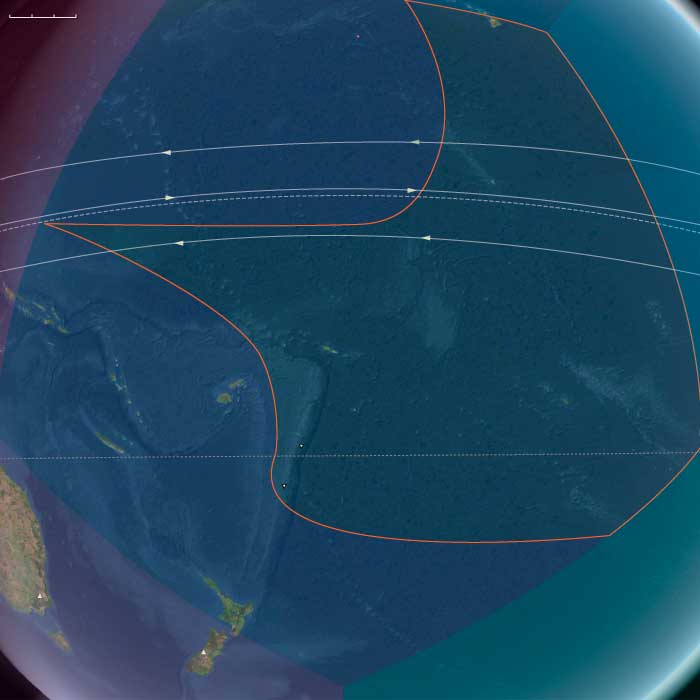

Bougainville sees islands of the Tuamotu group …

Years: 1767 - 1767

March

Locations

People

- Jeanne Baret

- Louis XV of France

- Louis-Antoine de Bougainville

- Philibert Commerson

- Pierre-Antoine Véron

- Samuel Wallis

Groups

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 12 total

Atlantic Southwest Europe (1840–1851): Liberal Conflicts, Regional Unrest, and Early Industrialization

Between 1840 and 1851, Atlantic Southwest Europe—including northern and central Portugal, Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, northern León and Castile, northern Navarre, northern Rioja, and the Basque Country—experienced intense liberal conflicts, social and economic transformations, and regional tensions. This era saw the climax and resolution of the Patuleia Revolt in Portugal, continuing economic change through early industrialization, and deepening struggles over governance, liberal reform, and local autonomy in both Spain and Portugal.

Political and Military Developments

Portugal: Patuleia and its Aftermath (1846–1847)

-

The Patuleia Revolt (1846–1847), a popular uprising particularly intense around Porto and northern regions, erupted against Prime Minister Costa Cabral's authoritarian centralization, taxation, and disregard for regional interests.

-

With Porto as their stronghold, rebels formed an alternative liberal government, provoking significant military engagements.

-

The conflict was resolved through international mediation by Britain and Spain with the Convention of Gramido (June 1847), restoring relative political balance, forcing Cabral’s resignation, and tempering central authority.

Spain: Moderates, Progressives, and Carlism

-

Spain faced ongoing struggles between Moderate Liberals (Moderados) favoring centralized constitutional monarchy and the Progressive Liberals (Progresistas) seeking broader democratic reforms. Political instability resulted in frequent changes of government.

-

Northern Spain—especially the Basque Country, Navarre, and parts of Catalonia—continued as sites of Carlism, whose supporters promoted traditional monarchy, the Church, and regional fueros (autonomy privileges). Despite military defeat in the earlier First Carlist War (1833–1840), Carlism remained politically active and influential, especially in Navarre, the Basque provinces, and rural areas of northern Castile and León.

Economic Developments: Early Industrialization and Maritime Growth

Portugal’s Maritime and Commercial Activity

-

Porto expanded significantly through increased export of Port wine and textiles, primarily to British markets. Improved port facilities and infrastructure facilitated increased maritime commerce.

-

Industrialization slowly advanced, especially in northern Portuguese cities like Braga and Guimarães, where textile manufacturing industries modernized production methods, increasing economic prosperity and urban employment.

Northern Spain’s Industrialization

-

The Basque Country (Bilbao) and Cantabria (Santander) saw sustained industrial growth driven by iron production, shipbuilding, and expanding trade links with Britain and France.

-

Galicia strengthened its maritime economy through fisheries, shipping, and trade expansion, notably from ports such as Vigo and A Coruña. Improved communication routes supported modest industrial growth in Galicia, Asturias, and northern León.

