Micronesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

Micronesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Rising Seas, Reef Builders, and Islands Beyond Human Reach

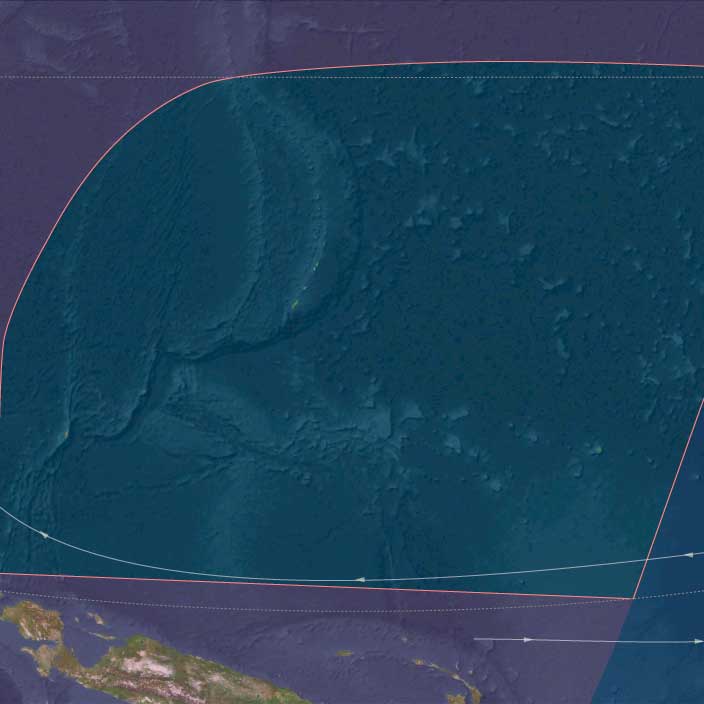

Geographic & Environmental Context

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Micronesia—spanning the Marianas, Palau, Yap, the Caroline arc, and the Gilberts and Marshalls—was a vast expanse of reefs and islands slowly emerging into their modern form.

At the Last Glacial Maximum (26,500–19,000 BCE), sea levels lay more than 100 m below present, enlarging volcanic islands and exposing broad limestone terraces across the Marianas and Yap. As global ice sheets melted, rising seas drowned coastal shelves, carved lagoon passes, and transformed former uplands into rings of atolls and reef-rimmed embayments.

By the end of this period, Micronesia’s archipelagic geometry—chains of high volcanic islands interlaced with low coral platforms—had taken shape, but it remained entirely beyond human knowledge or navigation.

-

West Micronesia: the Marianas, Palau, and Yap, a mix of volcanic high islands, raised limestone plateaus, and emerging atolls.

-

East Micronesia: the Gilberts (Kiribati), Marshalls (Ralik–Ratak), Nauru, and Kosrae, where low coral plains and volcanic headlands framed nascent lagoons.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Across these millennia, Micronesia oscillated between glacial austerity and interglacial abundance:

-

Last Glacial Maximum: cooler seas and weaker monsoons lowered rainfall and slowed coral accretion; broad coastal plains expanded on high islands.

-

Bølling–Allerød warming (14,700–12,900 BCE): warmer seas and renewed precipitation revived reefs and forests; lagoons deepened.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): a short cooling pulse reduced coral growth rates but had limited ecological disruption.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): warming stabilized, and coral “catch-up” growth filled drowned basins with vibrant reef life.

By 7,800 BCE, the modern climatic regime of steady trades, wet monsoons, and stable sea temperatures was established.

Flora, Fauna, and Baseline Ecology

Without human disturbance, Micronesia’s ecosystems thrived in pristine isolation:

-

High islands (Marianas, Palau, Kosrae) supported dense tropical rainforests—palms, hardwoods, tree ferns, and lianas—enclosing fertile volcanic soils.

-

Low coral islands (Marshalls, Gilberts, Yap outer arc) bore salt-tolerant scrub, pandanus, and grasses stabilized by guano-enriched sands.

-

Lagoons and reefs teemed with parrotfish, surgeonfish, mullet, turtles, and reef invertebrates; seabird colonies nested on rocky headlands.

-

Nauru’s uplifted limestone retained small freshwater pockets sustaining hardy shrubs and seabird rookeries.

