The Funan state exercises control over the …

Years: 388 - 531

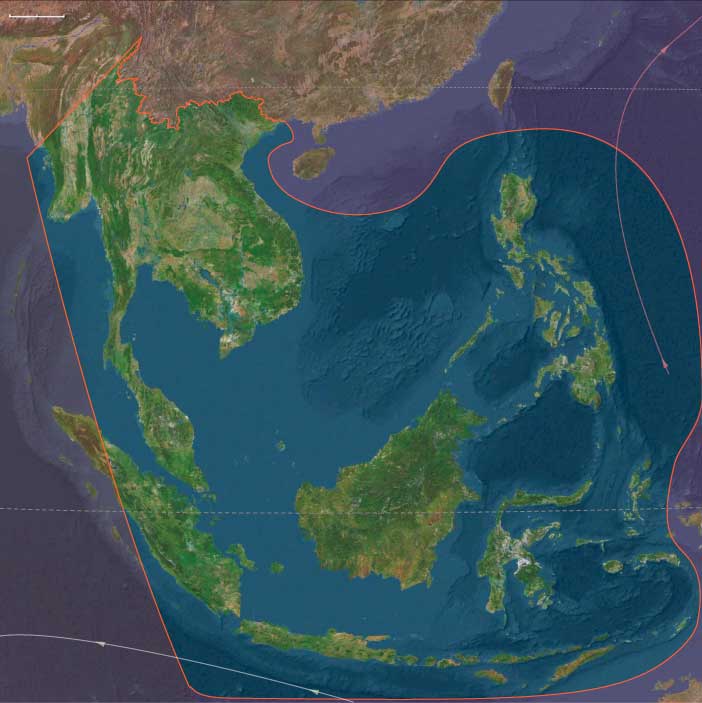

The Funan state exercises control over the lower Mekong River area and the lands around the Tonle Sap by the fifth century CE.

It also commands tribute from smaller states in the area now comprising northern Cambodia, southern Laos, southern Thailand, and the northern portion of the Malay Peninsula.

Locations

Groups

Topics

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 29 total

Mediterranean Southwest Europe (388–531 CE): Imperial Decline, Barbarian Ascendancy, and Cultural Transformation

The age 388–531 CE in Mediterranean Southwest Europe encompasses profound shifts, including the final decline of Western Roman imperial authority, the rise of Germanic kingdoms, and significant religious and cultural transformations. These events deeply influence the historical trajectory of the region, laying the foundations of medieval Europe.

Division and Decline of the Roman Empire (388–411 CE)

In 395 CE, the Roman Empire definitively splits into Western and Eastern halves, marking a turning point. The Western Empire, weakened by internal strife and external invasions, progressively dissolves. Emperor Honorius (r. 395–423 CE) struggles against invasions, commissioning his sister, Galla Placidia, and her husband, the Visigothic king Ataulf, to stabilize Iberia. Their efforts partially restore order, with the Visigoths settling permanently in Spain, subduing the Suevi, and pushing the Vandals into North Africa.

Visigothic Kingdom and Ecclesiastical Authority (412–447 CE)

The Visigoths, highly Romanized, establish their capital at Toledo by 484 CE, governing in the emperor's name as imperial patricians. Despite their relatively small numbers—approximately 300,000 among four million Hispano-Romans—their elite status significantly shapes regional politics.

Ecclesiastical institutions, especially the Council of Bishops, emerge as stabilizing forces amid declining civil governance. Bishops, possessing both civil and religious authority, effectively maintain order, reinforcing Christianity’s growing influence as a social and political force.

Ostrogothic Ascendancy and Cultural Flourishing (448–459 CE)

In Italy, Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great emerges as a dominant figure, leading his Goths against Odoacer in 489 CE and establishing the Ostrogothic Kingdom by 493 CE. Theodoric's rule blends Roman administrative practices with Gothic leadership, ushering in stability and cultural revival, exemplified by artistic masterpieces like the mosaics in Ravenna’s mausoleum of Galla Placidia.

Late Imperial Decline, Visigothic Expansion, and Vandal Incursions (460–471 CE)

Between 456 and 460 CE, Vandals under Genseric briefly occupy coastal cities in Corsica and Sardinia, an occupation formalized by Emperor Majorian. Roman authority, weakened under emperors Majorian and Anthemius, struggles to maintain territorial integrity, but General Marcellinus, possibly supported by Pope Hilarius, regains control of these territories by 466 CE.