Social and Urban Developments

Urban Expansion and Social Tensions

-

Major urban centers (Porto, Bilbao, Santander, Braga, Vigo) continued rapid growth, reflecting industrial employment opportunities and rural migration. Social inequalities became increasingly pronounced, fueling tensions between industrial elites and working classes.

-

Social unrest in cities like Porto, Vigo, and Bilbao highlighted urban inequalities, leading to periodic labor strikes and demonstrations demanding improved working conditions, wages, and political representation.

Rural Hardships and Emigration

-

Galicia, Asturias, and northern Castile faced persistent rural poverty, agricultural stagnation, and population pressures. These conditions spurred significant emigration to the Americas (especially Brazil, Argentina, and Cuba), marking early stages of mass Iberian emigration.

Cultural and Religious Developments

Liberalism, Education, and Secularization

-

Liberal ideals continued reshaping education and intellectual life. Universities in Coimbra and Porto (Portugal), Santiago de Compostela (Galicia), and Salamanca (Castile) emphasized liberal education, secular studies, and scientific innovation, influencing educated elites and urban middle classes.

-

Despite secularization trends, Catholicism remained socially dominant, with the Church strongly influencing rural populations, especially evident in the Basque Country, Navarre, and northern Portugal.

Cultural Flourishing and Regional Identities

-

Regional literature, arts, and language revival movements flourished. Galicia saw renewed interest in Galician language and folklore; northern Portugal embraced literary Romanticism; the Basque Country nurtured distinct cultural pride through language and traditions.

-

Artistic patronage in cities such as Porto, Bilbao, and Santiago de Compostela supported growing cultural identity and reinforced local autonomy movements.

Legacy and Significance

The years 1840–1851 in Atlantic Southwest Europe marked critical transitions toward greater regional autonomy, moderate liberal reforms, and early stages of industrialization. Portugal’s Patuleia Revolt underscored tensions between centralization and regional interests, while Spain’s ongoing liberal-Carlist conflicts reflected deeper ideological divides. Economic growth and urbanization brought prosperity but heightened social inequalities and prompted rural emigration. Cultural developments reinforced regional identities, laying critical foundations for future political and social transformations across the region.

The Septemberist Rule and the Costa Cabral Coup (1836–1841) – The Restoration of the Charter

The Septemberists, the radical liberals who had come to power during the Setembrismo Revolution of 1836, held office until June 1841, when they were removed in a bloodless coup by moderates. This coup d’état, led by António Bernardo da Costa Cabral, resulted in the abolition of the 1838 Constitution and the restoration of the Constitutional Charter of 1826.

Costa Cabral’s Coup and the Return of the Moderates (June 1841)

- In June 1841, Costa Cabral and the moderate (Charterist) faction staged a bloodless coup, removing the Septemberist government from power.

- The 1838 Constitution was abolished, and the Constitutional Charter of 1826 was reinstated, returning Portugal to a more conservative constitutional monarchy.

- Costa Cabral, who had organized and led the coup, took charge of the government and began implementing ambitious political, economic, and social reforms.

Costa Cabral’s Reforms and Growing Opposition

As Portugal’s new leader, Costa Cabral sought to modernize the country, introducing progressive reforms, but these measures provoked widespread resistance, especially in the countryside.

Reforms Introduced by Costa Cabral

- Sanitary Regulations – New public health policies, including prohibiting burials in churchyards, were introduced to improve sanitation and prevent disease outbreaks.

- Infrastructure Projects – Investments in roads, bridges, and public works to modernize Portugal’s economy.

- Administrative Reorganization – Centralized governance and tightened control over municipalities, reducing local autonomy.

- Judicial and Fiscal Reforms – Efforts to streamline tax collection and modernize the legal system.

Miguelist Backlash – Resistance in Rural Portugal

- The rural population, still largely Miguelist (absolutist), reacted strongly against the new liberal government in Lisbon.

- The prohibition of burials in churchyards particularly outraged religious conservatives, as traditional burial practices were deeply tied to Catholic customs.

- The clergy and local nobility stirred up resistance, portraying Costa Cabral’s reforms as an attack on religion and local traditions.

- This discontent would later escalate into the Maria da Fonte Revolt of 1846, a major rural uprising against the liberal regime.

Conclusion – A Fragile Return to Moderation

Costa Cabral’s coup and subsequent reforms marked the return of moderate Charterist rule, but his policies alienated the rural population, setting the stage for further instability. While his government sought to modernize Portugal, it ultimately provoked resistance that would culminate in renewed political conflict in the mid-1840s.

