Antarctica (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — …

Years: 48293BCE - 28578BCE

Antarctica (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — The Frozen Continent and Its Oceanic Halo

Geographic and Environmental Context

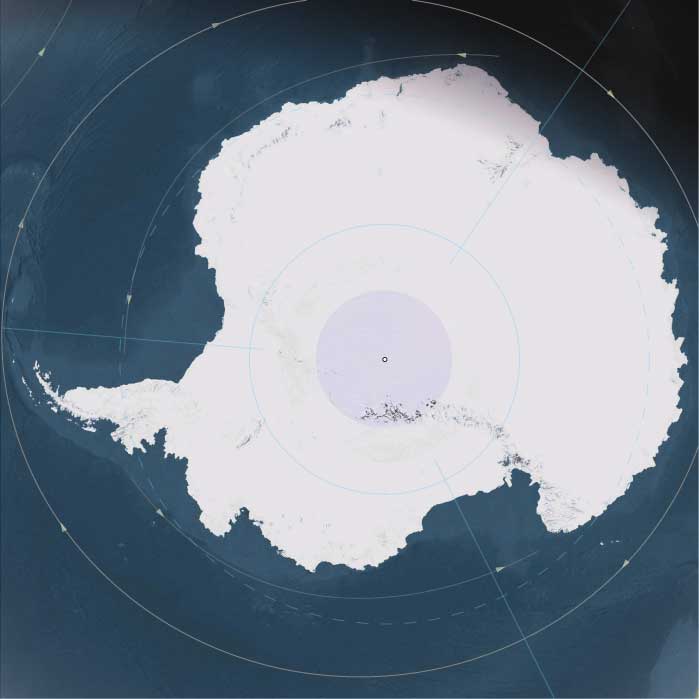

During the height of the Late Pleistocene, Antarctica stood as the coldest, driest, and most isolated world on Earth—a continent sealed in ice and girdled by the Southern Ocean.

The great landmass divided naturally into three broad realms:

-

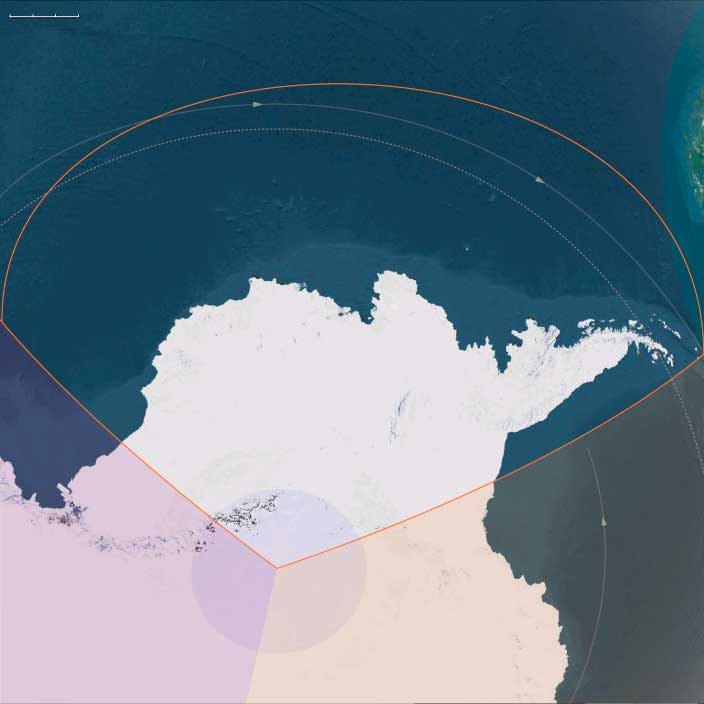

East Antarctica, the immense polar plateau rising more than 3 km above sea level, draped in ice more than 4 km thick and stretching from the Transantarctic Mountains to the Indian Ocean rim.

-

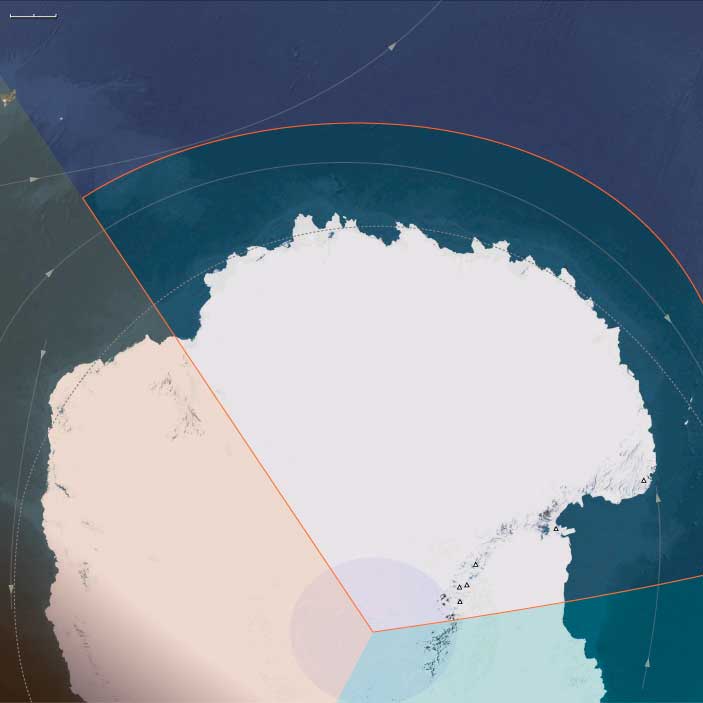

West Antarctica, a lower, fractured terrain comprising the Antarctic Peninsula, Marie Byrd Land, and the Amundsen–Ross embayments, fringed by vast floating shelves.

