Central Asia (1108 – 1251 CE): Khwarazmian …

Years: 1108 - 1251

Central Asia (1108 – 1251 CE): Khwarazmian Rise, Karakhanid Decline, and Mongol Conquest

Geographic and Environmental Context

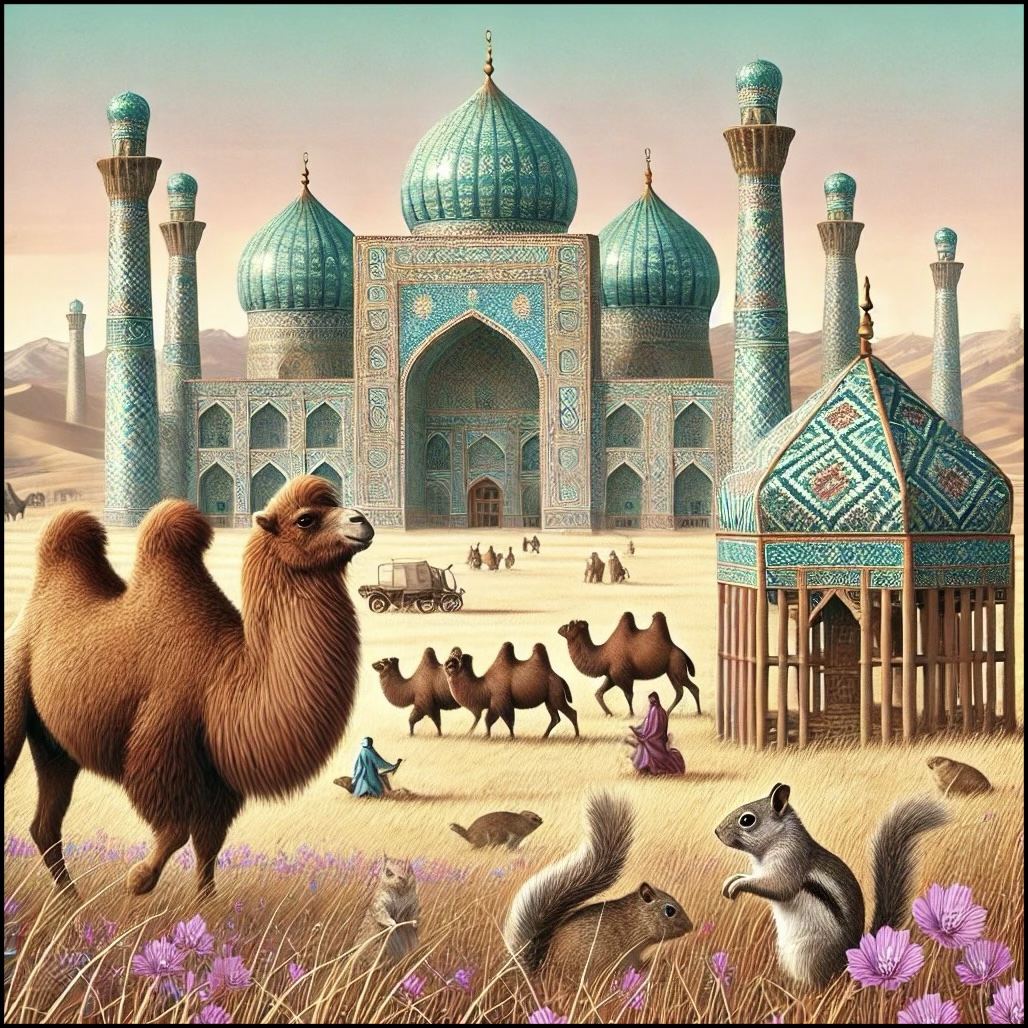

Central Asia includes the Syr Darya and Amu Darya basins (Transoxiana), Khwarazm, the Ferghana Valley, the Merv oasis and Kopet Dag piedmont, the Kazakh steppe to the Aral–Caspian lowlands, and the Tian Shan–Pamir margins.

-

The oasis belts of Bukhara, Samarkand, Khwarazm (Urgench), and Merv anchored dense settlement and irrigation systems.

-

The Kazakh steppe supported nomadic confederations of Kipchaks and later Mongols.

-

The Tian Shan and Pamir mountains framed caravan routes linking the Tarim Basin with Transoxiana.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

The Medieval Warm Period favored pastoral productivity on the steppe and sustained agriculture in irrigated oases.

