Micronesia (1252–1395 CE): Navigators, Shrines, and Atoll …

Years: 1252 - 1395

Micronesia (1252–1395 CE):

Navigators, Shrines, and Atoll Confederacies

Geographic and Environmental Framework

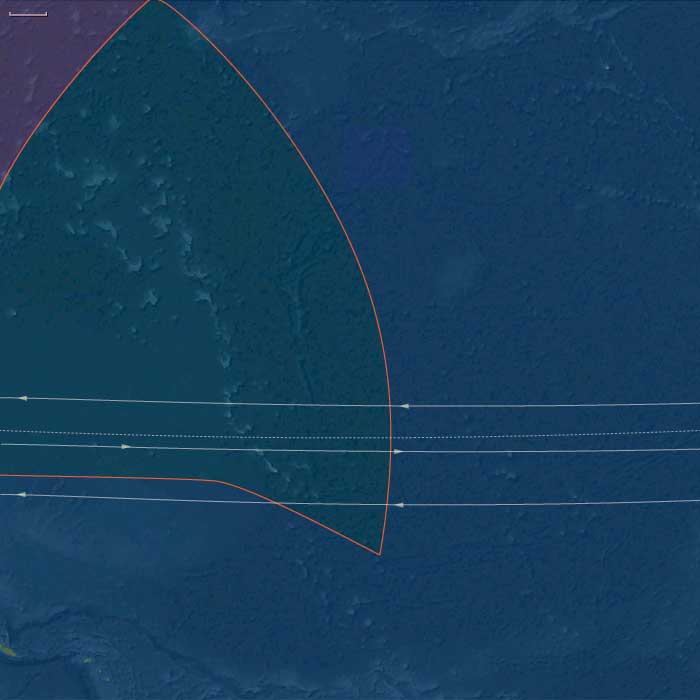

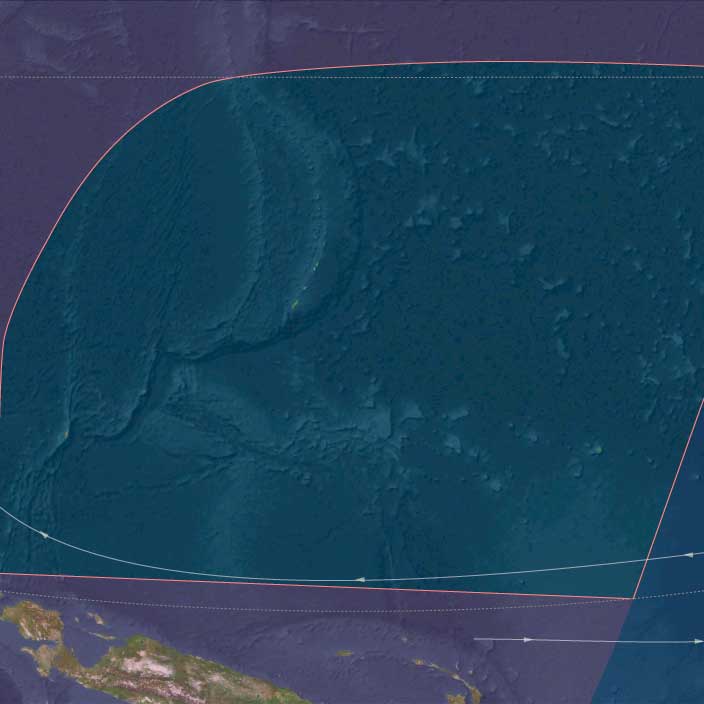

During the Lower Late Medieval Age, Micronesia stretched across the western and central Pacific, forming a vast constellation of coral atolls, volcanic high islands, and limestone plateaus.

It encompassed the Mariana Islands, Palau, and Yap in the west, extending through Kosrae, Nauru, Kiribati, and the Marshall Islands to the east—a maritime realm bound by ocean corridors, exchange alliances, and sacred navigation.

-

High islands such as Kosrae, Palau, and Yap offered fertile soils, freshwater streams, and reef-fringed lagoons suited to intensive horticulture.

-

Atolls of the Marshalls and Gilberts sustained communities on thin coral soils through arboriculture, taro-pit cultivation, and reef fishing.

-

Uplifted limestone islands, including Nauru and the northern Marianas, offered limited agriculture but abundant fisheries and nesting seabirds.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The gradual cooling of the Little Ice Age after c. 1300 CE brought greater rainfall variability, stronger typhoons, and intensified ENSO drought cycles.

-

High islands such as Yap, Palau, and Kosrae provided reliable rainfall, enabling irrigation and food storage.

-

Low atolls, vulnerable to drought and storm surge, relied on deep babai (swamp taro) pits breadfruit preservation, and inter-island aid.

-

These environmental contrasts fostered regional systems of tribute, reciprocity, and navigation, ensuring collective resilience.

Societies and Political Developments

Across Micronesia, communities organized around hereditary chiefs, ritual specialists, and federated systems of exchange that balanced autonomy and interdependence.