-

The subantarctic ring—the nearby island arcs of South Georgia, the South Orkneys, the South Sandwich Islands, Bouvet, and the Prince Edward–Marion chain—sat just beyond the continental ice but within its climatic orbit, forming Antarctica’s ecological frontier with the world’s oceans.

These divisions—polar plateau, continental rim, and subantarctic ring—behaved less like a single geography than like three interconnected systems whose unity was maintained by ice, wind, and current.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The period between 49,000 and 28,500 BCE encompassed the build-up to the Last Glacial Maximum.

-

Temperature: Mean annual values across the plateau were 10–15 °C colder than today; coastal sectors remained below freezing even in summer.

-

Ice extent: The East Antarctic Ice Sheet thickened and spread toward the coast, while the smaller West Antarctic ice masses merged, grounding on the continental shelf. Overall, Antarctica’s ice volume reached its greatest Quaternary extent.

-

Sea level: Global levels fell ~120 m, exposing continental shelves and expanding grounded ice.

-

Atmosphere: Lower greenhouse-gas concentrations and stronger katabatic winds intensified polar deserts in the interior.

-

Ocean: Sea-ice fronts advanced far north in winter, yet polynyas—open-water oases—persisted along parts of the coast, sustaining remarkable marine productivity.

The result was a planet tipped toward cold equilibrium: Antarctica at its broadest and most luminous, radiating sunlight back into space and anchoring global climate.

Flora, Fauna, and Ecology

Antarctica itself supported only microbial, algal, and cryptogamic life confined to small ice-free niches, while its surrounding seas and subantarctic islands hosted some of Earth’s richest cold-water ecosystems.

-

Terrestrial oases: Along the Dry Valleys, the Antarctic Peninsula, and scattered nunataks, thin melt-season films supported cyanobacteria, mosses, lichens, and minute invertebrates.

-

Coastal wildlife: Adélie and early emperor-penguin lineages bred on stable sea-ice platforms; skuas and petrels nested on rocky ledges.

-

Marine systems: Krill, copepods, and under-ice algae flourished beneath seasonal pack ice, feeding whales, seals, and seabirds.

-

Subantarctic ring: Islands like South Georgia and the Prince Edward group carried tussock grass, moss, and sprawling rookeries of albatrosses, petrels, and fur seals—vital nodes in the circum-polar web.

Though barren by continental standards, Antarctica’s margins were alive with motion, its biological clock synchronized to the annual advance and retreat of ice.

Human Presence and Global Context

No humans had ever set foot on this continent or its islands.

Elsewhere, Homo sapiens spread across Africa, Eurasia, and Sahul, but Antarctica lay far beyond the technological reach of any Pleistocene mariner.

Its isolation rendered it the world’s ultimate terra incognita, absent even from myth.

Yet indirectly, it mattered: the continent’s albedo, sea-ice cycles, and carbon sequestration steered the climates within which human civilizations would one day arise.

Antarctica was already humanity’s silent climate engine.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Though devoid of people, the region was a crossroads for wind, current, and life:

-

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) encircled the continent, connecting the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans into a single conveyor.

-

The westerly wind belt (“roaring forties” – “furious fifties”) drove surface circulation and upwelling that fed krill blooms.

-

Whales, seals, and seabirds migrated along these highways from every southern continent, forming a truly circum-global ecological network.

These corridors prefigured the pathways of future exploration, commerce, and science.

Symbolic and Conceptual Role

In human terms, Antarctica existed only as an absence—a mythic void beyond any known horizon.

Had Ice-Age peoples imagined it, it might have represented the under-world of ice, a place where sun and earth froze in perpetual night.

In geological reality, it was the earth’s mirror, reflecting heat and regulating balance: a physical metaphor for stasis at the edge of creation.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Antarctica’s ecosystems, though sparse, showed immense stability:

-

Glacial resilience: Microbial and moss communities endured multiple glacial advances, recolonizing from refugia during brief interstadials.

-

Marine adaptation: Krill and fish species evolved antifreeze proteins, surviving under permanent cold.

-

Carbon storage: Ice-sheet expansion sequestered atmospheric CO₂, tightening Earth’s glacial grip yet ensuring reversibility when melting resumed.

In every process—wind, ice flow, nutrient recycling—the system demonstrated the capacity of life and climate to adapt through feedback and equilibrium.

Transition Toward the Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, Antarctica had reached near-peak glacial extent.

The East Antarctic plateau remained unaltered in its frozen dominion; the West Antarctic shelves thickened; and the subantarctic islands thrived as refugia for the Southern Ocean’s living abundance.

Humanity still knew nothing of this world, yet its influence touched every other: it cooled the tropics, lowered the seas, and sculpted the very margins of habitable Earth.

In the grand pattern of The Twelve Worlds, Antarctica stood as the still point of the planet’s climatic wheel—its icy heart, unseen but omnipresent, binding the glacial age together.