Simultaneously, Visigoths under King Euric consolidate power in southern Gaul and Iberia, gradually dismantling Roman administrative structures and paving the way toward medieval feudalism. Amid political upheaval, Christianity remains a powerful stabilizing and cultural force.

The Fall of Western Rome and Renewed Vandal Expansion (472–483 CE)

In 476 CE, the Western Roman Empire formally collapses with the deposition of Emperor Romulus Augustulus by the Germanic chieftain Odoacer. Concurrently, Visigothic King Euric expands his dominion, firmly establishing the Visigothic Kingdom across southern Gaul and Iberia.

Between 474 and 482 CE, Sardinia again falls under Vandal rule, possibly led by Huneric. Their control secures maritime trade routes between North Africa and the Mediterranean. Sardinian cities, notably Olbia, suffer destructive raids, reflecting the island’s strategic importance.

Theodoric’s Conquest, Ostrogothic Kingdom, and Vandal Administration (484–495 CE)

From 489 CE, Theodoric leads the Ostrogoths into Italy, defeating Odoacer by 493 CE and establishing the Ostrogothic Kingdom centered at Ravenna. Concurrently, Vandals maintain a structured administrative system in Sardinia, overseen by a praeses from Caralis, supported by procurators and tax officials. The territory is divided among crown lands and Vandal warriors, though local Sardinian-Roman landowners retain estates through payments, and Barbagia maintains semi-autonomous status.

Visigothic Consolidation and Frankish Rivalry (496–507 CE)

Under Alaric II, the Visigoths enact the Breviary of Alaric (506 CE), codifying Roman law for their subjects. However, rising tensions with the Franks culminate in Alaric’s defeat and death at the Battle of Vouillé (507 CE), forcing Visigoths into a defensive position within Iberia.

Stabilization and Reorganization (508–531 CE)

After Vouillé, the Visigothic Kingdom under Amalaric stabilizes, solidifying power in Iberia. In Italy, Theodoric’s Ostrogothic Kingdom experiences continued stability, economic prosperity, and cultural vitality, reflected in architectural achievements like the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo and Theodoric’s Mausoleum.

Cultural and Economic Continuity

Despite fragmentation, local economies adapt successfully, with robust agricultural production and active regional trade. Christianity shapes cultural norms, education, and artistic expression, preserving Roman traditions within evolving medieval contexts.

Germanic Influence and Legacy

The Suevi maintain a modest kingdom in northwestern Iberia, while the Vandals, despite limited numbers, imprint their legacy on southern Spain (Andalusia) and Sardinia, influencing regional names and historical memory.

Legacy of the Age

The era 388–531 CE signifies a critical transformation from classical Roman civilization to early medieval Europe. Visigothic and Ostrogothic kingdoms, empowered ecclesiastical structures, and cultural adaptations profoundly shape the region’s future identity. This period's enduring legacies include Roman-derived legal systems, ecclesiastical dominance, linguistic shifts (Romance languages), and foundational medieval political structures.

The western Roman emperor, Honorius (r. 395-423), because large parts of Spain are outside his control, commissions his sister, Galla Placidia, and her husband Ataulf, the Visigoth king, to restore order in the Iberian Peninsula, and he gives them the rights to settle in and to govern the area in return for defending it.

The highly romanized Visigoths manage to subdue the Suevi and to compel the Vandals to sail for North Africa.

In 484 they establish Toledo as the capital of their Spanish monarchy.

The Visigothic occupation is in no sense a barbarian invasion, however.

Successive Visigothic kings rule Spain as patricians who hold imperial commissions to govern in the name of the Roman emperor.

There are no more than three hundred thousand Germanic people in Spain, which has a population of four million, and their overall influence on Spanish history is generally seen as minimal.

They are a privileged warrior elite, though many of them live as herders and farmers in the valley of the Tagus and on the central plateau.

Hispano-Romans continue to run the civil administration, and Latin continues to be the language of government and of commerce.

Two Germanic tribes, the Vandals and the Suevi, cross the Rhine in 405 and ravage Gaul until the Visigoths drive them into Spain.

The Suevi establish a kingdom in the remote northwestern corner of the Iberian Peninsula.

The hardier Vandals, never exceeding eighty thousand, occupy the region that bears their name—Andalusia (Spanish, Andalucia).

At the end of the Antiquity period, ancient Gaul is divided into several Germanic kingdoms and a remaining Gallo-Roman territory, known as the Kingdom of Soissons, also known as the Domain of Syagrius.

Simultaneously, Celtic Britons, fleeing the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, settle the western part of Armorica.

