Micronesia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene …

Years: 6093BCE - 4366BCE

Micronesia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Reef Highstands and the Formation of Island Worlds

Geographic & Environmental Context

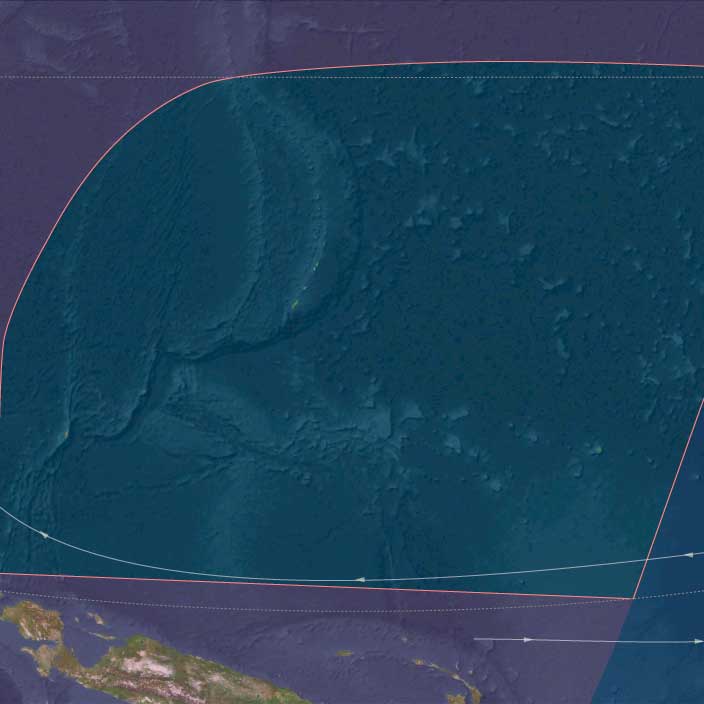

During the Middle Holocene, Micronesia—a vast expanse of atolls, high volcanic islands, and raised limestone platforms scattered across the western and central Pacific—was shaped by rising seas and stabilizing reefs.

The region’s two great arcs—West Micronesia (Marianas, Palau, Yap and its outer atolls) and East Micronesia (Marshall Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, and Kosrae)—were joined by shared geomorphic and oceanic processes.

A global Hypsithermal highstand lifted sea levels slightly above modern, flooding reef flats and broadening lagoons.

-

In the Marianas and Yap–Palau corridor, limestone terraces and volcanic uplands framed newly expanded back-reef wetlands and sand spits.

-

In the Gilberts and Marshalls, atoll rims stabilized into continuous coral arcs enclosing calm inner lagoons.

-

On Nauru and Kosrae, interior depressions and river mouths developed freshwater and estuarine niches.

These transformations produced the modern outlines of reef, lagoon, and pass that would later sustain some of the world’s most sophisticated oceanic societies.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm phase brought warm, humid stability moderated by the vast Pacific’s thermal inertia.

ENSO oscillations existed but were weaker than in later millennia, bringing occasional dry intervals followed by abundant rains.

Cyclones struck episodically, reworking beaches and passes but rarely causing long-term change. The constancy of the trade-wind regime kept the region’s climate predictable, with gentle alternations between wet and dry seasons.

This steadiness allowed reefs to accrete vertically and horizontally, keeping pace with sea-level rise and forming complex lagoonal systems that approached their modern configuration.

Baseline Ecology (Before Human Arrival)

These were fully mature marine landscapes without human presence, yet biologically vibrant and self-regulating.

-

Atoll lagoons supported dense fish and invertebrate populations: parrotfish, wrasses, giant clams, and crabs filled reef crests and channels.

-

Mangrove and pandanus forests stabilized leeward rims and shore ridges, fixing sediments and nurturing brackish nurseries.

-

Kosrae’s rivers and estuaries hosted prawns, gobies, and mullet; Nauru’s karst hollows accumulated rainwater and supported freshwater crustaceans.

