Melanesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

Melanesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Forests, Gardens, and the First Sea Roads

Geographic & Environmental Context

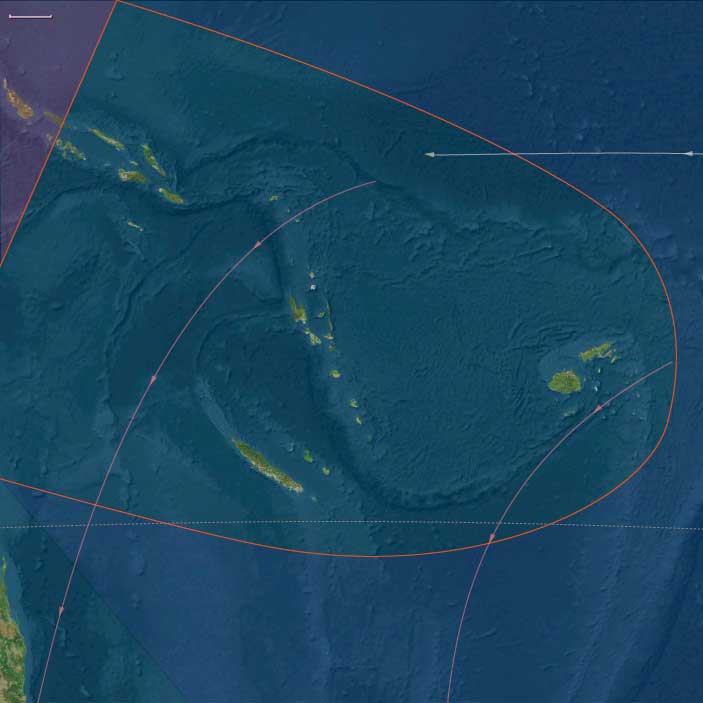

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Melanesia—stretching from New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago to the Solomon chain, Vanuatu, Fiji, and New Caledonia—underwent a profound ecological and cultural transformation.

At the Last Glacial Maximum, lowered seas fused many islands into larger landmasses. As the ice melted, rising waters fragmented coastal plains, creating the modern archipelagos and isolating highland basins.

-

West Melanesia (New Guinea, Bismarcks, Bougainville): vast valleys, expanding rainforests, and active volcanoes framed by rich reefs and mangrove deltas.

-

East Melanesia (Solomons, Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia): newly separated island chains with widening lagoons and thriving coral platforms.

By 7,800 BCE, the great Sahul–Melanesian bridge had vanished beneath the sea, leaving New Guinea and its eastern satellites distinct but still visible across narrow straits—a geography that would nurture the Pacific’s first sustained voyaging traditions.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The end of the Pleistocene brought warmer, wetter climates and the full onset of the Holocene monsoon regime:

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): sharp warming, heavier rainfall, and glacier retreat in the New Guinea highlands; forest expansion in valleys and along coasts.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): brief cooling and drying; temporary contraction of montane forests.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): sustained warmth and humidity; stable rainfall re-established dense lowland and montane forests; coral reefs reached modern vigor.

These oscillations alternately exposed and drowned plains, prompting both adaptation in agriculture and the emergence of maritime corridors.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across Melanesia, lifeways diversified as people adjusted to deglaciation and expanding tropical biomes:

-

Highlands of New Guinea:

The Kuk Swamp system began forming precursors to drainage channels by c. 10,000–9,000 BCE. Here, people managed taro, banana, yam, and sugarcane, creating the world’s earliest known horticultural landscapes. Seasonal settlements along valley margins indicate growing sedentarism. -

Lowlands and coasts (New Guinea & Bismarcks):

Forager–fisher–gardeners exploited shellfish, reef fish, and forest nuts (Canarium, pandanus). Mangroves and estuaries offered stable protein year-round. Arboriculture (tree crop tending) and periodic burning expanded mosaic habitats. -

Island arcs (Solomons to Fiji & New Caledonia):

Communities established semi-sedentary coastal hamlets near lagoons and estuaries, supported by broad-spectrum diets—reef fish, shellfish, bird and reptile meat, and wild roots/tubers. Evidence of nut groves and forest-edge management points to early landscape control.

Population densities remained modest, but communities were increasingly anchored to specific territories defined by reef passes, valleys, and resource-rich bays.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological innovation mirrored this dual terrestrial–marine focus:

-

Ground-stone axes and adzes emerged for forest clearance and woodworking; flaked tools persisted for finer work.

-

Obsidian from the Bismarck volcanic chain (Talasea, Lou) circulated widely—marking one of the earliest systematic exchange networks in human history.

-

Cordage, baskets, and bark containers supported mobility and food storage; shell ornaments and ochre burials continued symbolic traditions.

-

Early canoe forms—likely hollowed logs stabilized with outriggers—enabled short open-sea crossings between visible islands, laying foundations for Oceanic seafaring.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Melanesia’s fragmented geography became an engine of connection rather than isolation:

-

West Melanesia: regular crossings linked New Guinea ⇄ Bismarcks ⇄ Bougainville, distributing obsidian, shell, and forest products.

-

East Melanesia: expanding inter-island voyaging joined Solomons ⇄ Vanuatu ⇄ Fiji ⇄ New Caledonia, forming a maritime network that prefigured later Remote Oceania circuits.

-

Highland–lowland exchange systems traded salt, stone, and forest goods for marine shells and pigments.

This dynamic flow of goods and knowledge marked the first sustained inter-island navigation in the Pacific realm.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Cultural expression blossomed with environmental security:

-

Rock art traditions flourished in New Guinea valleys and island caves—depicting fauna, geometric patterns, and spirit figures linked to fertility and ancestry.

-

Ochre use in burials, shell jewelry, and carved bone objects reflected ritual continuity.

-

The integration of forest and sea cosmologies—mountain spirits, ancestor shells, water serpents—rooted identity in ecological abundance and exchange.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience derived from diversified subsistence and land–sea integration:

-

Horticulture and arboriculture stabilized food supplies amid shifting rainfall and rising seas.

-

Reef harvesting and lagoon fisheries ensured high protein availability even in climatic downturns.

-

Voyaging alliances between neighboring islands offset local resource failures and cemented social ties.

-

Forest regrowth management through selective clearing and fire maintained balance between cultivation and wild biodiversity.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Melanesia stood as one of humanity’s most sophisticated forager–horticultural regions:

-

In West Melanesia, the New Guinea highlands had pioneered swamp cultivation and forest management—among the world’s earliest farming systems.

-

In East Melanesia, inter-island voyaging and lagoon-based economies anticipated the maritime adaptations of later Lapita and Polynesian cultures.

Together, they defined a dual legacy—gardens of earth and gardens of sea—rooted in innovation, mobility, and ecological reciprocity that would shape Pacific civilization for the next ten millennia.