As a result, the Armorican peninsula will be renamed Brittany, Celtic culture is revived and independent petty kingdoms arise in this region.

The pagan Franks, from whom the ancient name of "Francie" is derived, originally settle the north part of Gaul, but under Clovis I conquer most of the other kingdoms in northern and central Gaul.

In 498, Clovis I is the first Germanic conqueror after the fall of the Roman Empire to convert to Catholic Christianity, rather than Arianism; thus France is given the title "Eldest daughter of the Church" (French: La fille aînée de l'Église) by the papacy, and French kings will be called "the Most Christian Kings of France" (Rex Christianissimus).

The Franks embrace the Christian Gallo-Roman culture and ancient Gaul s eventually renamed Francia ("Land of the Franks").

The Germanic Franks adopt Romanic languages, except in northern Gaul where Roman settlements are less dense and where Germanic languages emerge.

Clovis makes Paris his capital and establishes the Merovingian dynasty, but his kingdom does not survive his death.

The Franks treat land purely as a private possession and divide it among their heirs, so four kingdoms emerge from Clovis's: Paris, Orléans, Soissons, and Rheims.

In 406 CE, the Iberian Peninsula is invaded by Germanic tribes, including the Vandals, Swabians, and Alans—the latter being a non-Germanic people of Iranian origin who had allied with the Vandals. Within two years, the invaders spread westward to the Atlantic coast.

The Swabians and Vandals in Hispania

The Swabians, primarily herders, are drawn to Galicia, where the climate resembles their homeland. Meanwhile, the Vandals settle north of Galicia but soon depart, taking with them the remnants of the Alans as they move eastward.

With the Vandals' departure, the Swabians migrate south, settling among the Luso-Romans, who offer no resistanceand gradually assimilate them.

Cultural and Administrative Shifts

Under Swabian influence, the urban life of the citanias fades, replaced by their customary rural settlement pattern—scattered houses and smallholdings—a land tenure system that persists in northern Portugal today.

As Roman administration collapses, the Swabians establish their capital in Braga, though ...

Atlantic Southwest Europe (388–531 CE): Transformation from Roman Province to Early Medieval Society

Between 388 and 531 CE, Atlantic Southwest Europe—encompassing northern and central Portugal, Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, and northern Spain south of the Franco-Spanish border (43.05548° N, 1.22924° W)—experienced profound transformation. Beginning with the late Roman Empire's gradual decline, the region transitioned through Germanic incursions, the establishment and consolidation of the Suebic Kingdom, Visigothic influences, and finally stabilized into an early medieval society characterized by regional autonomy, localized governance, resilient economies, and institutionalized Christianity.

Political and Military Developments

Collapse of Roman Authority and Germanic Settlement (388–411 CE)

-

Roman administrative structures steadily eroded following Emperor Theodosius I’s reign (d. 395 CE).

-

From 409 CE, the arrival of Germanic tribes (Suebi, Vandals, Alans) dramatically reshaped regional politics, with the Suebi establishing permanent settlements in Gallaecia (Galicia and northern Portugal).

Consolidation and Peak of Suebic Power (412–459 CE)

-

The Suebic Kingdom expanded and consolidated under kings Hermeric, Rechila, and Rechiar, reaching peak territorial control around 450 CE.

-

After King Rechiar’s defeat by the Visigoths in 456 CE, the Suebic Kingdom fractured but soon reorganized under new leadership, maintaining autonomy in Galicia and northern Portugal.

Visigothic Influence and Suebic Stability (460–495 CE)

-

Visigothic influence in Iberia intensified following the Battle of Órbigo (456 CE), though direct control over Atlantic Southwest Europe remained indirect.

-

The Suebi regained political stability under King Remismund (r. c. 464–469 CE), and later Veremund (469–508 CE), managing effective diplomatic relations with Visigothic neighbors and maintaining political autonomy.

Post-Visigothic Realignment and Suebic Autonomy (496–531 CE)

-

Following the Visigothic defeat at the Battle of Vouillé (507 CE), Visigothic political attention shifted southward to Toledo, further enhancing Suebic independence.

-

Under Theodemund (r. c. 508–550 CE), the Suebic Kingdom enjoyed sustained political stability, marking a definitive establishment of the region’s early medieval political structures.

Economic Developments

Resilient Local Economies and Ruralization

-

Despite political shifts, regional economies remained robust, centered on agriculture (grain, olives, vineyards), mining (silver, gold), livestock, and local manufacturing (pottery, textiles, metalwork).