-

Estuaries of Kosrae and Palau formed wetlands fed by volcanic runoff—hubs of biodiversity that would one day support human wet-field cultivation.

Geomorphic and Oceanic Dynamics

The transformation from continental shelves to island reefs defined Micronesia’s emergence:

-

Rapid deglacial sea-level rise flooded glacial terraces, producing lagoonal amphitheaters and pass channelsstill visible today in the Marshalls and Gilberts.

-

Reefs “caught up” to the rising sea, accreting vertically to preserve light access.

-

Volcanic activity in the Marianas arc renewed soils and reshaped coasts.

-

Cyclones and monsoon floods reworked beaches, continually redistributing sediments and forming the foundations of future atoll chains.

Through these processes, Micronesia’s reef–lagoon–islet system reached near-modern configuration long before any human sails appeared on the horizon.

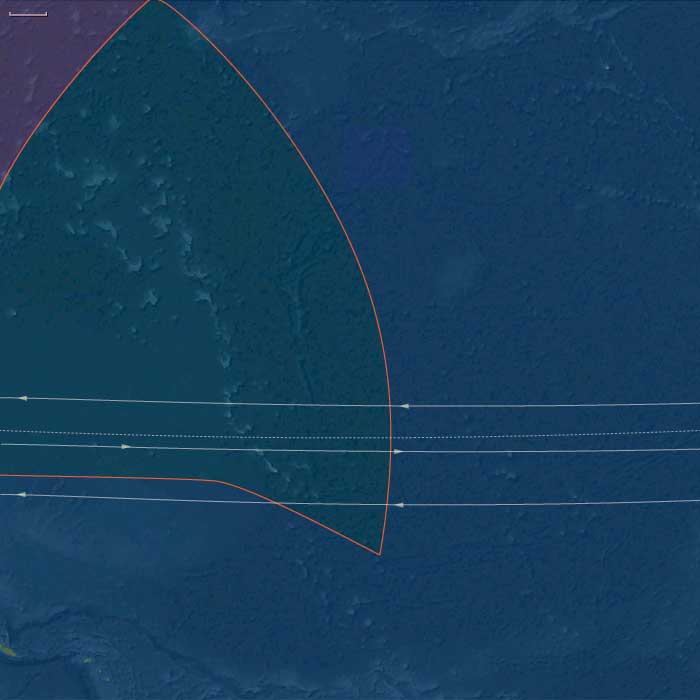

Movement & Interaction Corridors

No human networks yet crossed this oceanic space.

Instead, natural circulations dominated:

-

The North Equatorial Current and its Countercurrent sculpted nutrient flows across the Caroline arc.

-

Migratory seabirds and turtles traced seasonal loops from the Philippines and Melanesia to Micronesian rookeries.

-

Driftwood, seeds, and pumice arrived via the Kuroshio and equatorial gyres, seeding plant life on newly formed cays.

In this epoch, wind and wave were the only navigators, the ocean itself the sole agent of exchange.

Symbolic and Conceptual Role

To late Pleistocene humans living along the western Pacific rim, Micronesia lay entirely beyond the conceivable horizon—neither seen nor imagined.

These island chains, thousands of kilometers from the nearest continental coast, existed only as natural monuments to isolation—the unvisited heart of the Pacific that would, much later, become the ocean’s crossroads.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Ecosystems displayed profound resilience:

-

Coral growth kept pace with rapid sea-level rise, preventing reef drowning.

-

Vegetation succession—first grasses and herbs, then palms and forests—stabilized soils and buffered erosion.

-

Seabird and turtle migrations maintained nutrient loops between ocean and land.

-

Lagoon sediments trapped organics, forming the fertile substrates that would one day support human gardening and settlement.

Micronesia emerged from deglaciation as a self-renewing biological network, balanced between storm energy and coral productivity.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Micronesia had reached ecological maturity.

Its reefs, lagoons, and volcanic highlands had stabilized into recognizable modern systems, with thriving biota and complex nutrient webs.

No humans yet crossed these waters, but the oceanic geography—chains of atolls spaced within sightlines, reefs protecting calm lagoons, dependable currents and winds—was complete.

The stage was set for the future age of voyagers: when humans finally arrived millennia later, they would find a world already perfectly tuned to sustain maritime civilization.