-

Variability in river flow from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya affected irrigation, requiring constant maintenance.

-

Pastoralists and oasis farmers relied on exchange to balance environmental uncertainty.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Karakhanids (10th–12th centuries): Fragmented into western and eastern branches; power waned after the early 12th century.

-

Khwārazm-Shahs: Rose from Seljuk-appointed governors to powerful rulers. By the early 13th century, the Anushteginid dynasty expanded Khwarazm into an empire spanning Transoxiana, Khurasan, and Iran.

-

Seljuks: Still influential in Persia and Khurasan early in this period, but their authority in Central Asia eroded.

-

Kara-Khitai (Western Liao, 1124–1218): A Khitan successor state from Manchuria, they dominated much of Central Asia until overthrown by Khwarazm and Mongols.

-

Mongol Conquest: From 1219–1221, Chinggis Khan’s armies devastated Central Asia, sacking Bukhara, Samarkand, Merv, and Nishapur, toppling the Khwarazm-Shahs. By 1251, Central Asia was reorganized under Mongol rule as part of the empire’s Chagatai Ulus.

Economy and Trade

-

Oasis agriculture: wheat, barley, cotton, fruits, and melons formed the basis of settled economies.

-

Pastoral economies of Kipchak and other steppe nomads supplied horses, livestock, and military manpower.

-

Silk Road trade flourished: caravans carried silks, spices, ceramics, and precious metals between China, Persia, and the Mediterranean.

-

Khwarazm’s position at the Oxus delta made it a commercial hub for east-west and north-south trade.

-

The Mongol invasions disrupted but later reorganized Silk Road networks under imperial oversight.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Qanats and irrigation canals sustained oasis farming; cotton production expanded.

-

Brick and glazed tile architecture flourished in mosques, madrasas, and caravanserais.

-

Seljuk and Khwarazmian military relied on cavalry, bows, and heavy armor, while Mongols introduced highly disciplined cavalry organization.

-

Nomads used felt tents (yurts), portable and adapted to steppe life.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

The Silk Road through Samarkand, Bukhara, and Kashgar remained the key east-west artery.

-

Steppe corridors linked Kipchak and Mongol nomads with Eastern Europe, Persia, and China.

-

The Oxus and Syr Darya valleys integrated highland, steppe, and desert zones.

-

Pilgrimage and intellectual networks tied Central Asia to Khurasan, Persia, and the Islamic world.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Islam (Sunni, Hanafi) was the dominant religion in the oases, supported by mosques, madrasas, and Sufi orders (Yasawiyya, Kubrawiyya).

-

Sufism spread widely, with shrines and saints reinforcing Islam in both urban and rural areas.

-

Steppe nomads practiced shamanistic traditions, though Islam spread gradually among Kipchaks.

-

Mongol rulers at first remained shamanists, but tolerated diverse religions in their conquered territories.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Agricultural and pastoral symbiosis created resilience in the face of climatic fluctuation.

-

Trade wealth underpinned Khwarazmian prosperity but also made oases vulnerable to invasion.

-

Religious institutions and Sufi orders preserved community identity during political upheavals.

-

The Mongol conquest devastated cities but later re-established order under imperial trade systems.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251 CE, Central Asia had been reshaped by the rise and fall of Khwarazm and the Mongol conquest. Once a hub of flourishing Islamic culture and Silk Road commerce, the region was now integrated into the Mongol Empire, under the Chagatai Ulus. The blending of Islamic scholarship, nomadic traditions, and imperial reorganization made Central Asia pivotal to Eurasian connectivity in the 13th century.

Central Asia (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

People

Groups

- Polytheism (“paganism”)

- Buddhism

- Khwarezm

- Margiana

- Khitan people

- Buddhism, Mahayana

- Christians, Eastern (Diophysite, or “Nestorian”) (Church of the East)

- Islam

- Muslims, Sunni

- Sufism

- Kara-Khanid Khanate

- Kipchaks

- Khwarezm dynasty

- Seljuq Empire, Western capital

- Seljuq Empire, Eastern capital

- Kara-Khitan Khanate

- Mongol Empire

- Khwarezm dynasty

- Khwarezm dynasty

- Khwarezmians

- Khwarezm dynasty

Topics

- Medieval Warm Period (MWP) or Medieval Climate Optimum

- Mongol Conquests

- Mongol invasion of Khwarezmia and Eastern Iran

- Mongol Invasion of Central Asia

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Fibers

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Lumber

- Money

- Manufactured goods

- Spices