East Micronesia (820 – 963 CE): Atoll …

Years: 820 - 963

East Micronesia (820 – 963 CE): Atoll Adaptations, Kosraean Centralization, and Ocean-Wayfinding

Geographic and Environmental Context

East Micronesia includes Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, and Kosrae.

-

Kiribati (Gilbert Islands) and the Marshall Islands (two parallel chains, Ralik and Ratak) are mostly low coral atolls with thin soils, freshwater lenses, and extensive lagoons.

-

Nauru is an uplifted limestone island with limited arable pockets and rich nearshore fisheries.

-

Kosrae is a single high volcanic island with steep forested slopes, perennial streams, and a protective fringing reef—an ecological outlier that offered surpluses and political gravity.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Equatorial trade winds and a warm maritime regime prevailed.

-

ENSO variability produced periodic droughts that stressed atoll agriculture and water lenses, while typhoons occasionally damaged breadfruit groves and canoe fleets.

-

Kosrae’s orographic rainfall buffered shortages that hit the atolls harder.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Kiribati: kin-based lineages organized village life around the community meeting house (maneaba), with elders arbitrating land-use on narrow motu and rights to taro pits, groves, and reef sectors.

-

Marshall Islands: hierarchical but distributed authority—iroij (paramount chiefs), alab (lineage land stewards), and rijerbal (commoner workers)—managed land, labor, and lagoon tenure across Ralik–Ratak atolls.

-

Nauru: small, clan-centered communities balanced nearshore fishing, garden plots, and reef gleaning with exchange to passing canoes.

-

Kosrae: fertile valleys and secure water allowed the coalescence of sacred kingship (early forms of the tokosra), with centralized ritual leadership beginning to outscale atoll chiefdoms. The seeds of later Lelu court development were sown in this period, even if its monumental stone city would flourish later.

Economy and Trade

-

Atoll arboriculture: coconut, pandanus, and breadfruit formed staple canopies; swamp taro in excavated pits (babai) provided drought insurance.

-

Fishing & reef harvests: lagoon netting, trolling, weirs, and shellfish gathering produced steady protein; fermented breadfruit pastes and cured fish created cyclone/drought stores.

-

Inter-island exchange: preserved foods, fine mats, shell ornaments, high-quality cordage (sennit), and canoe parts circulated between atolls; Kosrae exported taro, breadfruit, timber, and craft goods in return for shells and specialized items from the low isles.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Water management: careful well-siting and grove mulching protected fragile freshwater lenses; taro pits were lined and composted to buffer salinity.

-

Canoe-building: outrigger sailing canoes (single and double) lashed with sennit; breadfruit and other hardwoods provided hulls on Kosrae, while atolls specialized in light, swift craft.

-

Navigation: wayfinding relied on star paths, swell patterns, seabird behavior, and (in the Marshalls) stick charts (rebbelib, meddo) mapping wave interference and island positions.

-

Food preservation: smoking/drying of fish and fermented breadfruit pastes stabilized calories across lean seasons.

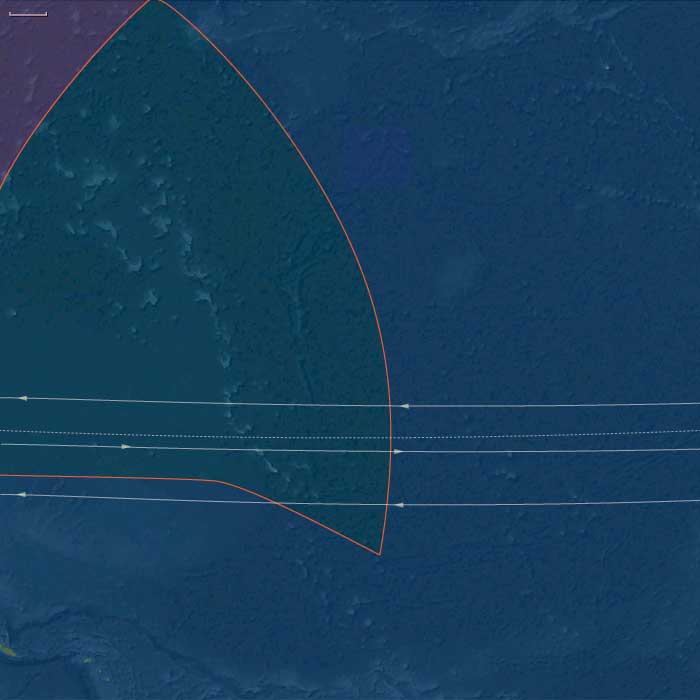

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Ralik–Ratak voyaging knit Marshall atolls into a shared political ecology; canoes moved seasonally with prevailing trades.

-

Gilbertian (Kiribati) circuits linked northern and southern atolls, coordinating marriage alliances and mutual-aid exchanges during drought.

-

Kosrae sat at the eastern Carolinian edge, drawing in visitors from neighboring high islands and dispatching surplus to surrounding low isles.

-

Nauru interacted opportunistically with passing Marshallese and Gilbertese vessels.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Sea and wind deities and ancestor spirits governed success in fishing, sailing, and grove fertility; ritual specialists mediated between community and ocean/weather powers.

-

In Kiribati, the maneaba embodied communal authority and sacred history; in the Marshalls, chiefly lines traced prestige to founding navigators and sacred lands.

-

Kosrae developed sacral kingship idioms—ritual first-fruits, temple feasts, and court specialists—that prefigured later urban ceremonial life.

-

Canoe consecrations and navigation chants embedded cosmology in everyday voyaging.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Risk-spreading portfolios—breadfruit, coconut, babai, reef fish, pelagic catches—reduced dependence on a single resource.

-

Preservation technologies (fermented breadfruit, dried fish) and storm-resistant arboriculture buffered shocks.

-

Mutual-aid pacts and inter-atoll voyaging redistributed food during droughts; Kosrae’s surpluses served as a regional safety valve.

-

Flexible land/reef tenure systems allowed households to rotate use, rest fragile patches, and share labor for pit excavation and canoe repair.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, East Micronesia had stabilized a resilient atoll–high island system:

-

Atolls in Kiribati and the Marshalls perfected water-lens gardening, reef tenure, and wayfinding, sustaining dense communities on scant soils.

-

Kosrae began to differentiate as a centralized sacred polity, a trend that would culminate in the Lelu stone court in later centuries.

-

Nauru occupied a modest but strategic niche, linking eastern and western atoll chains.

Together, these societies built a voyaging commons and subsistence toolkit that would carry East Micronesia through climatic swings and into a period of monumentalization and intensified exchange after 964 CE.