-

Kosrae: Centralized kingship (tokosra) reached its architectural zenith at Lelu, a coral-block city with causeways, canals, and walled compounds. Sacred rulers coordinated irrigation, tribute, and monumental labor, embodying divine order in stone.

-

Yap: Became the hub of the sawei system—a sphere of tribute linking hundreds of Caroline atolls. Outer islands sent offerings of breadfruit paste, mats, and shells to Yap in return for navigational training, protection, and prestige goods. Chiefs controlled rai (stone money) quarries, whose immense carved disks, transported from Palau, symbolized wealth and ancestral authority.

-

Palau: Clan-based chiefdoms built stone terraces and shrines, managed taro swamps, and developed rice cultivation—unique in Oceania. Large men’s houses (bai) served as political and ritual centers, their carved gables recounting creation myths and lineage history.

-

Mariana Islands: Village polities under matrilineal clans expanded latte-stone architecture, erecting megalithic pillars as foundations for chiefly dwellings and public halls. Warfare over land and reef tenure reflected growing population pressures.

-

Marshall Islands and Kiribati: Organized under hereditary iroij (paramount chiefs) and council elders meeting in the maneaba (assembly house). Their authority rested on inter-atoll cooperation and mastery of navigation.

-

Nauru: Maintained small clan communities combining gardens, coconut groves, and reef fishing, integrated into passing canoe circuits.

Economy and Exchange Networks

Micronesian economies combined tree-crop horticulture, taro irrigation, reef fishing, and reciprocal exchange that linked high islands and atolls into one of the most dynamic maritime systems of the Pacific.

-

Staples: coconut, breadfruit, pandanus, yam, and taro; babai cultivated in deep pits on atolls and irrigated terraces on high islands.

-

Fisheries: lagoon netting, fish weirs, turtle hunts, and pelagic trolling for tuna and bonito; breadfruit and fish paste preserved for dry seasons.

-

Trade circuits:

-

The sawei network radiated from Yap across the western Carolines, redistributing food, craft goods, and navigational lore.

-

Palau exported rai disks, fine mats, and carved ornaments; Kosrae sent timber, taro, and canoes in exchange for shells and cordage.

-

Marshalls and Gilberts sustained inter-atoll reciprocity, exchanging salt fish, mats, and fiber goods between drought-stricken and surplus islets.

-

Guam and the southern Marianas served as waystations for trade and ceremonial alliance.

-

Subsistence and Technology

-

Irrigation systems: engineered taro pondfields in Palau and Kosrae, with embankments, canals, and drainage controls.

-

Architecture: coral-block citadels at Lelu, bai houses in Palau, latte stones in the Marianas, and stone-money banks in Yap embodied political authority.

-

Navigation: outrigger canoes and crab-claw sails; navigators trained to read stars, ocean swells, and bird flight patterns—maintaining oral “stick charts” that mapped the sea through memory.

-

Craft industries: shell adzes, fiber nets, obsidian and coral tools, carved gables, and ritual masks combined utility with cosmological meaning.

Belief and Symbolism

Micronesian cosmology interwove ancestral veneration, navigation, and sacred geography:

-

Yap: Rai stones embodied the spirit of heroic voyages; each disk’s journey conferred sacred legitimacy.

-

Palau: Creation myths, clan totems, and ancestor shrines were carved into bai houses, merging art, ritual, and governance.

-

Kosrae: The stone city of Lelu mirrored the cosmic order, linking human hierarchy with divine kingship.

-

Marianas: Latte stones symbolized endurance and lineage, while rituals honored sea spirits and agricultural fertility.

-

Marshalls and Kiribati: Navigation was sacralized; voyagers invoked sea deities and star gods before departures.

Every voyage, crop, or monument reaffirmed the spiritual balance between land, ocean, and ancestry.

Adaptation and Resilience

Micronesians sustained complex strategies for survival under climatic uncertainty:

-

Diversified subsistence: blending arboriculture, fishing, and taro cultivation across ecological niches.

-

Reciprocity networks: the sawei system and inter-atoll gift exchanges redistributed surplus and stabilized communities after storms or droughts.

-

Monumental architecture: Latte, bai, and rai embodied social cohesion and ritual authority, reinforcing unity after environmental crises.

-

Navigation schools: safeguarded knowledge that linked scattered islands into a shared maritime world.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Micronesia had matured into an integrated oceanic system of tribute, navigation, and sacred monumentality:

-

Yap projected its influence through the sawei network, uniting hundreds of islands under cycles of exchange and ritual diplomacy.

-

Palau flourished as a center of carved artistry, irrigated taro, and early rice cultivation.

-

Kosrae stood as a volcanic stronghold of stone kingship, while the Marianas, Marshalls, and Gilberts perfected the governance of atolls through assemblies, voyaging, and preservation.

Together, these societies exemplified the balance of hierarchy and reciprocity, intellect and faith—an enduring maritime civilization that transformed the scattered isles of the western Pacific into a coherent world of stone, sail, and memory.