East Micronesia (1828–1971 CE) Atolls under …

Years: 1828 - 1971

East Micronesia (1828–1971 CE)

Atolls under Empire, Nuclear Shadows, and Independence Movements

Geography & Environmental Context

East Micronesia includes the Marshall Islands, Kiribati (Gilbert Islands), and parts of eastern Caroline Islands. Anchors include the low coral atolls of Bikini, Enewetak, Tarawa, Majuro, and volcanic outliers in eastern Carolines. These fragile islands depended on thin soils, freshwater lenses, and reef resources.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Equatorial sun, trade winds, and seasonal rains sustained coconut groves, taro pits, and breadfruit trees. Typhoons and droughts threatened atolls. Rising copra demand in the 19th century reshaped land use. From 1946, nuclear testing at Bikini and Enewetak devastated environments, displacing communities and contaminating ecosystems.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Traditional: Fishing, taro pits, breadfruit fermentation, and coconut cultivation sustained households. Canoes linked atolls for exchange.

-

Colonial economies: Copra plantations dominated under German, British, and later Japanese administration.

-

20th century: Japanese rule (1914–1944) militarized atolls, introducing schools, sugar works, and garrisons. Postwar U.S. trusteeship shifted subsistence economies toward aid dependence.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Sailing canoes remained crucial into the 20th century; missions introduced literacy and hymnals.

-

Japanese rule: Concrete bunkers, ports, and airstrips built in the Marshalls and Gilberts.

-

U.S. era: Nuclear facilities at Bikini and Enewetak, military airfields (Kwajalein), and weather stations. Radios, sewing machines, and prefabricated housing spread after WWII.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

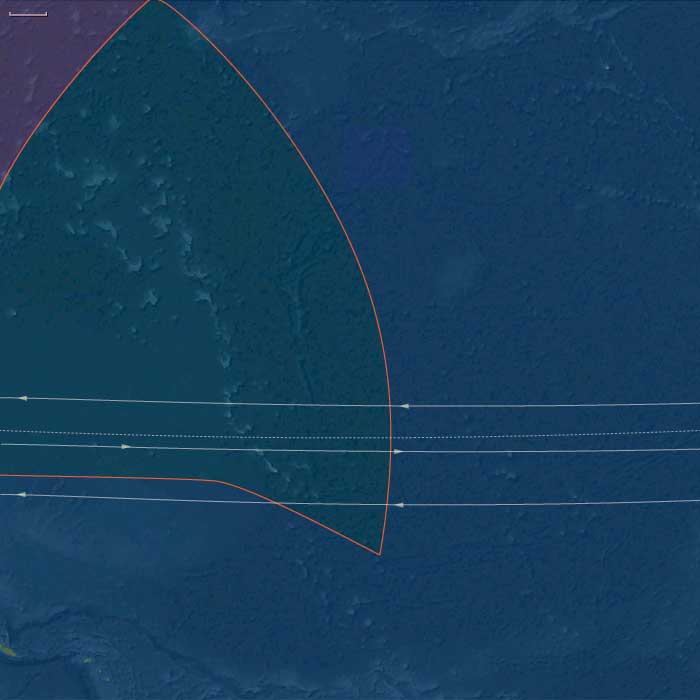

Colonial transfers: Spanish ceded Carolines and Marshalls to Germany (1899); Japan occupied after 1914; U.S. assumed control in 1947 under UN trusteeship.

-

War: Marshall and Gilbert atolls (Tarawa, Kwajalein) saw decisive WWII battles.

-

Displacement: Bikini and Enewetak islanders were relocated multiple times for U.S. nuclear testing.

-

Migration: Islanders began moving to Guam, Hawaii, and mainland U.S. under trust-era migration programs.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Religion: Catholic and Protestant missions reshaped ritual life; Christianity fused with atoll traditions.

-

Oral traditions: Navigation chants, genealogies, and myths persisted alongside literacy.

-

Nuclear experience: Bikini and Enewetak exile produced laments, songs, and petitions to the UN, embedding global justice narratives.

-

Nationalism: Political movements in the 1960s pressed for independence, autonomy, or free association.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Food storage: Breadfruit pits, dried fish, and taro provided insurance.

-

Inter-atoll exchange: Canoe voyaging redistributed food in famine.

-

Colonial coping: Islanders balanced copra production with gardens.

-

Postwar dependence: Rations and aid substituted for lost autonomy; displaced Bikini islanders relied on imported foods.

Political & Military Shocks

-

Colonial succession: Spain → Germany → Japan → United States trusteeship.

-

World War II: Battles at Tarawa and Kwajalein left mass destruction.

-

Cold War: U.S. nuclear testing (1946–58) displaced islanders, sparking protests.

-

Decolonization: By the late 1960s, the Marshalls, Gilberts, and Carolines pressed for independence within or outside U.S. frameworks.

Transition

Between 1828 and 1971, East Micronesia transitioned from remote atoll societies to highly strategic Cold War outposts. Copra trade, missionization, and Japanese militarization had already altered lifeways, but U.S. nuclear testing and trusteeship uprooted entire communities. Despite environmental fragility and political subordination, Micronesians retained strong cultural traditions of navigation, kinship, and oral history while mobilizing for self-determination. By 1971, East Micronesia was poised to enter an independence era shadowed by both nuclear trauma and enduring resilience.