-

Seabirds and turtles nested in abundance, transferring marine nutrients ashore and fertilizing coastal vegetation.

-

Offshore, rich planktonic productivity sustained tuna and other pelagic species that later generations would harvest by sail and line.

Ecological succession had achieved ridge-to-reef balance—a complete, resilient system awaiting the first human voyagers.

Geomorphological Development

The mid-Holocene highstand sculpted Micronesia’s enduring geography.

Back-reef lagoons deepened and stabilized, sand cays coalesced into permanent islands, and mangroves colonized new shorelines.

Reef passes matured into stable tidal channels, establishing the hydraulic pattern that would later guide canoe passages, fish weirs, and anchorage basins.

In uplifted zones such as Guam and Yap, coastal terraces and shallow soils formed over ancient coral limestone, providing the first terrestrial frameworks for future agriculture.

This was the foundational moment when Micronesia’s ecological architecture—the template of its islands and reefs—became fixed.

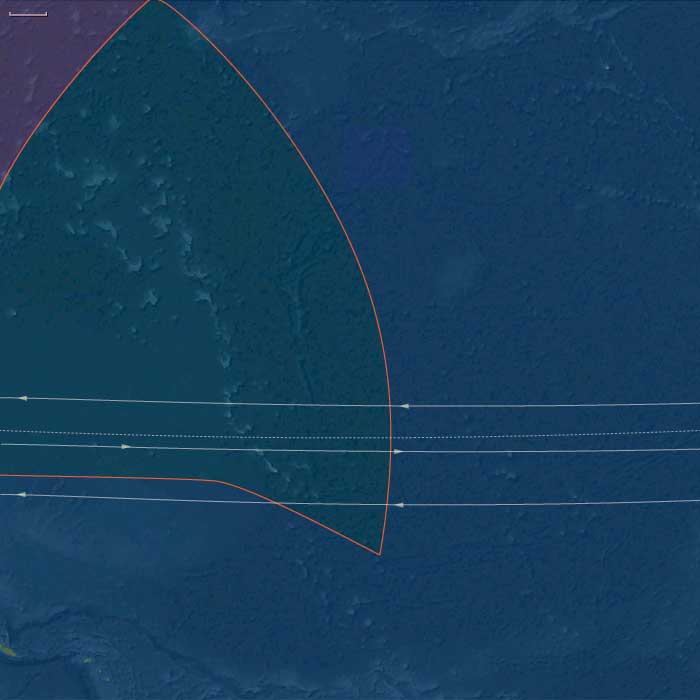

Movement & Interaction Corridors (Natural, Not Human)

Though humans had not yet reached the region, ocean currents and migratory species created natural corridors of connection.

The North and South Equatorial Currents swept east–west across the atoll chains, redistributing coral larvae, seeds, and driftwood.

Seabird flyways and turtle migrations linked Micronesia with Melanesia and Polynesia, forming a living biological network that prefigured later maritime exchange routes.

These natural patterns of flow and renewal would become, millennia later, the “invisible maps” followed by Micronesian navigators tracing the same corridors by sail and star.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Micronesia’s ecosystems thrived through redundancy and regeneration.

Coral communities diversified with every disturbance, recolonizing storm-damaged zones within years. Mangroves advanced along sedimented inlets, protecting lagoon margins.

Seabirds shifted colonies as sand cays formed or eroded, maintaining species continuity across the archipelagos.

The equilibrium between oceanic productivity and terrestrial colonization produced one of the most resilient ecological systems on Earth, capable of self-repair across millennia of climatic fluctuation.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Micronesia stood as a fully realized oceanic ecosystem, its reefs, lagoons, and high islands sculpted into the forms still visible today.

Though uninhabited, the region’s landscapes—reef passes, atoll ponds, freshwater lenses, and mangrove-lined bays—had reached the precise configuration that would later support canoe navigation, aquaculture, and sustainable atoll agriculture.

The enduring lesson of this epoch is one of natural preparation: the sea and coral had already built the infrastructure of life, awaiting the arrival of navigators who would transform these biological corridors into highways of culture.