Micronesia (2637 – 910 BCE): Island Pioneers, …

Years: 2637BCE - 910BCE

Micronesia (2637 – 910 BCE): Island Pioneers, Canoe Networks, and the First Oceanic Web

Regional Overview

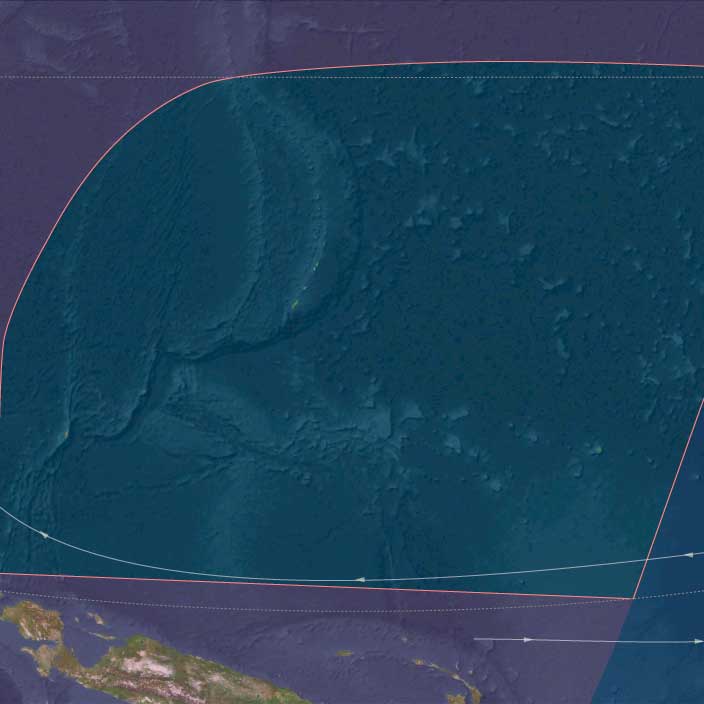

Across the western Pacific’s equatorial arc, Micronesia emerged as one of humanity’s earliest experiments in life on the open ocean.

Here, voyagers from Island Southeast Asia and the western Pacific littoral established the first permanent settlements on chains of atolls and high islands scattered across millions of square kilometers of sea.

By the early first millennium BCE, Marianas, Palau, Yap, Kiribati, the Marshalls, and Kosrae had become nodes in an expanding lattice of navigation, arboriculture, and exchange—each settlement a self-contained world, yet connected by routes of memory and stars.

Geography and Environment

Micronesia’s fragmented geography—coral atolls, uplifted limestone islands, and volcanic highlands—produced one of the planet’s most diverse maritime landscapes.

The Marianas formed the northern anchor, their volcanic soils rich but their freshwater lenses fragile.

To the south and west, the Caroline arc (Palau, Yap, Kosrae) offered volcanic relief, streams, and mangrove belts, while the Gilbert and Marshall chains stretched across the equator as low coral platforms enclosing vast lagoons.

Every environment demanded different balances of arboriculture, lagoon fishing, and rainwater harvesting.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The late Holocene climate was generally warm and stable, punctuated by ENSO oscillations that alternated drought and storm.

These cycles shaped migration, trade, and settlement spacing: atoll dwellers developed meticulous rain-catch systems and food storage to survive dry years, while high-island communities used perennial streams and valley gardens as drought refuges.

Regional variation—humid Kosrae versus arid Kiribati—encouraged ecological complementarity and exchange.

Societies and Settlement

By the mid–second millennium BCE, seafaring Austronesians had founded the Marianas, among the first islands settled beyond Near Oceania.

Their descendants established coastal hamlets, cultivated taro and breadfruit, and maintained lagoon fisheries.

In Palau and Yap, settlement followed soon after, with hamlets clustering near freshwater lenses and mangrove channels.

Eastward, settlers reached the Marshalls, Gilberts, and Kosrae, planting breadfruit and pandanus, digging swamp-taro pits, and building stilt houses at lagoon edges.

Each island or atoll became both home and harbor—a managed ecosystem engineered through arboriculture and kinship.

