Antarctica (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene …

Years: 7821BCE - 6094BCE

Antarctica (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Ice Retreat, Blue Shadows, and the Rebirth of Polar Life

Geographic & Environmental Context

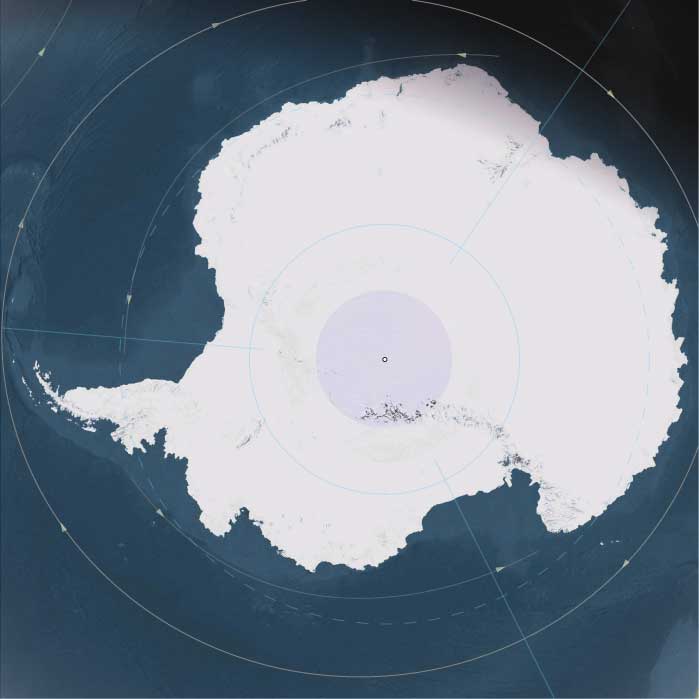

In the Early Holocene, Antarctica was a continent in transition—from the crushing grip of the last glacial maximum toward the cold equilibrium that would define the modern world.

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet remained massive and largely stable, locked high across the polar plateau.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet, however, was in full retreat: ice fronts pulled back across the Ross and Weddell embayments, and outlet glaciers in the Amundsen Sea sector began their long withdrawal.

Ice-free oases and mountain ridges—Bunger Hills, McMurdo Dry Valleys, Larsemann Hills, and portions of the Antarctic Peninsula—expanded modestly, exposing ancient moraines, saline lakes, and tundra-like niches.

Around the margins, the Southern Ocean encircled the continent as a restless engine—driven by the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC)—linking it ecologically to the subantarctic islands of the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal maximum brought slight but critical warming to the polar realm:

-

Mean annual temperatures rose by a few degrees compared to the Late Glacial period.

-

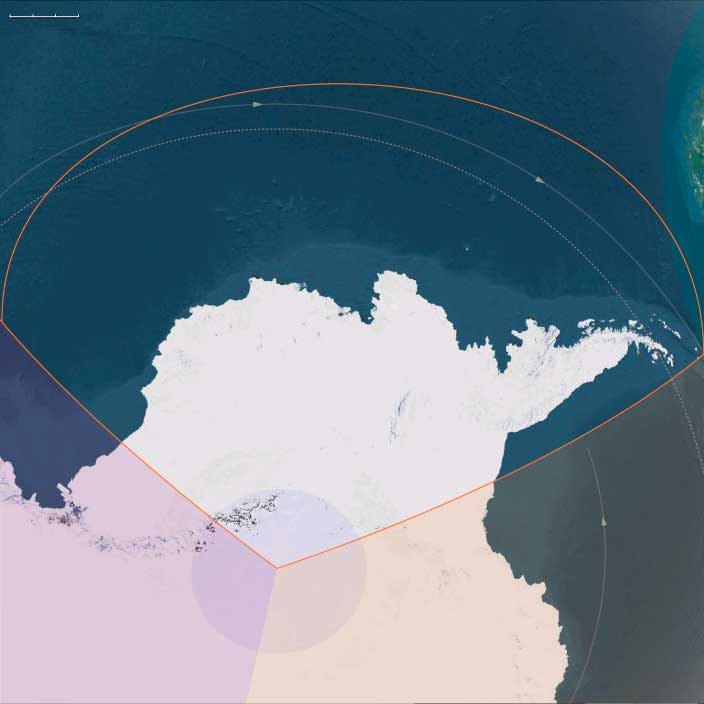

Ice-sheet thinning occurred along coasts and embayments; major ice shelves (Ross, Filchner–Ronne, Amery) receded inland from their glacial maxima but remained expansive.

-

Sea ice diminished seasonally, producing longer open-water summers; polynyas (persistent open-water zones) formed near coasts.

-

Moisture transport from mid-latitude storms increased snowfall in coastal sectors, while the interior remained hyper-arid and katabatic-wind-swept.

The Antarctic atmosphere, once dominated by glacial cold, now cycled through new seasonal pulses of thaw, meltwater, and refreeze—introducing rhythm to a continent that had long known only permanence.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human beings had yet set foot on the Antarctic continent.