-

Coastal settlements such as Olissipo (Lisbon) and Bracara Augusta (Braga) maintained moderate trade networks, though increasingly localized.

Villa-Based Economy and Early Feudal Structures

-

Rural fortified estates (villae) became dominant economic units, managed by local aristocrats and ecclesiastical leaders, clearly anticipating medieval feudal economies.

-

Major urban centers (Bracara Augusta, Emerita Augusta, and Asturica Augusta) retained administrative and ecclesiastical significance, though gradually eclipsed economically by rural estates.

Cultural and Religious Developments

Institutionalization of Christianity

-

Christianity solidified its position as the region’s dominant cultural and social force, with influential bishoprics (Braga, Emerita Augusta, Asturica Augusta) guiding local governance and community life.

-

Monastic communities grew significantly, becoming central to education, social welfare, agricultural innovation, and cultural preservation.

Arianism versus Chalcedonian Christianity

-

The Germanic Suebi initially embraced Arian Christianity, a doctrine emphasizing the subordinate nature of Christ relative to God the Father, creating significant religious distinctions with the local Romanized Iberian populations who adhered predominantly to Chalcedonian (Nicene) Christianity.

-

These theological differences initially fostered cultural and political tensions. However, over time, the Suebi began to shift towards Chalcedonian orthodoxy, gradually diminishing the religious divide. This religious integration significantly facilitated the blending of Germanic and Iberian cultures and strengthened ecclesiastical authority, culminating regionally in the later widespread adoption of Chalcedonian Christianity in the late 6th century.

Cultural Integration and Syncretism

-

The region saw extensive integration between Germanic settlers and Romanized Iberian, Celtic, and indigenous populations, resulting in distinctive cultural identities marked by rich syncretism.

-

Rural communities maintained unique forms of Christianity mixed with traditional indigenous beliefs, particularly in Galicia, Asturias, and northern Portugal.

Civic Identity and Governance

-

Civic identities became deeply localized, defined by religious affiliations, tribal traditions, and local governance rather than distant Roman or royal authorities.

-

Powerful local elites, bishops, and tribal leaders governed autonomously, establishing enduring regional identities and decentralized political structures.

Notable Tribal Groups and Settlements

-

Suebi: Central to the region’s political transformation, establishing a durable medieval kingdom in Galicia and northern Portugal.

-

Lusitanians, Vettones, Vaccaei: Maintained regional autonomy through skillful local governance and strategic diplomacy.

-

Gallaeci, Astures, Cantabri: Retained resilient indigenous traditions and local governance structures, pragmatically adapting to external influences.

-

Vascones: Remained autonomous and neutral, culturally distinctive, and politically independent, largely insulated from regional upheavals.

Long-Term Significance and Legacy

Between 388 and 531 CE, Atlantic Southwest Europe:

-

Transitioned decisively from Roman provincial systems into autonomous medieval polities, particularly evident in the consolidation of the Suebic Kingdom.

-

Established resilient villa-based economies and decentralized governance structures, directly shaping medieval feudal societies.

-

Deeply entrenched Christianity’s institutional influence, including the initial Arian–Chalcedonian divide, fundamentally shaping the region’s medieval cultural and social identities.

This transformative period laid enduring foundations for medieval Atlantic Southwest Europe, setting the stage for the region’s distinct historical, cultural, and political trajectory throughout the Middle Ages.

Over time, the city becomes known as Portucale, a combination of portus (port) and Cale. This name eventually extends to the surrounding territory on both banks of the Douro River, laying the foundation for the future name of Portugal.

By 415 CE, with much of the Iberian Peninsula slipping beyond their control, the Romans commission the Visigoths—the most highly Romanized of the Germanic peoples—to restore Roman authority in Hispania.

The Visigothic Intervention

The Visigoths successfully expel the Vandals, forcing them to sail for North Africa, and defeat the Swabians in what is now Portugal and Galicia. Despite these conquests, both the Swabian kings and their Visigothic overlords continue to govern under imperial commissions, meaning their kingdoms remain nominally part of the Roman Empire. Latin remains the language of administration and commerce, ensuring a degree of continuity in governance.

The Rise of the Visigothic Kingdom

Having converted to Christianity in the fourth century, the Visigoths eventually establish an independent kingdom with its capital at Toledo. Their monarchy is absolute, with each sovereign elected by an assembly of nobles.

To reinforce their rule, Visigothic kings convene great councils composed of bishops and nobles, who assist in deciding both ecclesiastical and civil matters—a practice that strengthens the political and religious structure of the kingdom.