The Maria da Fonte Revolt and the Septemberist Uprising (1846–1847) – The Last Liberal Conflict in Portugal

By the mid-19th century, Portugal remained politically unstable, with factions of liberals—moderates (Chartists) and radicals (Setembristas)—continuing to struggle for control. This instability erupted into the Maria da Fonte Revolt (1846) and the subsequent Septemberist Uprising (1846–1847), pushing the country to the brink of another civil war.

The Maria da Fonte Revolt (April–May 1846)

- The Maria da Fonte movement originated in Minho, where women traditionally played a key role in churchyard burials.

- When Prime Minister Costa Cabral imposed new cemetery regulations, restricting traditional Catholic burial practices, rural women and their communities protested against what they saw as an attack on their religious customs.

- The protests grew into an armed rural revolt, spreading throughout the north of Portugal, supported by the rural nobility and clergy.

- Costa Cabral’s government, unable to suppress the revolt, collapsed on May 20, 1846.

The Political Crisis – A Divided Government and the Septemberist Uprising

- The new government, led by the Duke of Palmela, was a fragile coalition of radicals and moderates.

- To calm tensions, the government rescinded the cemetery regulations.

- However, Palmela’s decision to call for new elections in October 1846 to unite the moderates triggered a backlash from the radicals (Septemberists).

The Septemberist Uprising (October 1846 – June 1847)

- The Septemberists, strongest in Porto, revolted against the government, establishing a provisional junta.

- The new Prime Minister, the Duke of Saldanha, attempted to suppress the uprising, but it spread beyond Porto to other regions.

- With Portugal on the verge of another civil war, Queen Maria II turned to the Quadruple Alliance (Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal’s liberal factions) for support.

The Intervention of the Quadruple Alliance (1847) and the End of the Crisis

- The Quadruple Alliance imposed a naval blockade on Portugal and sent troops, forcing the Septemberists to surrender.

- On June 29, 1847, a peace agreement was signed, ending the conflict.

- Saldanha resigned, and Costa Cabral returned to power, marking the end of the Septemberist challenge.

Conclusion – The Last Liberal Civil Conflict in Portugal

The Maria da Fonte Revolt and the Septemberist Uprising were the last major liberal conflicts in Portugal, showing the deep divide between radicals and moderates even after the Liberal Wars. Although Costa Cabral’s return signified a victory for the moderates, political instability and factional struggles would continue to shape Portugal’s political landscape throughout the 19th century.

The Regeneration of Portugal (1851) – Saldanha’s Coup and the Path to Stability

After years of political instability and factional struggles, Marshal João Carlos de Saldanha staged a successful revolt in 1851, ousting Costa Cabral and gaining control of the government. This event marked the beginning of the Regeneração (Regeneration), a period of political reform and gradual stabilization in Portugal.

Saldanha’s Revolt and the Fall of Costa Cabral (1851)

- Saldanha, with the support of the Porto garrison, launched a coup, taking control of the government.

- Costa Cabral was sent into exile, ending his divisive and authoritarian rule.

- The Regeneradores (Regenerators), Saldanha’s faction, sought to modernize and adapt the Constitutional Charter of 1826 to make it more compatible with Portugal’s evolving political and social reality.

Reforming the Constitutional Charter – The Regeneration Period

- Rather than abolishing the Constitutional Charter, the Regenerators pursued gradual modifications, introducing amendments to make the system more inclusive.

- The first major reform was a new electoral law, which:

- Expanded voting rights, making the franchise more acceptable to the Septemberists (the radical liberals).

- Allowed for broader political participation, reducing tensions between factions.

- Over time, these reforms stabilized Portuguese governance, ensuring a more balanced constitutional monarchy.

The Evolution of Political Factions – The Rise of the Progressives

- The Septemberists, who had historically opposed the Charterist moderates, began evolving into a new political identity.

- They were now referred to as the Históricos (Historicals) and, later, as the Progressistas (Progressives).

- This shift in political dynamics allowed for a more structured two-party system, reducing the constant revolts and factional conflicts of previous decades.

Conclusion – A More Stable Portugal

Saldanha’s Regeneration movement marked a turning point in Portuguese politics, shifting from violent factional struggles to a more gradual process of reform. By modifying the Constitutional Charter rather than overthrowing it, Portugal achieved a degree of stability, allowing the country to move toward a more functional constitutional monarchy in the second half of the 19th century.

