Melanesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Melanesia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Sahulian Highlands, Volcanic Arcs, and the Unpeopled Frontiers of Remote Oceania

Geographic & Environmental Context

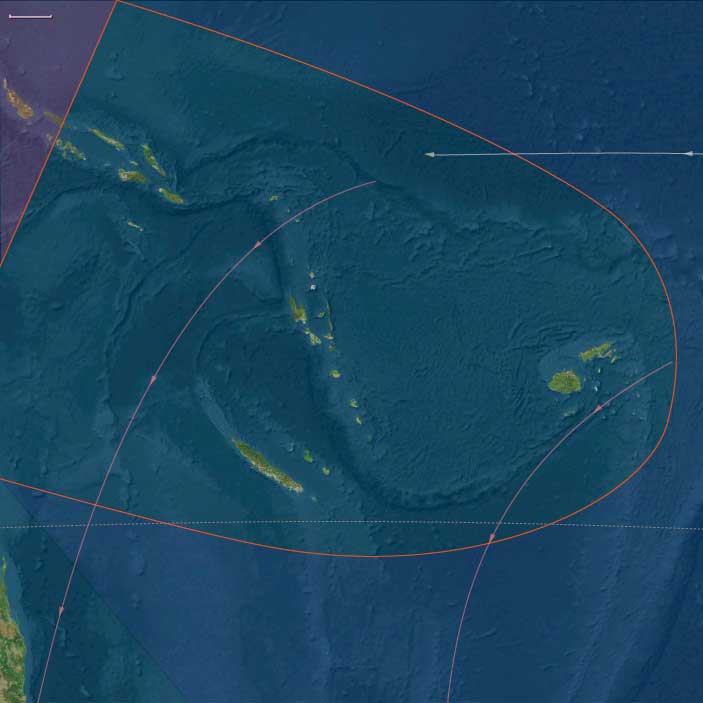

During the height of the Late Pleistocene glaciation, Melanesia was divided into two very different worlds:

-

The western realm, including New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and the northern Solomons (Bougainville–Buka)—all part of the larger Sahul continent joined to Australia by the exposed Torres Shelf.

-

The eastern realm, the isolated island chains of Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the central–eastern Solomons (Guadalcanal–Malaita–Makira–Santa Cruz)—the volcanic and coral highlands of Remote Oceania, still uninhabited by humans.

Sea level lay roughly 100 meters below present, exposing broad continental shelves in the west and narrowing reef lagoons in the east. The Sahulian landmass extended north into Arafura–Carpentaria plains, while New Guinea’s central ranges rose into glaciated heights with periglacial basins and frost-prone valleys.

To the east, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia stood as isolated volcanic arcs emerging steeply from deep basins—ecologically rich but geographically inaccessible to the foragers of the western coasts.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Glacial World (49–30 ka):

Mean sea-surface temperatures across the Southwest Pacific were 2–3 °C cooler. Trade winds strengthened, intensifying upwelling on leeward coasts and bringing drier conditions to New Guinea’s highlands and valleys. The Central Cordillera supported small alpine glaciers, and montane forests gave way to open grassland and subalpine scrub. -

Toward the LGM (~30–28 ka):

Aridity peaked; coastal mangroves retreated; many lowland rivers cut deeply into exposed continental shelves. Cyclones and volcanic activity persisted episodically across the arc from New Britain to Fiji. -

Regional Contrast:

Western Melanesia retained significant rainfall and river flow, while Remote Oceania remained wetter overall but climatically cooler and more seasonally variable.

Western Melanesia: The Sahulian Heart

By this epoch, modern humans had long been established in New Guinea and the Bismarcks, forming one of the world’s most enduring highland–lowland adaptations.

-

Subsistence & Settlement

Foragers occupied glacial uplands such as the Ivane Valley (Central Highlands) and Kafiavana, where hearths, stone flakes, and grindstones attest to cold-climate resource management—small-game hunting, nut and tuber gathering, and controlled fire use to maintain open ground.

Along the Sepik–Ramu and Papuan Gulf, coastal and riverine communities exploited fish, mollusks, and estuarine mammals; reef flats now stranded high and dry would later become mangrove forests.

Fire regimes reshaped highland grasslands, encouraging regrowth and visibility for marsupial hunts, while wild tubers (precursors of yam and taro) were deliberately managed in cleared patches—the world’s earliest evidence of proto-horticultural systems. -

Technology & Material Culture

Flaked quartz and chert tools dominated; ground-stone axes began to appear for woodworking. Plant-fiber nets and string bags, now perishable, were probably in common use. Ochre and hematite were employed for body painting and symbolic burials.

Shelters—rock overhangs and built windbreaks—were adapted to frost and seasonal cold. -

Movement & Interaction Corridors

River corridors (Strickland, Fly, Sepik, Ramu) served as travel and exchange routes, connecting inland valleys with coastal lowlands. Although full ocean crossings were still rare, obsidian from New Britain occasionally reached New Guinea sites, hinting at incipient seafaring competence along sheltered coasts and straits. -

Cultural & Symbolic Life

Pigment use and ritualized burials reveal social continuity and symbolic depth. Fire—both a practical and ceremonial tool—was central to highland identity and landscape management.

Eastern Melanesia: The Unpeopled Frontier

Beyond the Sahul shelf lay Remote Oceania, a vast Pacific expanse scattered with volcanic arcs and coral plateaus—Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the eastern Solomons—all still empty of human life.

-

Ecosystems and Biota

Dense rainforests and cloud forests cloaked the high islands, nourished by volcanic soils. Reef and lagoon systems were narrower at glacial lowstand but maintained robust coral and fish populations. Seabird colonies, turtles, and flying foxes dominated terrestrial fauna; large reptiles and endemic birds filled ecological niches undisturbed by mammalian predators. -

Environmental Stability

Despite cooler sea-surface temperatures, reef–lagoon productivity remained high, buffering ecosystems through climatic oscillations. Volcanic ash periodically enriched soils, supporting evergreen canopies. These landscapes matured in isolation—an ecological Eden awaiting human discovery.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Across the entire Melanesian domain, resilience stemmed from diversity and isolation:

-

In Western Melanesia, flexible foraging and fire-based ecosystem management allowed human populations to thrive through glacial extremes.

-

In Eastern Melanesia, biological systems maintained equilibrium without human influence—reefs recovered, forests recycled, and volcanoes renewed soils on cyclical timescales.

The contrast between peopled west and empty east defined Melanesia’s enduring duality: one a cradle of continuous habitation and innovation, the other a pristine wilderness preserved by distance.

Transition Toward the Holocene

By 28,578 BCE, Western Melanesian foragers had mastered every ecological zone from alpine valleys to coral flats, forming the cultural base of the later Papuan–Austronesian continuum.

To the east, volcanic and coral islands awaited the rise of sea levels and the eventual emergence of long-range voyagers.

The post-glacial world would soon redraw coastlines, creating new estuaries, lagoons, and archipelagos—the stage on which Lapita seafarers would one day appear.

But for now, Melanesia remained a divided world: the oldest continuously inhabited mountains on Earth facing a still-unpeopled Pacific horizon.