Fusion of Cultures and the Kingdom’s Legacy

Over time, the Visigoths, Swabians, and Hispano-Romans gradually merge into a unified politico-religious entity, forming the foundation of medieval Iberian civilization. This kingdom will endure until the eighth century, when the Muslim conquest reshapes the Iberian Peninsula.

Atlantic West Europe (388–531): From Roman Gaul to Frankish Dominance

Between 388 and 531, Atlantic West Europe—covering the regions of northern and central France, including Aquitaine, Burgundy, Alsace, the Low Countries, and the Franche-Comté—underwent profound transformations. This period marked the decline of Roman authority, the migration and settlement of Germanic peoples, the rise of powerful Frankish kingdoms, and the increasing influence of the Catholic Church.

Political and Military Transformations

-

Late Roman Authority (388–410)

-

Stability under Emperor Theodosius I (r. 379–395) gave way to political uncertainty following his death.

-

The usurper Constantine III temporarily seized control of Gaul, leading to weakened Roman defenses and vulnerability to barbarian incursions.

-

-

Barbarian Migrations and Kingdoms (411–450)

-

Visigoths, Burgundians, and Franks established independent realms within former Roman territories.

-

The Visigoths, granted territory as Roman foederati, expanded into Aquitaine and established Toulouse as their capital.

-

The Burgundians established themselves along the Rhône Valley, creating a kingdom centered at Lyon.

-

-

The Rise of the Merovingians (451–481)

-

The Battle of the Catalaunian Plains (451), led by Roman general Aetius with Visigothic and Frankish allies, halted Attila the Hun’s westward advance.

-

Merovingian Franks under Childeric I consolidated power around Tournai, laying the groundwork for Frankish dominance.

-

-

Frankish Consolidation under Clovis (482–511)

-

Clovis united the Frankish tribes, defeated Syagrius, the last Roman ruler in Gaul (486), and expanded his territory significantly.

-

His conversion to Catholicism (c. 496) secured the support of the Gallo-Roman populace and the Catholic Church.

-

The decisive defeat of the Visigoths at Vouillé (507) significantly expanded Frankish control into Aquitaine.

-

-

Division and Expansion (512–531)

-

Upon Clovis’s death in 511, his sons—Theuderic, Chlodomer, Childebert, and Chlothar—divided the Frankish kingdom, each ruling semi-autonomous territories.

-

Continued Frankish expansion culminated in the conquest and integration of Burgundy by 534.

-

Economic and Social Developments

-

Decline and Transformation of Urban Life

-

Roman urban centers deteriorated; trade networks weakened as imperial structures collapsed.

-

Increasing ruralization occurred, with populations moving toward countryside estates and fortifications, heralding medieval rural feudal society.

-

-

Shifts in Economic Foundations

-

A transition from Roman monetary economy to more localized, agrarian economies took place, emphasizing landholdings and agricultural production.

-

The foundation for medieval manorial systems was established as local elites consolidated rural power.

-

Religious and Cultural Developments

-

Growth of Ecclesiastical Authority

-

Bishops, notably figures like Sidonius Apollinaris (bishop of Clermont), assumed greater civil and religious authority, managing civic affairs amid declining Roman administration.

-

Councils, such as the Council of Agde (506), standardized ecclesiastical practices and reinforced Catholic dominance in the region.

-

-

Spread and Consolidation of Catholicism

-

The collapse of Arian Visigothic power in Gaul solidified Catholicism’s religious supremacy.

-

Monasticism expanded, preserving classical texts and cultural traditions, laying foundations for medieval intellectual life.

-

Legacy and Significance

By 531, Atlantic West Europe had fundamentally shifted from Roman governance to fragmented barbarian kingdoms and ultimately to consolidated Frankish rule under the Merovingians. Clovis's unification efforts and strategic religious alignment firmly established the Catholic Frankish kingdom as the predominant power, creating cultural and political legacies that defined medieval European history.

The Frankish Expansion and the Unification of the Low Countries

With the collapse of Roman rule in the Low Countries, the Franks expand their influence, establishing multiple small kingdoms across the region.

By the 490s, Clovis I consolidates these territories in the southern Netherlands, forging a single Frankish kingdom. From this stronghold, he launches further conquests into Gaul, laying the foundations for what will become the Frankish dominion over much of Western Europe.

As the Franks migrate southward, many gradually adopt the Vulgar Latin spoken by the local Gallo-Roman population, a linguistic shift that will contribute to the emergence of early Romance languages in the region.