Northeastern Eurasia (1828–1971 CE) From Tsarist …

Years: 1828 - 1971

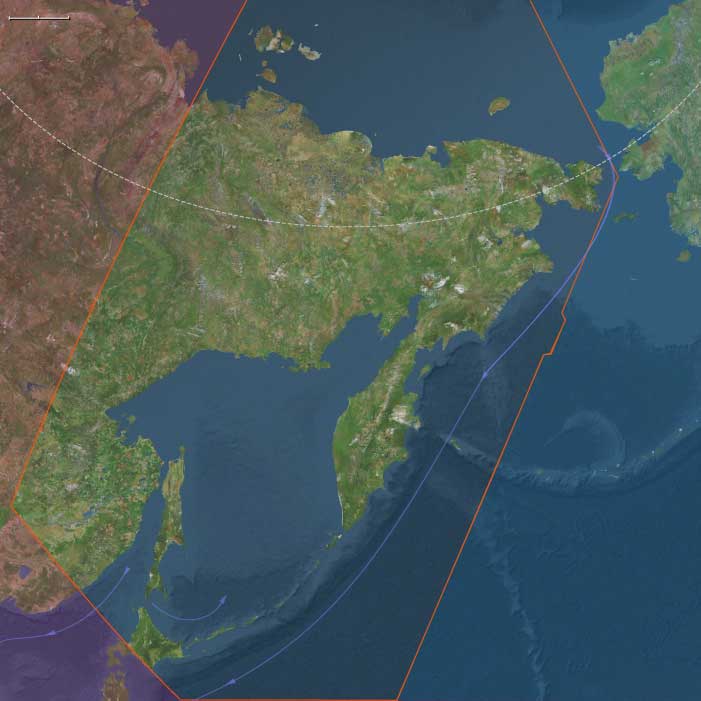

Northeastern Eurasia (1828–1971 CE)

From Tsarist Frontiers to Soviet Heartlands and Cold War Rimlands

Geography & Environmental Context

Northeastern Eurasia consists of three fixed subregions:

-

Northeast Asia — eastern Siberia (including Primorsky Krai), Sakhalin, the Chukchi Peninsula, Wrangel Island, Kuril Islands, and Hokkaidō (except its extreme southwest).

-

Northwest Asia — western and central Siberia from the Urals to roughly 130°E, including the West Siberian Plain, Altai, and the Central Siberian Plateau.

-

East Europe — the European portion of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, together with the Russian republics west of the Urals.

Anchors include the Arctic Ocean littoral (Kara, Laptev, and Okhotsk seas), the great river systems of the Ob–Irtysh, Yenisei, Lena, Amur–Ussuri, Dnieper, Don, and Volga, and the industrial–urban nodes of Leningrad (St. Petersburg), Moscow, Kyiv, Novosibirsk, Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, Vladivostok, and Sapporo. From tundra and taiga to loess plains and monsoon coasts, the region spans half the Northern Hemisphere’s climates and biomes.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

A sharply continental regime dominated interiors: long, frigid winters and short summers. The tail of the Little Ice Age persisted into the 19th century, then gave way to gradual warming, earlier river thaws, and glacier retreat in the Altai and Kamchatka by the mid-20th century. Periodic dzud winters devastated herds; drought pulses struck the Ukrainian steppe and Lower Volga (famines in the 1890s and early 1920s, and the Holodomor, 1932–33). In the Far East, typhoons and sea-ice shifts shaped fisheries; permafrost constrained construction across Siberia.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Indigenous lifeways: Evenki, Nenets, Khanty, Chukchi, Koryak, Nivkh, Yupik, and Ainu sustained reindeer herding, sea-mammal hunting, fishing, trapping, and foraging—progressively curtailed by colonization, collectivization, and settlement policies.

-

Tsarist and Soviet expansion: Villages and penal settlements pushed east along the Trans-Siberian and river corridors; after 1917, collectivized agriculture and kolkhoz/sovkhoz systems reorganized the countryside of East Europe and southern Siberia.

-

Urbanization and industry: European Russia’s cities ( Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Donbas ) became heavy-industry cores; Siberia’s hubs ( Novosibirsk, Kemerovo, Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk ) rose on coal, metals, and hydro, while Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, and Sapporo anchored the Pacific rim.

Technology & Material Culture

Railways (Trans-Siberian, 1891–1916; later Turk-Sib, branch lines) integrated steppe, taiga, and ports. Hydropower (e.g., Krasnoyarsk and Bratsk dams) and mining complexes transformed landscapes. In East Europe, steel, machine-building, and chemicals defined mass industrialization; in Northeast Asia, shipyards, ports, and fisheries expanded, while Hokkaidō underwent Meiji-to-postwar colonization and industrial growth. Everyday material culture shifted from log izbas and yurts to khrushchyovka apartments; radios, then TVs, entered homes by the 1960s.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

River highways: Seasonal shipping on the Ob, Yenisei, Lena, and Amur pre-dated and then fed rail hubs.

