Melanesia (1108 – 1251 CE): Island Chiefdoms …

Years: 1108 - 1251

Melanesia (1108 – 1251 CE): Island Chiefdoms and Maritime Frontiers

Between 1108 and 1251 CE, the islands of Melanesia flourished within a stable, warm, and fertile Pacific world. From the terraced valleys of New Guinea to the coral lagoons of Fiji, societies balanced horticulture, fishing, and exchange across a mosaic of cultures. This age, marked by the Medieval Warm Period’s steady climate, fostered dense populations, complex ritual orders, and vigorous inter-island trade. Melanesia stood as the vital middle ocean between the highlands of New Guinea and the emerging chiefdoms of Polynesia—a world of cultivated gardens, navigated seas, and sacred exchanges.

Geographic and Environmental Context

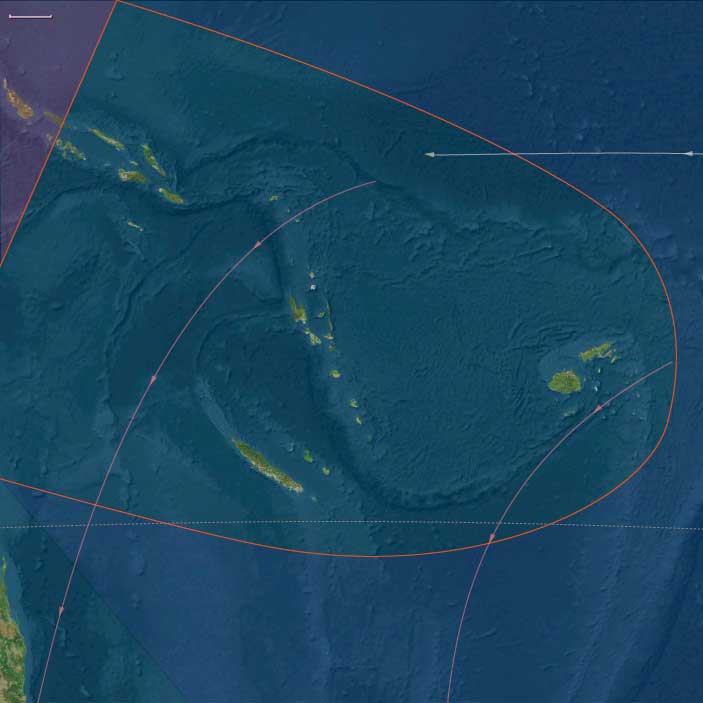

Melanesia extended from the high mountain ranges of New Guinea through the Bismarck Archipelago, Bougainville, and the Solomon Islands, to Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and Fiji.

This vast archipelagic region encompassed every environment of the tropical Pacific—fertile highlands, forested slopes, river deltas, volcanic islands, and reef-fringed lagoons.

-

New Guinea’s highlands supported intensive agriculture in enclosed valleys.

-

The Solomon chain and Vanuatu offered fertile coasts and interior forests.

-

Fiji, positioned between Melanesia and Polynesia, acted as both cultural bridge and maritime hub.

The combination of mountain and sea fostered intricate systems of exchange, where each island’s ecological distinctiveness became a foundation for interdependence.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period provided long intervals of consistent rainfall and moderate warmth.

Highland gardens flourished; coastal fisheries remained abundant.

Cyclones periodically struck the low islands, but geographic dispersion and adaptive exchange minimized impact.

El Niño–driven droughts occasionally challenged subsistence in New Guinea and the Solomons, prompting diversification of crops and storage practices.

Overall, the period’s stability allowed agricultural intensification and demographic growth across the region.

Societies and Political Developments

By this age, Melanesia was a landscape of chiefdoms, ritual confederacies, and emerging coastal hierarchies.

-

In New Guinea, highland communities expanded in number and density, governed by big-man systems in which prestige arose from generosity, feasting, and ritual authority rather than hereditary rule.

-

On the coasts and offshore islands, stratified chiefly systems developed, with hereditary leaders controlling trade and sacred knowledge.

-

Bougainville and the northern Solomons formed connective frontiers, blending Melanesian and Polynesian institutions through marriage and exchange.

-

In Vanuatu, decentralized kin groups emphasized clan governance but acknowledged powerful ritual leaders.

-

Fiji moved toward more formalized hierarchies, building fortified villages and developing proto-chiefly networks that foreshadowed later state-like polities.