The Revolution of Maria da Fonte (1846–1847)

The Revolution of Maria da Fonte, also known as the Revolution of the Minho, erupted on May 16, 1846, as a popular uprising against the Cartista government of Portugal, led by António Bernardo da Costa Cabral, 1st Marquess of Tomar. This widespread revolt, rooted in deep-seated social tensions left unresolved after the Liberal Wars, was further inflamed by unpopular policies, including new military recruitment laws, fiscal alterations, and the prohibition of burials inside churches—a measure that struck at the heart of local religious and cultural traditions.

Originating in Póvoa de Lanhoso in the Minho region, the uprising quickly gained momentum, spreading across northern Portugal. At the center of the initial unrest was a woman named Maria, a native of Fontarcada, whose leadership and defiance earned her the name Maria da Fonte. The insurrection’s early phase saw significant female participation, leading to the revolt itself being named in her honor.

Despite its intensity and broad support, the revolution was ultimately crushed by royalist troops on February 22, 1847, reaffirming the government’s authority but leaving lasting political and social repercussions in its wake.

The Spread of the Uprising and the Patuleia Civil War (1846–1847)

Following its initial outbreak in Minho, the Revolution of Maria da Fonte soon spread to the rest of Portugal, forcing the dismissal of António Bernardo da Costa Cabral. In his place, Pedro de Sousa Holstein, 1st Duke of Palmela, was appointed as head of a new government in an attempt to restore stability.

However, the situation took a dramatic turn on October 6, 1846, when Queen Maria II, in a palace coup known as the Emboscada (Ambush), abruptly dismissed the Palmela government. In its stead, she appointed Marshal João Francisco de Saldanha Oliveira e Daun, 1st Duke of Saldanha, a move that reignited the insurrection.

The resulting conflict escalated into a full-scale civil war, known as the Patuleia, lasting for eight months. The war ultimately ended with the Convention of Gramido, signed on June 30, 1847, following the intervention of foreign military forces from the Quadruple Alliance. This resolution, imposed by Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal’s own loyalist factions, reasserted royal authority while further entrenching the political divisions that had plagued the nation since the Liberal Wars.

The Patuleia Revolt (1846–1847): Portugal’s Liberal Civil Conflict

Overview

The Patuleia Revolt, also known as the Little Civil War, was a significant but brief conflict fought primarily between October 1846 and June 1847. It emerged from deep-seated political tensions in Portugal, characterized by liberal divisions, regional grievances, and widespread popular unrest, particularly strong in the northern regions around Porto, Braga, and the province of Minho.

Causes and Background

-

Political Division and Authoritarian Rule:

The immediate trigger was the authoritarian and highly centralizing governance of António Bernardo da Costa Cabral, who as prime minister (1842–1846) initiated extensive modernization but alienated various liberal factions by concentrating power, limiting political freedoms, and implementing unpopular tax reforms. -

Economic Hardship and Rural Unrest:

Northern Portugal—economically reliant on agriculture, wine exports, and local industry—suffered under heavy taxation and limited investment in rural areas. Costa Cabral's policies disproportionately benefited the Lisbon elite, fueling resentment and fostering support for opposition groups in northern communities. -

Liberal Ideological Split:

The revolt intensified pre-existing ideological divisions among liberals. While the "Cabralistas" (supporters of Costa Cabral) favored centralization and state-driven modernization, the "Setembristas" (Septemberists, more radical liberals) and other dissident factions demanded constitutional reforms, decentralization, and greater popular representation.

Course of the Conflict

-

Outbreak of Revolt (October 1846):

Sparked initially by popular protests in the northern city of Braga against centralization and heavy taxation, the revolt quickly spread throughout northern Portugal, with particularly intense fighting around Porto, which became the rebel stronghold. -

Popular Participation and Mobilization:

The conflict earned the nickname "Patuleia" from the Portuguese colloquial term "pata-ao-léu" (barefoot or ragged people), referencing the revolt's grassroots character, with broad participation from peasants, artisans, and urban laborers. -

Porto as Rebel Stronghold:

Porto became the center of resistance, establishing an alternative government that openly challenged Lisbon's authority. Intense military engagements occurred around Porto, Braga, and throughout the Minho region, causing significant disruptions to economic activity. -

International Intervention (British and Spanish Mediation):

To prevent Portugal from slipping into prolonged instability, Britain and Spain—both deeply concerned about Iberian stability and regional balance—intervened diplomatically. Their mediation sought to restore stability quickly and efficiently.

