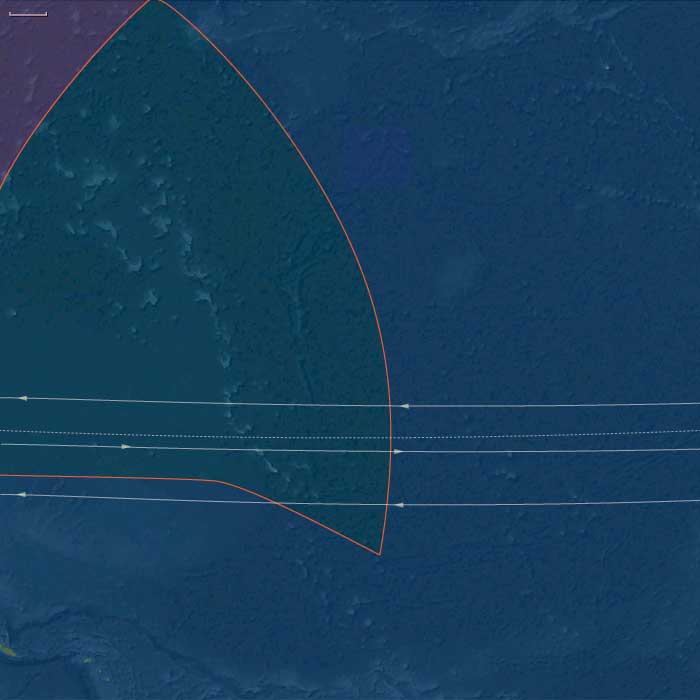

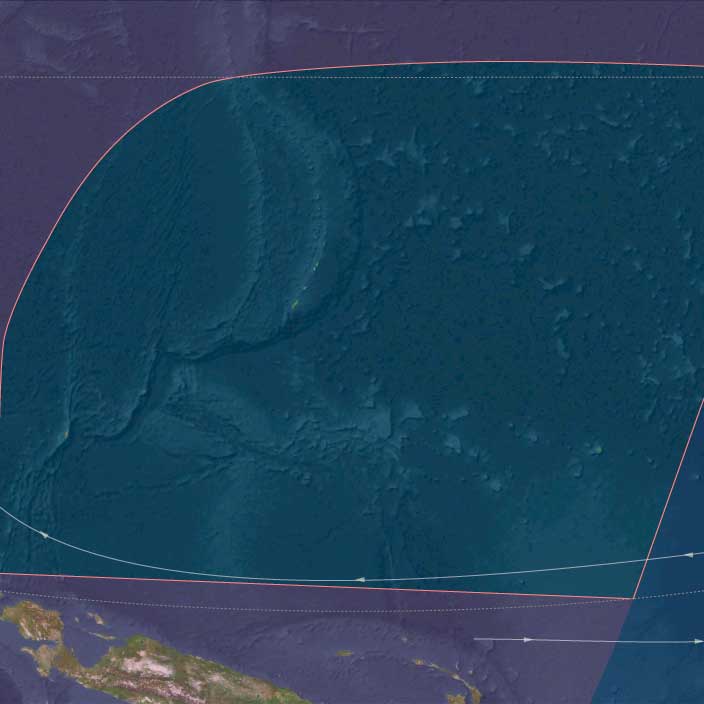

During the Early Holocene, Micronesia—a vast constellation of atolls, raised limestone islands, and volcanic high islands—was still settling into its modern geography.

Rising postglacial seas transformed once-emergent platforms into lagoons, reef arcs, and perched freshwater systems.

Two principal environmental spheres defined the region:

-

West Micronesia, including the Marianas, Palau, and Yap groups, where volcanic and limestone islands anchored extensive fringing reefs and early mangrove belts.

-

East Micronesia, encompassing the Gilberts, Marshalls, Nauru, and Kosrae, where reef–lagoon systems matured into stable atoll chains and freshwater lenses developed beneath them.

