Atlantic Southwest Europe (820 – 963 CE): …

Years: 820 - 963

Atlantic Southwest Europe (820 – 963 CE): Asturias–León Frontiers, Portucale Marches, and the Atlantic Pilgrim Sea

Geographic and Environmental Context

Atlantic Southwest Europe includes northern Spain and central to northern Portugal, including Lisbon.

-

Core landscapes: the Cantabrian and Galician coasts, the Minho–Douro and upper Mondego basins, the Asturian and Galician ranges, and the inland plateaus feeding the Duero.

-

Urban nodes and strongholds: Oviedo, León, Burgos (founded 884), Porto (reoccupied 868), Braga, Coimbra (taken 878; frontier thereafter), and Lisbon (an al-Andalus port within the subregion’s southern rim).

-

The Bay of Biscay and Atlantic river mouths tied interior cereals and stock to maritime routes toward Aquitaine, Brittany, and the English Channel.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

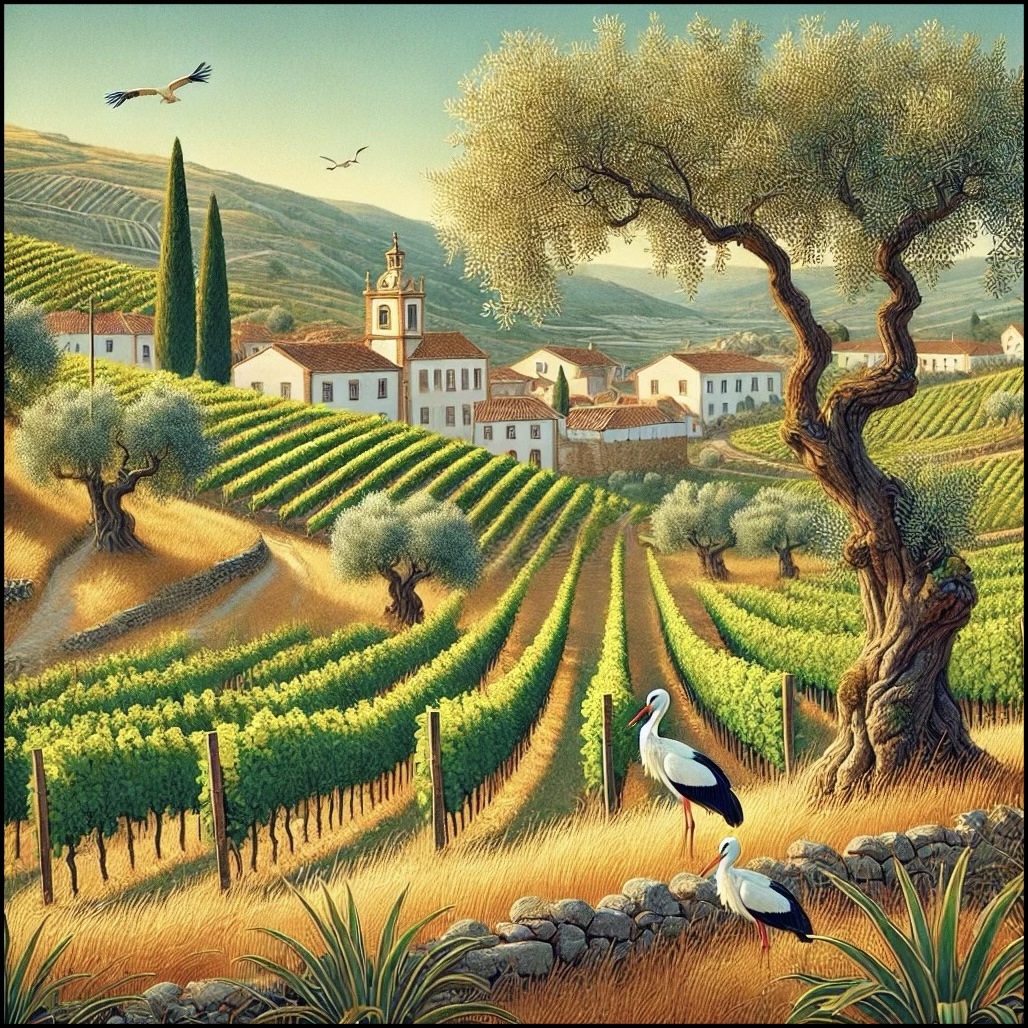

A cool–temperate maritime regime with high rainfall along the Cantabrian–Galician arc supported oak–chestnut woodlands, pastures, and vines.

-

Toward the mid-10th century, the onset of the Medieval Warm Period modestly lengthened growing seasons, aiding vineyards on sunny slopes and transhumant meadows inland.