Resolution and Outcome: The Convention of Gramido (June 1847)

-

The conflict ended with the Convention of Gramido (signed June 29, 1847), brokered by Britain and Spain, which imposed a negotiated peace:

-

Costa Cabral’s resignation from power was a key condition.

-

A general amnesty for most rebels was granted.

-

Authority was restored to a more moderate and inclusive government in Lisbon, balancing regional interests more carefully.

-

-

Although the rebels failed to achieve all of their demands—particularly extensive decentralization—the conflict weakened centralized authoritarianism and set Portugal on a slightly more balanced political course, acknowledging regional and popular concerns.

Legacy and Significance

-

Political Balance:

The Patuleia marked a significant turning point, moderating central authority, tempering extreme liberal factions, and highlighting the importance of regional interests in national governance. -

Regional Empowerment and Identity:

The revolt underscored northern Portugal’s distinct political identity, emphasizing regional autonomy, economic concerns, and local governance. -

Influence on Future Portuguese Politics:

The event set an important precedent for future political compromises, highlighting the delicate interplay between centralized government power and regional interests, a theme recurring throughout nineteenth-century Portuguese politics.

Ultimately, the Patuleia Revolt illustrated the profound complexity of liberal politics in Portugal, the deeply rooted nature of regional grievances, and the critical role played by popular participation in shaping the country's political trajectory.

Political Dynamics in Portugal: The Regenerators, the Progressives, and Rotativismo

In 19th-century Portugal, the Regenerators and Progressives were not political parties in the modern sense but rather loose coalitions of influential figures, or notables, bound by personal loyalties and local interests. With an electorate comprising less than one percent of the population, these factions functioned as elite-controlled networks, ensuring that political power remained in the hands of a small ruling class.

Elections were not competitive in the contemporary democratic sense. Instead, they were typically held after a change in governing factions, designed primarily to grant the incoming government a parliamentary majority. By tacit agreement, the ruling faction would remain in power as long as it was able, before voluntarily handing over governance to the opposition.

After 1856, this system of alternating rule, known as rotativismo, became institutionalized, ensuring a predictable cycle of power that provided political stability. While rotativismo prevented the kind of violent political conflicts seen elsewhere in Europe, it also restricted meaningful political participation and delayed broader democratic reforms. The system would remain largely intact until the end of the 19th century, when increasing social and political pressures began to challenge its viability.

The Janeirinha Revolt and the End of the Regeneration (1868)

The Janeirinha Revolt, a protest movement against the tax on consumables, erupted on January 1, 1868, triggering immediate political upheaval and significant administrative reforms in Portugal. The movement gained widespread support in major cities, particularly Lisbon, Porto, and Braga. A large demonstration in Porto on January 1, 1868, as part of the uprising, led to the founding of the newspaper O Primeiro de Janeiro, named in commemoration of the event.

The revolt swiftly led to the fall of the government on January 4, 1868, resulting in the appointment of a new administration under António José d’Ávila. For many historians, the Janeirinha marked the end of the Regeneration, a political era that had brought relative stability to the Portuguese Constitutional Monarchy.

The Regeneration and Its Legacy (1851–1868)

The Regeneration (Regeneração) had begun following the military insurrection of May 1, 1851, which had led to the fall of Costa Cabral and the Septembrist government. Though initially led by Marshal João Carlos de Saldanha, the era’s defining figure was Fontes Pereira de Melo, who championed economic development and modernization, albeit through heavy fiscal policies that ultimately provoked public discontent.

While the Regeneration lacks a precise chronological boundary, it lasted for approximately seventeen years, shaping Portugal’s economic and infrastructural landscape. However, the Janeirinha Revolt not only led to the fall of the government but also reshaped Portugal’s political forces, leading to:

- The formation of the Reformist Party, which altered the country’s political dynamics.

- The onset of prolonged governmental instability, as political factions became increasingly fragmented.

- The definitive end of the stability imposed by the "Regenerador" movement, ushering in a more volatile period of governance.

Thus, while the Regeneration had been a period of progress and modernization, it ultimately fell victim to the fiscal burdens it had imposed, as growing dissatisfaction culminated in the Janeirinha Revolt, changing the course of Portuguese politics.

Years: 1767 - 1767

March

Locations

People

- Jeanne Baret

- Louis XV of France

- Louis-Antoine de Bougainville

- Philibert Commerson

- Pierre-Antoine Véron

- Samuel Wallis