-

New Caledonia retained distinct, lineage-based structures emphasizing land rights and collective ritual.

These systems varied in scale but shared a unifying principle: authority flowed from the management of land, exchange, and spiritual power.

Economy and Trade

Agricultural diversity anchored Melanesian prosperity.

Highlands and larger islands cultivated yams, taro, bananas, and sugarcane, supplemented by sweet potato and breadfruit on lower islands.

Pig husbandry underpinned both diet and ceremonial exchange, while fishing and reef harvesting supplied abundant protein.

Trade networks bound this economy together:

-

Highland–coastal exchange carried pigs, shells, and stone tools along mountain trails.

-

Maritime trade linked island chains through canoes, circulating pottery, mats, tapa cloth, obsidian, pearl shell, and ritual valuables.

-

Fiji’s position made it the pivot between Melanesia and Polynesia; Tongan and Samoan voyagers imported textiles and ceremonial goods while exporting timber, canoes, and mats.

Wealth was measured not in accumulation but in circulation—in feasts, marriages, and gifts that transformed material abundance into spiritual power.

Subsistence and Technology

Technological systems reflected both continuity and refinement.

-

Agriculture: Swidden gardens, irrigated taro terraces, and terraced slopes in New Guinea and Fiji supported dense populations.

-

Animal husbandry: Pigs were the universal wealth animal, feeding ritual economies and defining social rank.

-

Tools: Stone and shell adzes, digging sticks, and bone ornaments remained essential implements.

-

Architecture: Ceremonial houses—elaborate in New Guinea, monumental in the Solomons and Vanuatu—served as centers of clan identity.

-

Canoes: Outrigger and double-hulled vessels connected every coastal society, enabling not just trade but cultural integration across seas that were highways rather than barriers.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Melanesia’s geography demanded mobility.

-

In the New Guinea highlands, trails linked valleys through exchanges of pigs, shells, and ritual objects.

-

Coastal voyages followed the Huon Gulf and Bismarck archipelago, moving obsidian, pottery, and mythic narratives.

-

Bougainville and the Solomons exchanged ceremonial goods that joined Melanesia to the Polynesian sphere.

-

Fiji and Tonga lay at the crossroads of Pacific voyaging; sailors, traders, and priests moved freely between these regions, spreading crops, technologies, and genealogies.

This fluidity of movement sustained what might be called a Pan-Melanesian world, an interconnected domain of agriculture, exchange, and ritual knowledge.

Belief and Symbolism

Spiritual life permeated every action.

Ancestor veneration formed the core of belief: the dead were ever-present, guiding fertility, weather, and social harmony.

Mana, or spiritual potency, flowed through chiefs, sacred stones, and ritual exchanges.

Ceremonial feasts, pig offerings, and dances reaffirmed the bond between living communities and their ancestral guardians.

Ritual houses displayed carvings and masks depicting mythic beings—figures of creation, fertility, and warfare.

In Fiji and parts of the Solomons, the merging of Melanesian and Polynesian cosmologies introduced new deities and ceremonial complexity, blending sea and land traditions.

Religion was not separate from governance; it was its essence—authority expressed through the stewardship of sacred relations between people and nature.

Adaptation and Resilience

Melanesian societies demonstrated profound resilience.

Agricultural diversity cushioned against cyclones and drought; inter-island exchange provided redundancy; ritual and kinship bound communities in mutual support.

When environmental shocks occurred, leadership—whether of chiefs or big-men—was measured by the ability to redistribute food and renew ritual order.

The fusion of land, lineage, and spirituality produced adaptive systems capable of absorbing stress without collapse.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251 CE, Melanesia was a dynamic and cohesive world of island chiefdoms and highland confederacies.

-

In the New Guinea highlands, populous agricultural societies and complex ceremonial systems defined inland life.

-

Along the coasts and islands, hierarchical polities integrated Melanesian and Austronesian traditions.

-

Fiji and neighboring archipelagos acted as bridges between Melanesia and Polynesia, sharing crops, myths, and navigational skills that would shape the Pacific for centuries.

With its mosaic of horticulture, voyaging, and ritual exchange, Melanesia stood as a living continuum between the ancient agricultural heartlands of New Guinea and the expansive maritime civilizations of Polynesia—a testament to the Pacific’s enduring ingenuity and ecological intelligence.