Southeast Indian Ocean (49,293–28,578 BCE): Subantarctic Islands …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Southeast Indian Ocean (49,293–28,578 BCE): Subantarctic Islands in the Ice Age

Geographic & Environmental Context

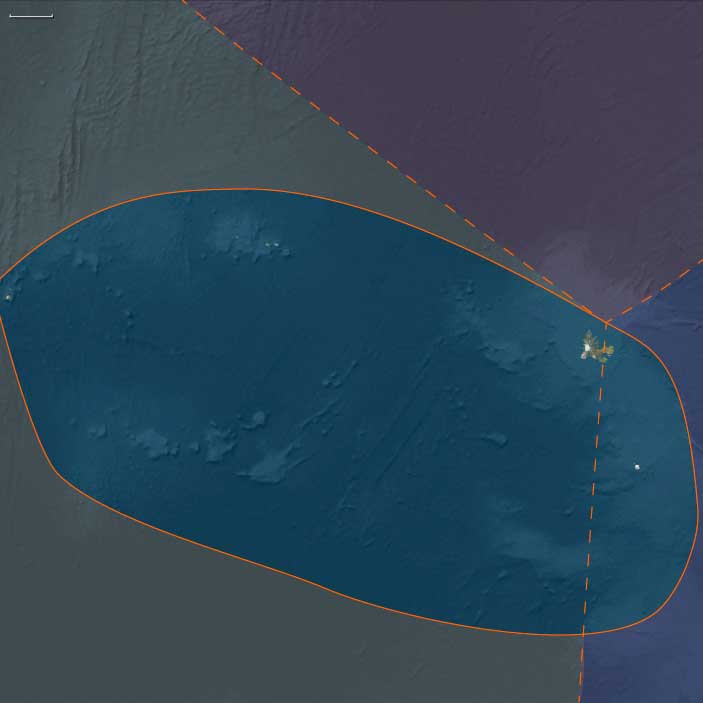

The subregion of Southeast Indian Ocean includes Kerguelen east of 70°E and Heard Island and McDonald Islands. These remote volcanic islands rise from the southern Indian Ocean far below the subtropical belt, edging into the subantarctic climatic zone. Kerguelen forms the largest landmass, with its basaltic plateaus, glacial valleys, and fjord-like inlets. Heard Island and the tiny McDonald group lie further east, dominated by the active stratovolcano Big Ben on Heard and barren rocky islets in the McDonalds. Rugged coasts, strong currents, and exposure to prevailing westerlies made these lands biologically and climatically distinct from equatorial or continental environments.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

During this Upper Paleolithic age, global sea levels were 60–90 meters lower than today, reflecting the Last Glacial Maximum’s approach. The islands’ coasts were broader, though steep cliffs and volcanic forms kept much of the shoreline dramatic. The climate was colder, windier, and drier, with glaciers expanding across Kerguelen’s uplands and icefields growing around Big Ben. Snow and ice accumulation carved valleys and extended tongues of ice to the sea. The surrounding Southern Ocean was cooler, nutrient-rich, and dynamic, sustaining upwellings that intensified productivity of marine ecosystems.

Subsistence & Settlement

No humans had yet arrived; these islands remained untouched by people until the modern era. Yet ecosystems flourished. Subantarctic tundra vegetation—mosses, lichens, cushion plants, and grasses—covered exposed surfaces. Freshwater lakes and meltwater streams hosted hardy invertebrates. The seas teemed with krill, fish, and squid, supporting colonies of seabirds and seals. Penguins likely ranged widely across the Southern Ocean during this period, using ice-free coasts for rookeries in warmer interludes. These animal communities created ecological patterns of nutrient cycling and guano fertilization that shaped the islands’ soils long before human presence.

Technology & Material Culture

Though humans had no presence here, this period corresponds globally to advances in Upper Paleolithic stone industries—blade technologies, bone tools, and art traditions in other regions. If transoceanic voyaging had improbably reached these latitudes (something for which there is no evidence), survival would have required mastery of cold-weather adaptations: sewn clothing, sea mammal hunting, and ocean-going craft. The absence of such settlement highlights the remoteness and environmental extremity of the Southeast Indian Ocean islands compared with other subantarctic or continental zones.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The islands lay within the great circumpolar circulation of winds and currents—the roaring forties and furious fifties. Oceanic systems here acted as a conveyor belt for nutrients and migrating species. Marine mammals such as seals, sea lions, and whales followed seasonal routes past Kerguelen and Heard, feeding on the plankton-rich waters. Seabirds traversed vast distances, linking the islands ecologically to Antarctica, Africa, and Australasia. Although no humans traveled these corridors at this time, the patterns they would later rely on—migratory pathways, productive fisheries—were already established.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

There were no cultural expressions tied to these islands in this age. Symbolic activity was flourishing elsewhere: cave paintings in Europe, ritual burials in Asia, and ornaments in Africa. If known, such remote islands might have carried a liminal symbolic weight as places beyond the margins of human habitation. But in this period, they remained outside the human imaginative sphere.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Ecosystems on Kerguelen and Heard demonstrated resilience to glacial fluctuations. Plant life endured in sheltered microclimates, retreating and re-expanding as glaciers advanced and retreated. Bird and seal populations adapted to shifting ice fronts, relocating rookeries and haul-out sites. The islands thus exemplified how subantarctic ecologies reorganize under climatic stress, laying groundwork for the resilience patterns observed into the Holocene.

Transition

By 28,578 BCE, the glacial maximum was approaching, with ice sheets at their most extensive. The Southeast Indian Ocean islands stood as icy outposts, ecologically vibrant but humanly unvisited. Their landscapes were already etched by glaciers, storms, and ocean swells—patterns that would persist until humans finally encountered them millennia later.