Melanesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): After …

Years: 909BCE - 819

Melanesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): After Lapita — Gardens, Ancestor Houses, and Canoe Worlds

Regional Overview

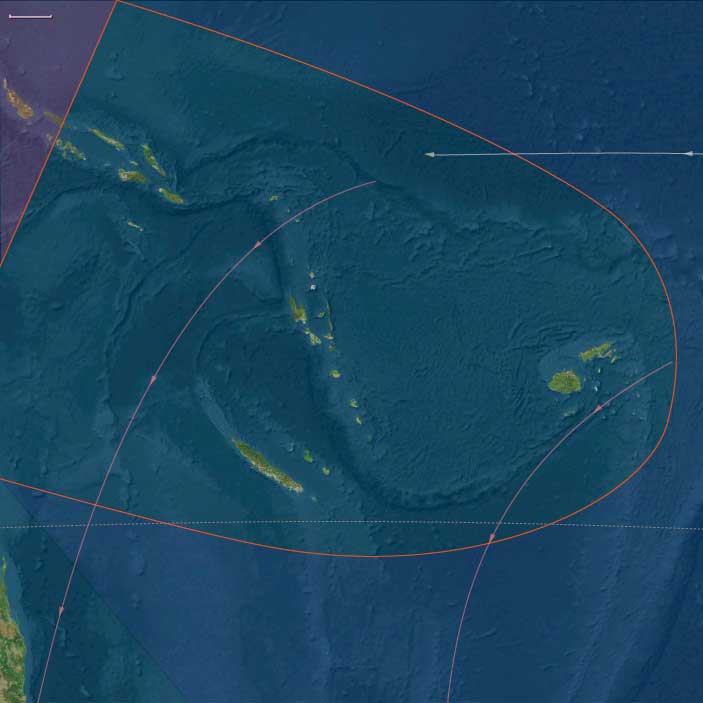

Across the green arc from New Guinea to Fiji, Melanesia entered the first millennium BCE as a region of transformation.

The expansive Lapita horizon, whose decorated pottery and seafaring reach had once united the southwest Pacific, was fragmenting into a constellation of localized cultures.

Yet in that very diversification lay Melanesia’s genius: each island and valley refined its own forms of horticulture, exchange, and ritual art, producing a world at once intensely regional and tightly networked.

By the end of this age, the societies of West Melanesia (New Guinea and the Bismarcks) and East Melanesia(Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, Solomons minus Bougainville) had each stabilized distinctive traditions that would, together, seed later Polynesian and Micronesian expansions.

Geography and Environment

Melanesia lies astride one of the planet’s richest convergence zones: volcanic ridges, coral-fringed coasts, and interior rainforests threaded with rivers.

Climatically, it oscillated between humid maritime stability and sporadic ENSO droughts. Fertile volcanic soils, high rainfall, and reef abundance supported dense populations and continuous adaptation.

The long chains of Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia provided stepping-stones for exchange; the high valleys of New Guinea offered terraced gardens and enduring refuge; the Bismarck Archipelago and Solomons bound them together through canoe routes and trade in obsidian, shells, and pigs.

Societies and Political Developments

West Melanesia: New Guinea and the Bismarcks

In the New Guinea Highlands, intensive agriculture—taro, yam, banana, and sugarcane—was already ancient. Drainage ditches and mound fields at Kuk and Wahgi Valley testify to continuous cultivation since deep prehistory.

By this era, kin-based “big-man” systems coordinated labor for feasts and exchange, converting surplus into political authority.

Along the coasts, the Sepik and Ramu river communities elaborated ceremonial men’s houses (haus tambaran), adorned with towering spirit boards and carved ancestor masks that embodied clan prestige.

Farther east, the Bismarck Archipelago and Manus became maritime hubs: their obsidian quarries (Talasea, Lou Island) supplied cutting-edge tools across the Pacific, while canoe-builders and shell-workers extended trade to the Solomons and beyond.

East Melanesia: Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, Solomons

In Vanuatu and Fiji, coastal and valley communities developed ranked societies anchored by grade rituals, where advancement required elaborate pig feasts and gift exchanges. Such ceremonies transmuted economic surplus into spiritual power and social order.

Villages multiplied along fertile deltas, while inland settlements farmed irrigated taro and yams.

In New Caledonia, early Kanak forebears cultivated yam gardens bounded by stone walls and celebrated first-fruit festivals that tied lineage to land.

Across the central Solomons, clan chiefdoms stabilized around ancestral shrines and canoe alliances that mediated rivalry and trade.

Economy and Exchange

Agriculture formed the base: taro, yam, banana, breadfruit, and coconut intercropped with pandanus and a range of root crops.

Pigs were universal symbols of wealth and ritual obligation. Arboriculture—careful management of tree crops—smoothed lean seasons.

Inter-island exchange moved prestige goods—shell rings, pig tusks, red feathers, basalt adzes, and fine mats—linking the high volcanic islands to the outer atolls.

The obsidian routes of the Bismarcks met the canoe lanes of Fiji–Vanuatu, binding Melanesia into a single economic sea.

This traffic, sustained by intricate kin alliances and ritual reciprocity, transformed geography into sociology: the ocean was not barrier but connective tissue.

Technology and Material Culture

Pottery traditions localized and gradually disappeared by the mid-first millennium CE, replaced by wood, fiber, and barkcloth media better suited to humid climates.

Stone and shell tools remained vital: adzes, chisels, and knives of shell or basalt enabled canoe construction and arboriculture.

The outrigger canoe reached high refinement—sleek hulls, crab-claw sails, sennit lashings—turning ocean channels into domestic space.

Ritual architecture—men’s houses in the west, grade-ceremony plazas in the east—embodied both artistry and cosmology, adorned with carvings, mats, and drums whose thunder echoed across valleys.

Belief and Symbolism

Melanesian religion centered on mana—the immanent force of ancestors and nature.

Ancestral spirits inhabited stones, trees, and carvings; ritual feasts repaid their gifts of fertility and peace.

Across both subregions, art was theology: shell ornaments, slit gongs, and pig tusks were not aesthetic luxuries but containers of power.

Myths of first voyages and ancestral emergence tied human origins to specific reefs and headlands, sacralizing geography.

In the highlands, initiation cycles reaffirmed alliance and exchange; in the islands, ceremonial grades transformed mortal status into ancestral continuity.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Melanesian societies mastered risk through diversification. Each community maintained complementary ecological zones: reef, garden, and forest.

In times of drought or cyclone, alliances mobilized food redistribution; exchange feasts converted social capital into material insurance.

In the Bismarcks and Solomons, redundancy among canoe routes allowed quick recovery from disruption; in highland valleys, multiple taro and yam varietals ensured food security.

Knowledge of wind, current, and season—encoded in myth and song—was as essential to survival as any tool.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 819 CE, Melanesia stood as a mature mosaic of agricultural, ceremonial, and maritime societies—a world of intricate gardens and greater canoes.

Its dual geography—West Melanesia’s mountain worlds and East Melanesia’s island chains—defined two complementary logics:

the first anchored in ancestral land and ritual architecture; the second outward-looking, oceanic, and exchange-driven.

Together they forged the Pacific’s connective core. From these shores would later flow both the navigators who reached Polynesia and the ritual forms that endured into the monumental age of the later centuries.

Thus Melanesia, more than any other region, illustrates how the great Pacific “world” divides naturally into coherent subregions — highland and island, garden and canoe, interior permanence and maritime reach — each sustaining the other across an ocean that was never empty, always alive.