Albrecht Altdorfer, born probably in Regensburg, had …

Years: 1511 - 1511

Albrecht Altdorfer, born probably in Regensburg, had become a citizen there in 1505 at the age of twenty-five.

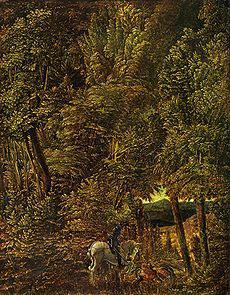

He paints in 1510 a small St. George and the Dragon in oil on parchment, where the saint and the dragon are small figures almost submerged in the dense forest that towers over them.

He makes a trip down the Danube in 1511 to work in Vienna.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 39308 total

A Portuguese fleet commanded by viceroy Afonso de Albuquerque, carrying more than a thousand men in eighteen ships, including Ferdinand Magellan and Francisco Serrão, captures the powerful Muslim Malay state of Malacca two years after the rebuffal by its sultan, thereby gaining control of the Strait of Malacca.

Albuquerque builds a naval base here.

The sultan of Demak launches a counterattack in 1511 against the encroaching Portuguese merchant-warriors, who repulse the attempt.

Ayutthaya, having subdued Sukhothai and other small kingdoms in the latter half of the fourteenth century, has become a regional center of wealth and power.

Ayutthayan King Ramathibodi II had in 1500 sent the Siamese armies to subjugate the Sultanate of Malacca.

Though unable to conquer Malacca, Siam had managed to exact tributes from the Malacca sultanate and other sultanates like Pattani, Pahang, and Kelantan.

After the Portuguese, under Viceroy Alfonso d’Albuquerque, capture Malacca in 1511, Albuquerque, knowing of Siamese ambitions towards the Malay lands, sends Duarte Fernandez on a diplomatic mission to Ayutthaya, which claims rights over Malacca.

Fernandez, a tailor, had gone to Malacca in the first expedition of Diogo Lopes de Sequeira in September 1509.

In the sequence of a failed plot to destroy the expedition, Fernandez had been among nineteen Portuguese who stood arrested in Malacca, together with Rui de Araújo, having gathered knowledge about the culture of the region.

Traveling in a Chinese junk returning home, Fernandez is the first European to arrive here, establishing amicable relations between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Kingdom of Siam, returning with a Siamese envoy with gifts and letters to Albuquerque and the king of Portugal.

Makassar has by the sixteenth century become Sulawesi's major port and center of the powerful Gowa and Tallo sultanates, which between them have a series of eleven fortresses and strongholds and a fortified sea wall that extends along the coast.

Portuguese rulers call the city Macáçar.

Having become the dominant trading center of eastern Indonesia, Makassar will soon become one of the largest cities in island Southeast Asia.

The Makassar kings maintain a policy of free trade, insisting on the right of any visitor to do business in the city, and will reject the later attempts of the Dutch to establish a monopoly over the city in the early seventeenth century.

The trade in spices figures prominently in the history of Sulawesi, which involves frequent struggles between rival native and foreign powers for control of the lucrative trade during the pre-colonial and colonial period, when spices from the region are in high demand in the West.

Much of South Sulawesi's early history is written in old texts that can be traced back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

Further, tolerant religious attitudes mean that even as Islam becomes the dominant faith in the region, Christians and others are still able to trade in the city.

With these attractions, Makassar is a key center for Malays working in the spice trade, as well as a valuable base for European and Arab traders from much further afield.

The first European settlers are the Portuguese sailors.

When the Portuguese reach Sulawesi in 1511, they find Makassar a thriving cosmopolitan entrepôt where Chinese, Arabs, Indians, Siamese, Javanese, and Malays come to trade their manufactured metal goods and textiles for pearls, gold, copper, camphor and spices—nutmeg, cloves and mace imported from the interior and the neighboring Spice Islands of Maluku.

Hans von Kulmbach’s talents as an outstanding colorist and a gifted and sensitive portraitist are apparent in his Margrave Casimir of Hohenzollern, painted in 1511.

Hans Holbein the Elder, sometimes assisted by his brother Sigmund, also a painter, continues to train his sons, Hans the Younger and Ambrosius, and paint in his large Augsburg studio.

Selim I is described as being tall, having very broad shoulders and a long mustache.

He is skilled in politics and is said to be fond of fighting.

In 1494, at Trabzon, he had married Ayşe Hafsa Sultan, the daughter of Meñli I Giray.

Although Selim's son Süleyman had been assigned to Bolu, a small sanjak closer to Istanbul, upon Ahmet's objection, he had been relocated to Caffe in Crimea.

Selim, seeing this as an unofficial display of support for his older brother, had asked for a sanjak in Rumeli (the European portion of the empire).

Although he had initially refused on the ground that Rumeli sanjaks are not offered to princes, with the support of the vassal Crimean khan Meñli I Giray (who was his father-in-law), he has been able to receive the sanjak of Semendire (modern Smederevo in Serbia), which, although it is technically in Rumeli, is quite far from Istanbul nevertheless.

Consequently, Selim chooses to stay close to Istanbul instead of going to his new sanjak.

His father Bayezid thinks this disobedience insurrectionist; he defeats Selim's forces in battle in August 1511, and Selim escapes to the Crimea.

Bayezid II develops fears that Ahmet might in turn kill him to gain the throne and refuses to allow his son to enter Constantinople.

His grand vizier is absent, fighting the rebellion of the Shi'ite Turkmen followers of Shah Ismail, when bayezid surprised by his son and designated successor, Ahmed, who calls for his father’s abdication.

A threatened revolt by the Janissaries against Ahmed fails to materialize only by Bayezid’s refusal to abdicate.

Ahmed and his brother Kortud now attempt to gain power in Anatolia.

Ahmet declares himself as the sultan of Anatolia afterhearing about Selim's defeat by their father, and begins fighting against one of his nephews (whose father had already been killed).

He captures Konya, and although his father Bayazid asks him to return to his sanjak, he insists on ruling in Konya.

He also attempts to capture the capital; but he fails because the soldiers block his way, declaring their preference for a more able sultan.

Şahkulu is thought by his partisans to be invincible after he raids a royal caravan and kills a high-ranking Ottoman statesman.

A second army is sent after him, commanded by Şehzade Ahmet, one of the claimants to throne, and the grand vizier Hadım Ali Pasha.

They are able to corner Şahkulu near Altıntaş (in modern Kütahya Province), but instead of fighting, Ahmet tried to win over the Janissaries to his cause.

Failing to achieve this, he leaves the battlefield.

Şahkulu sees his chance and escapes.

Ali Pasha, with a smaller force, chases him and clashes with him at Çubukova between Kayseri and Sivas.

The battle, which takes place in July 1511, is a draw, but both Ali Pasha and Şahkulu are killed (July 1511).

However, the conditions that have caused the uprising will remain a major problem for Bayezid's successor.

Şahkulu's partisans are not defeated, but they have lost their leader.

Many scatter, but after a third army is sent by the Ottoman Porte, the most devoted escape to Persia.

During their escape they raid a caravan, and accidentally kill a well-known Persian scholar.

Consequently, instead of showing them hospitality, Ismail executes them.

Meanwhile, in Ottoman lands, Prince Ahmet's behavior in the battle caused reaction among the soldiers.

Moreover the death of Hadım Ali, the chief partisan of Ahmet, provides an advantage to the youngest claimants to throne: the succession will ultimately fall to Selim I, under whose reign the Ottoman state will see spectacular victories and double in area.