Life here was purely non-human, yet in its own way as adaptive and dynamic as any civilization:

-

Coastal tundra oases supported mosses, lichens, and microbial mats, expanding in meltwater-fed basins and rock fissures.

-

Seabirds and penguins (Adélie, gentoo, chinstrap) colonized ice-free shores, while petrels, skuas, and cormorants nested along the Antarctic Peninsula.

-

Seals (Weddell, leopard, and elephant) established new haul-outs on beaches newly exposed by ice retreat.

-

Offshore ecosystems surged with life: krill, squid, fish, and plankton fed vast congregations of whales returning to the high-latitude feeding grounds each summer.

This was the rebirth of the polar food web—a return of productivity after millennia of glacial austerity.

Technology & Material Culture

In the human world elsewhere, people were perfecting pottery, domesticating animals, and building the first agricultural villages—but Antarctica remained untouched.

No hearth, no track, no artifact broke its frozen solitude; the continent’s only “technology” was that of ice, wind, and wave shaping the living crust of sea and shore.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

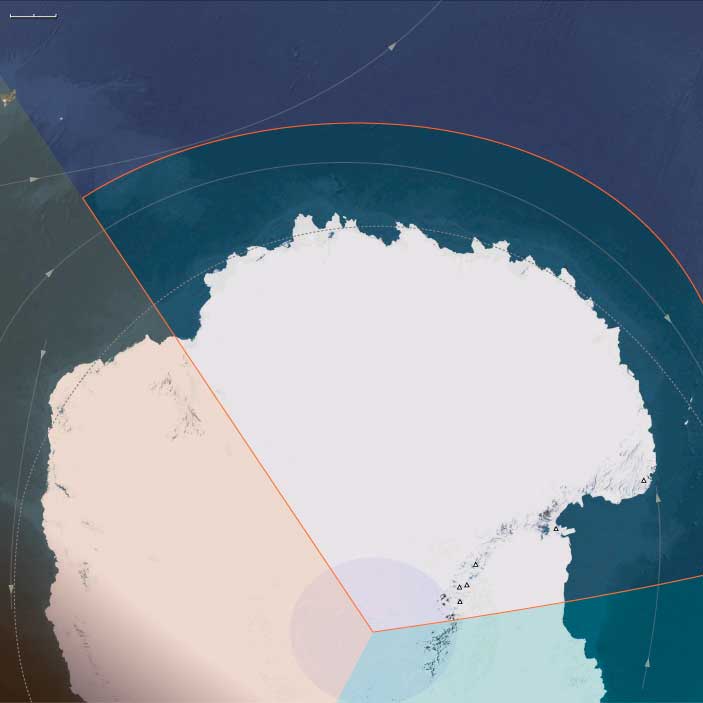

Biological movement replaced any human route:

-

The ACC circled Antarctica as a constant conveyor, carrying nutrients, plankton, and larvae around the planet’s southern girdle.

-

Migratory whales followed the seasonal sea-ice edge, feeding in austral summers and migrating north in winter.

-

Seabirds linked Antarctica to the subantarctic islands, bridging thousands of kilometers.

-

Oceanic fronts—the Polar and Subantarctic convergences—acted as invisible highways of life, defining productivity gradients that tied Antarctica to every southern ocean.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human culture existed here to interpret its grandeur, yet natural symbolism flourished:

-

The cyclic return of sunlight, the waxing and waning of ice, the rhythm of migration and reproduction—all wrote an ecological cosmology of recurrence and endurance.

-

Each year’s melt renewed the promise of life; each winter’s freeze sealed it again in blue ice and silence.

Antarctica, though empty of people, was alive with rituals of nature: nesting cycles, whale migrations, the return of krill swarms, the annual exchange of heat and light.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Life clung to margins and adapted ingeniously to extremes:

-

Microbial and algal mats developed antifreeze proteins and pigments to withstand freeze–thaw cycles.

-

Seabirds and seals synchronized breeding to brief ice-free seasons.

-

Krill populations adapted to feed beneath thinning sea ice, ensuring continuity of the entire food chain.

-

Vegetation and soil microbes colonized wind-sheltered microhabitats, enriching them over centuries.

Antarctica’s ecosystems achieved a delicate equilibrium—resilient, self-renewing, and finely tuned to the planet’s most unforgiving climate.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Antarctica had reached its Holocene form:

-

Ice sheets largely stabilized within modern bounds; ice-free oases persisted as scattered sanctuaries of life.

-

Marine productivity and migratory cycles reached full vigor, fueling the great southern food web.

-

The continent’s pristine ecosystems remained untouched, awaiting future ages when humankind would finally seek them out.

At the dawn of the Holocene, Antarctica was both a remnant of the glacial past and a promise of planetary renewal—the white mirror of Earth’s resilience, where wind, sea, and sunlight rehearsed the rhythm of life long before human memory.