This was a time before human arrival, when wind, coral, and rainfall were the master engineers.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal optimum brought warmer sea-surface temperatures, steady trade winds, and reliable monsoon rainfall.

Sea level rose slowly toward its mid-Holocene highstand, submerging reef flats and stabilizing lagoon hydrology.

-

Atolls became fully enclosed systems with perched freshwater lenses, fed by rainfall infiltration and sealed by the porosity of coral sand.

-

High islands like Kosrae and Palau developed complex ridge-to-reef watersheds, with perennial streams delivering sediment and nutrients to lagoon nurseries.

Occasional storm events reworked coastal dunes, forming sabkha pockets and back-pond wetlands, but the broader climatic regime remained calm and predictable.

Baseline Ecology (Before Human Presence)

Micronesia’s ecological architecture reached a mature prehuman balance:

-

Atolls: newly consolidated lagoons teemed with coral, mollusks, and crustaceans. Lens-fed wetlands and brackish depressions behind ridges supported sedges, mangroves, and salt-tolerant grasses.

-

High islands (Palau, Kosrae): dense cloud forests and riparian corridors developed on volcanic slopes; rivers carved ravines that merged with reef-fringed estuaries.

-

Mangrove–reef coupling: decaying leaf litter and root detritus fertilized lagoon systems, feeding crabs, mollusks, and juvenile fish.

-

Seabirds nested along rocky headlands and outer islets, their guano linking ocean and land nutrient cycles.

These ecosystems functioned as closed hydrological loops—each island a miniature, self-regulating world.

Geomorphic and Hydrological Processes

As sea level stabilized, hydrology became the key ecological force:

-

Freshwater lenses, suspended above saltwater tables, expanded beneath coral islands, storing rainfall for future wells and taro pits.

-

Sediment accretion from storm reworking built natural ridges that enclosed lagoons.

-

Reef crests diversified into spur-and-groove systems, buffering waves and promoting lagoon calm.

-

Mangrove colonization anchored coastlines, consolidating organic soils and trapping fine sediments.

By 6,000 BCE, these systems had reached quasi-modern stability, setting the stage for eventual human adaptation to each hydrological niche.

Regional Profiles

-

West Micronesia (Marianas, Palau, Yap):

The Marianas’ limestone plateaus supported early lens wetlands, while Palau’s volcanic core and Rock Islands lagoon delivered sediment to mangroves and coral flats. Yap’s raised reef islands paired coastal marshes with outer atoll fisheries, creating natural templates for later garden–reef economies. -

East Micronesia (Gilberts, Marshalls, Nauru, Kosrae):

On the atolls, broad freshwater lenses and back-lagoon wetlands developed under steady rainfall. Nauru’s uplifted phosphate terrain held pockets of shallow groundwater. Kosrae, a high volcanic island on the eastern Caroline arc, became a hydrological hub, its clear perennial streams anticipating the wet-field taro cultivation of later millennia.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Without humans, ecosystems self-tuned through hydrological feedbacks:

-

Rainfall infiltration and coral permeability balanced freshwater and saltwater mixing.

-

Mangroves and beach vegetation stabilized ridges and protected lenses from salinity intrusion.

-

Coral accretion kept reef surfaces aligned with sea-level rise, preventing lagoon stagnation.

-

Guano enrichment enhanced terrestrial productivity, fertilizing sparse atoll soils.

These processes collectively forged the resilient ecological foundations that would later sustain Micronesian agriculture and navigation.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Micronesia had entered its Holocene ecological maturity.

Across thousands of kilometers of ocean, atolls and high islands had stabilized into enduring hydrological systems: freshwater lenses, mangrove belts, lagoon reefs, and volcanic watersheds.

These natural formations would become the infrastructure for future human settlement—the freshwater wells, taro pits, and canoe channels of later island cultures.

The Early Holocene was thus an age of silent preparation, when wind, wave, and coral sculpted the stage on which the later seafaring societies of Micronesia would thrive.