-

Trans-continental rails: Funneled grain, coal, ore, and people between European Russia and the Pacific; wartime evacuations (1941–42) relocated factories east.

-

Maritime arcs: The Okhotsk and Japan seas, Sakhalin–Hokkaidō–Kurils chain, and the Northern Sea Route(seasonal) tied fisheries, timber, and defense installations into Pacific networks.

-

Forced mobility: Tsarist exile and the Soviet Gulag (Kolyma, Norilsk, Vorkuta) drove coerced resettlement and resource extraction at massive human cost.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Orthodox Christianity, Islam (in the Volga–Ural and North Caucasus margins of East Europe), Buddhism (Buryat and Mongol spheres), shamanic traditions, and—on Hokkaidō—suppressed Ainu culture framed identity against the rise of secular ideologies. Russian literature, music, and film radiated from Moscow and Leningrad; Soviet monumentalism and avant-gardes coexisted uneasily. Indigenous carving, song, and festival cycles persisted in Siberia and the Arctic, often underground, reviving visibly in the later 20th century.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Permafrost engineering (pile foundations, winter roads) and taiga architecture enabled Siberian settlement.

-

Pastoral strategies: Herd diversification and seasonal migrations buffered dzud risk; state reindeer farms mixed traditional practice with planned quotas.

-

Agrarian adaptations: Shelterbelts, canals, and later the Virgin Lands campaigns extended cereal belts—often with soil erosion and dust storms by the 1960s.

-

Conservation beginnings: Zapovednik nature reserves (from 1916) protected representative biomes, even as industrial pollution rose in the Donbas, Upper Volga, and Kuzbass.

Political & Military Shocks

-

Tsarist consolidation and reform: The Emancipation of the Serfs (1861); Siberian penal colonization; the founding of Vladivostok (1860); Sakhalin as penal colony.

-

Revolution and Civil War (1917–22): Collapse of empire; shifting fronts across East Europe; creation of the USSR (1922).

-

Collectivization and terror: The Holodomor (1932–33) in Ukraine; purges; mass deportations to the Gulag and internal exiles in Siberia and the Far North.

-

Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) and Sakhalin/Kurils disputes; Hokkaidō settler colonialism and Ainu dispossession.

-

World War II: The Eastern Front ( Moscow, Stalingrad, Kursk, Leningrad ); devastation and liberation; Soviet seizure of southern Sakhalin and the Kurils (1945).

-

Cold War: East Europe as Soviet core; Northeast Asia militarized on both sides—the Pacific Fleet at Vladivostok; closed cities; the DEW Line/radar arcs in the Arctic; border incidents along the Amur by the late 1960s.

Transition

Between 1828 and 1971, Northeastern Eurasia was remade from a mosaic of imperial frontiers and Indigenous homelands into the industrial heartlands and strategic rimlands of two modern states: the USSR and Japan. Railways, mines, and dams bound taiga and tundra to Moscow; Hokkaidō’s Meiji-to-postwar transformation integrated it into Japan’s national economy. The costs were immense—famines, repression, deportations, cultural suppression—yet the region also generated vast material output and scientific achievement. By 1971, Northeastern Eurasia stood as a Cold War fulcrum: East Europe anchoring Soviet power, Northwest Asia supplying raw materials and hydro-electricity, and Northeast Asia bristling with fleets, airbases, and fisheries—its peoples negotiating survival and renewal between permafrost, ports, and power blocs.

People

- Alexander Dubček

- Anton Chekhov

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky

- Joseph Stalin

- Leo Tolstoy

- Nikita Khrushchev

- Yuri Gagarin

Groups

- Russian Orthodox Church

- Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), or Soviet Union

- Czechoslovakia (restored)

- Warsaw Pact (Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Assistance)

Topics

- November Uprising, Cadet Revolution, or Polish Rebellion of 1830-31

- 1848, Revolutions of

- Crimean War

- Emancipation reform of 1861

- Russo-Turkish War (1877-78)

- World War, First (World War I)

- October (November) Revolution, Russian

- Bolshevik Revolution

- World War, Second (World War II)

- Cold War

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Prague Spring

Commodoties

Subjects

- Commerce

- Writing

- Conflict

- Faith

- Government

- Scholarship

- Custom and Law

- Technology

- Metallurgy

- Aeronautics