Economy and Technology

Micronesian economies combined tree-crop horticulture, taro cultivation, and lagoon fishing within a framework of regional trade.

Communities managed transported landscapes: coconut, breadfruit, pandanus, and taro formed the nutritional base, supplemented by turtles, fish, and shellfish.

Outrigger canoes with crab-claw sails were the principal instruments of survival, mobility, and prestige.

Shell and stone adzes, drilled fishhooks, and early tidal fish weirs reflected technological ingenuity in scarce-resource environments.

These tools, alongside elaborate knowledge of stars, swells, and cloud formations, allowed sustained navigation between islands separated by hundreds of kilometers.

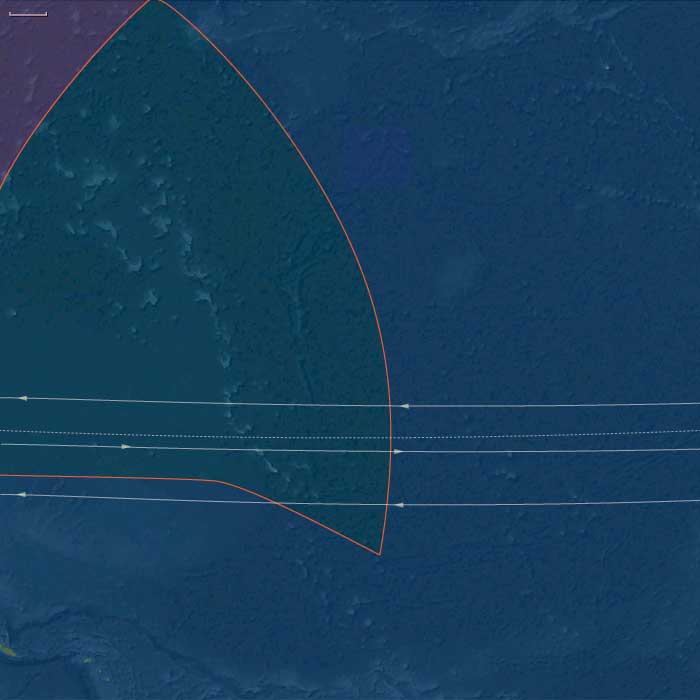

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Voyaging corridors knit the subregion into an interlinked sea.

The Ralik–Ratak pairs in the Marshalls functioned as dual atoll systems, while the Gilbert chain operated as a north–south shuttle route.

Palau connected mangrove-rich high islands with limestone islets and coral shoals, exchanging shell tools and forest products.

Yap, emerging as a high-island hub, began to organize reciprocal relationships with its outer atolls—precursors of the later sawei system.

Farther east, Kosrae linked into Carolinian navigation networks, transmitting canoe forms and ceremonial knowledge across thousands of kilometers.

Belief and Symbolism

Micronesian spirituality fused land, lineage, and sea.

Ancestral shrines stood beneath breadfruit trees or beside canoe landings, marking first clearings and founding voyages.

Navigators invoked deities of wind and swell, while ritual plantings of the first breadfruit reaffirmed both genealogical rights and ecological balance.

Canoe construction, launching, and voyaging were sacred acts governed by ritual taboos that linked every island to its mythical origin.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Micronesian communities achieved remarkable ecological equilibrium.

Atoll dwellers sustained themselves on a narrow base of freshwater and soil by integrating arboriculture, lagoon ecology, and social reciprocity.

Islet zoning—separating gardens, wells, canoe yards, and burial sites—optimized space and protected resources.

Food preservation (dried breadfruit, fermented pandanus, smoked fish) buffered households against climate swings.

Inter-island kinship networks allowed redistribution after cyclones or droughts, ensuring collective survival.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 910 BCE, Micronesia had become a maritime commonwealth of small islands woven together by voyaging, arboriculture, and memory.

Its inhabitants had mastered navigation without metal, sustainability without surplus, and connection without empire—a model of balance across one of the planet’s most dispersed archipelagos.

This network of pioneers provided the ecological, technical, and cultural foundation for the monumental navigation and stone-architecture traditions that would later define the Carolines, the Marshalls, and the Micronesian high-island capitals of the medieval centuries.