Melanesia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene …

Years: 6093BCE - 4366BCE

Melanesia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Gardens of Exchange and the Obsidian Sea

Geographic & Environmental Context

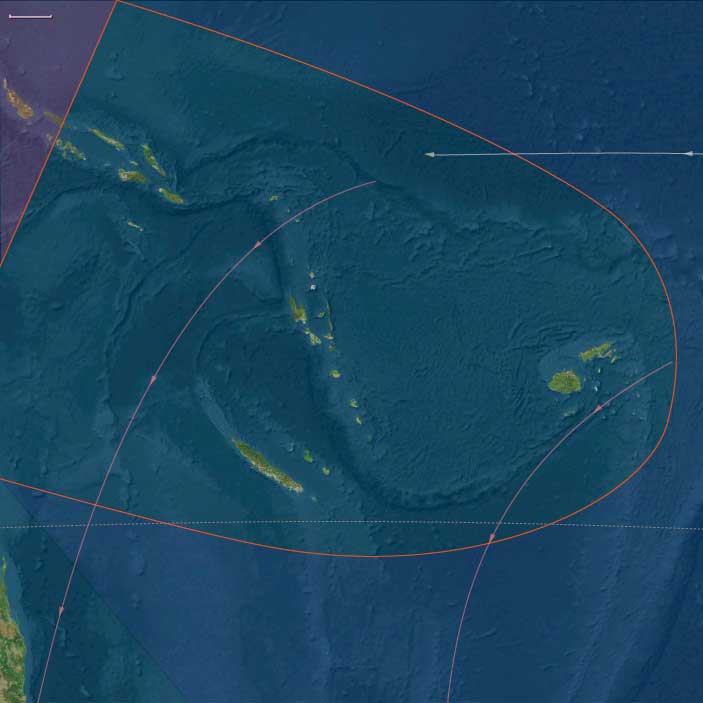

During the Middle Holocene, Melanesia formed a densely interconnected realm of volcanic mountains, coral-fringed coasts, and deep forest valleys, stretching from the highlands of New Guinea through the Bismarck Archipelago to the chains of the Solomons, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia.

By this time, sea levels had stabilized near their Holocene highstand, producing extensive estuarine lagoons and widening lowland plains. The landscape combined swamp-fed gardens, reef-bordered villages, and dense tropical forests punctuated by managed clearings.

The region’s geography was already an intricate ecological web: highland cultivation linked to coastal arboriculture, inland valleys to outer reefs, and volcanic uplands to fertile alluvia. These environments laid the foundation for one of the world’s oldest systems of sustained agroforestry and exchange.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm phase brought climatic stability with consistent rainfall and minimal cold-season variability.

High humidity and nutrient-rich volcanic soils favored dense vegetation growth and extended cropping cycles. Highland basins remained perennially wet, ideal for taro and banana cultivation, while lower coastal zones supported breadfruit, yam, and pandanus groves.

Occasional volcanic activity enriched soils, and periodic El Niño–type oscillations may have influenced rainfall but without long-term disruption. Overall, this was a warm, wet, and productive equilibrium that sustained continuous human occupation and innovation.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across Melanesia, societies developed highly organized horticultural systems blending agriculture, arboriculture, and foraging:

-

In the New Guinea highlands, ditch-fed taro and banana gardens spread across valley floors, evolving into the swamp-terrace agriculture seen at sites like Kuk.

-

Along the Papuan Gulf and northern coasts, pigs and chickens began to appear, complementing fishing, sago processing, and small-scale gardening.

-

In the Bismarck and Solomon Islands, village clusters with permanent house foundations and shell middens marked stable, long-term settlement.

-

Further east, in Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia, villagers maintained yam and taro plots interwoven with Canarium nut groves—an early form of agroforestry mosaic management.

Subsistence was diversified: reef fishing, nut gathering, and cultivated starches formed complementary systems. These were landscapes already under continuous human design—managed, productive, and resilient.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological sophistication kept pace with environmental abundance.

Ground-stone adzes, polished axes, and grinding slabs proliferated across the islands, supporting intensive wood- and canoe-working. Barkcloth (tapa) manufacture likely originated in this era, used for clothing and ritual.

The obsidian trade flourished: high-quality glass from New Britain’s Talasea sources, Manus, and the Banks and Santa Cruz Islands circulated through hundreds of kilometers of sea routes, forming one of the earliest long-distance exchange networks on Earth.

These systems foreshadowed the Lapita horizon, in which pottery, obsidian, and navigation would unite Melanesia into a single cultural sphere.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Middle Holocene witnessed the full emergence of maritime Melanesia.

Canoe technologies evolved—outrigger stability systems and improved lashings—enabling confident inter-island travel.

Regular trade circuits connected:

-

The Bismarcks and Bougainville, hubs of obsidian distribution and pig exchange.

-

The Solomons, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia, linked by networks that shared nut crops, shell ornaments, and ritual goods.

-

Highlands and coasts, joined by river valleys and mountain passes through which stone tools, salt, and forest produce moved.

These routes integrated Melanesia into a single economic continuum—a web of seaways and pathways that transformed geography into community.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Ritual life reflected both ancestral veneration and social cooperation.

Burial practices often placed the dead beneath house floors or within village precincts, emphasizing continuity between household and lineage.

Feasting traditions—centered on yam harvests, pig slaughter, and nut collection—strengthened alliances and redistributed surplus.

Early rock art in the Bismarck and Solomon Islands depicted cultivation, canoes, and ritual figures, while shell jewelry and decorated adzes served as prestige symbols within exchange systems.

These expressive forms reveal societies where ritual and subsistence were inseparable—each feast, voyage, and garden plot an act of renewal.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Melanesian communities engineered ecological stability through diversity and reciprocity.

-

Highland ditch systems controlled flooding and maintained soil fertility.

-

Coastal arboriculture buffered against cyclone damage.

-

Multi-island alliances provided insurance against local reef or crop failure, exchanging surplus across ecological zones.

This distributed risk strategy—horticulture + arboriculture + exchange—created one of the most resilient systems in the prehistoric world, balancing sustainability with innovation.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Melanesia stood as a mature horticultural–exchange civilization in everything but name.

Its communities had mastered the interplay of earth and ocean, turning volcanic instability and archipelagic fragmentation into engines of cultural coherence.

Obsidian routes stitched the region together, and managed landscapes—swamps, gardens, nut groves, and reef fisheries—functioned as enduring ecological and social systems.

The stage was set for the Lapita expansion and the later spread of Austronesian languages, technologies, and voyaging traditions.

This was the epoch when Melanesia became the living heart of the western Pacific, where gardens, ancestors, and canoes together defined the human mastery of the tropical sea.