-

River floods on the Minho and Douro enriched lowland fields but dictated transport calendars.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Asturias → León: Under Alfonso II (791–842), Ramiro I (842–850), Ordoño I (850–866), and Alfonso III (866–910), the Asturian monarchy expanded east and south, founding and refortifying castillos along the Duero. In 910, the court shifted to León, inaugurating the Kingdom of León.

-

Piaculine Marches & Castile: The County of Castile coalesced on the eastern Duero marches; by the 930s–950s Fernán González consolidated comital autonomy, anchoring new fort lines from Burgos into the upper Ebro.

-

Galicia: Integrated within León, with powerful monasteries and magnates shaping the Atlantic façade.

-

Kingdom of Pamplona (Navarre) and the County of Barcelona (just beyond the subregion) influenced cross-Pyrenean diplomacy and trade that reached these Atlantic provinces.

-

Portucale (County of Porto): Vímara Peres reoccupied Porto (868), initiating repopulation (repoblación) between Minho–Douro; Coimbra fell to León (878), then remained a vulnerable march.

-

Lisbon: Within our geographic frame but under Umayyad (and after 929, Córdoban caliphal) rule—an Islamic entrepôt facing the Tagus estuary and Atlantic lanes.

Economy and Trade

-

Agrarian base: rye, wheat, barley, and millets on the plateaus; vineyards on south-facing terraces; chestnut and oak mast feeding swine; dairying in Atlantic hills.

-

Stock & salt: coastal saltworks (Aveiro, Vigo rías) and river fisheries provisioned towns and monasteries; wool and hides moved inland–coast.

-

Maritime exchange: cabotage from Gijón, A Coruña, Porto, and the Tagus linked to Bordeaux, Bayonne, Nantes, and Rouen; Lisbon’s Andalusi merchants connected Atlantic traffic to Córdoba and Seville.

-

Pilgrim economy: after the discovery of St. James’ relics at Compostela (c. 820, in Alfonso II’s time), a nascent Camino network drew pilgrims, alms, and artisans across the Pyrenees, stimulating markets from Oviedo to Santiago.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Heavy plow and ard mixed use: heavier soils of the Duero loess took the carruca where teams and seigneurial fields existed; lighter tools persisted in hill farms.

-

Water-mills multiplied on Atlantic streams; terracing and dry-stone retaining walls expanded vine and horti-culture.

-

Shipcraft: clinker-built coasters and river barges served bays and estuaries; riverine craft moved grain and timber down the Minho and Douro.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Cantabrian coastal road (the later Camino del Norte) and emerging Camino spurs toward Santiago de Compostela funneled people and goods.

-

Duero line of fortresses and bridge-fords structured inland resettlement and tolling.

-

Atlantic lanes linked Porto–Lisbon with Aquitaine and Brittany; overland links ran through Astorga–León–Burgos toward the Ebro and Pyrenees.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Latin Christianity structured kingship and repopulation: churches and monasteries (e.g., Celanova, Samos) endowed with lands and tolls; charters (cartas pueblas) framed settlement rights.

-

The cult of Santiago transformed Galicia into a pan-European sacred destination; reliquaries, way-crosses, and hospitalia marked routes.

-

In Lisbon and Islamic marches: mosques, qāḍī courts, and Arabic chancery served Andalusi authority; Mozarab Christians preserved Latin rite under Islamic law.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Frontier layering—fortified ridges, river crossings, and monastic estates—absorbed raids and stabilized repopulation.

-

Mixed agro-pastoral portfolios (grain + vines + chestnut + stock + fisheries) buffered climate variability.

-

Route redundancy (coastal Camino, interior Duero tracks, sea lanes) kept exchange flowing despite warfare.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, Atlantic Southwest Europe had become a two-frontier commonwealth:

-

A Christian Asturias–León heartland pushing fort lines to the Duero with Castile and Portucale as dynamic marches, energized by the Compostela cult;

-

An Andalusi Lisbon–Tagus outpost knitting the Atlantic to Córdoba.

These institutions—marcher lordship, monastic landholding, and Atlantic pilgrimage/trade—forged the economic and sacred geographies that would power the great expansions of the later 10th–11th centuries.

Atlantic Southwest Europe (with civilization) ©2024-26 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

People

- Alfonso II of Asturias

- Alfonso III of Asturias

- Fernán González

- Ordoño I of Asturias

- Ramiro I of Asturias

- Vímara Peres

Groups

- Galicia, Kingdom of

- Christianity, Chalcedonian

- Muslims, Sunni

- Mozarabs

- Portuguese people

- Navarre, Kingdom of

- Asturias, Kingdom of

- Portugal, (first) County of

- León, Kingdom of

- Córdoba, (Umayyad) Caliphate of

Topics

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Fibers

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Beer, wine, and spirits

- Manufactured goods

Subjects

- Commerce

- Architecture

- Watercraft

- Painting and Drawing

- Labor and Service

- Conflict

- Faith

- Government

- Technology

- Metallurgy