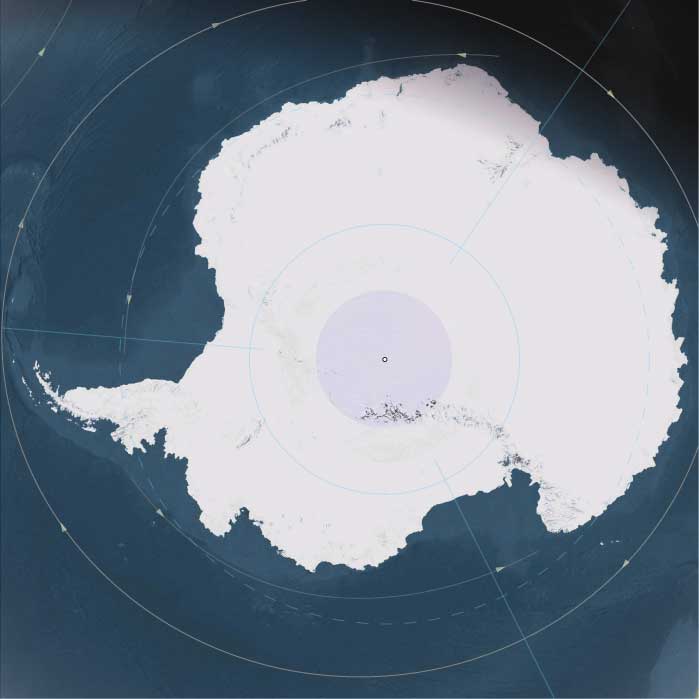

West Antarctica (2637 – 910 BCE): Fragmented …

Years: 2637BCE - 910BCE

West Antarctica (2637 – 910 BCE): Fragmented Ice Lands and Coastal Wildlife Havens

Geographic and Environmental Context

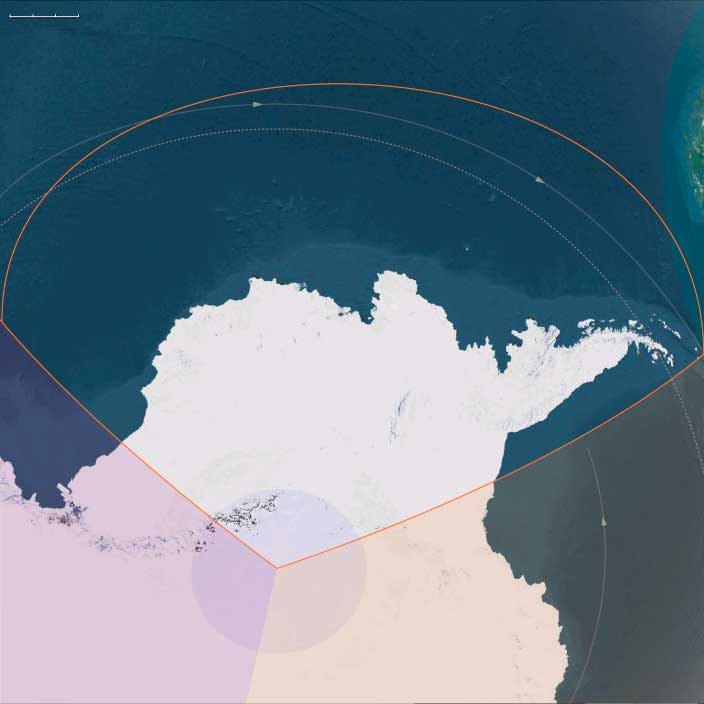

West Antarctica—including the Antarctic Peninsula, the Amundsen Sea and Bellingshausen Sea sectors, the scattered coastal ice shelves of Marie Byrd Land, and Peter I Island—was geologically distinct from East Antarctica. Instead of a single massive plateau, it consisted of smaller, lower-elevation ice domes separated by deep marine basins. Much of its bedrock lay below sea level, making it vulnerable to ice retreat during warmer intervals.

Peter I Island, a small volcanic landmass in the Bellingshausen Sea about 450 km off the Antarctic coast, rose from the Southern Ocean as an ice-clad, sheer-sided fortress of rock and glacier. Like the Antarctic Peninsula, it represented one of the few places in West Antarctica where rocky terrain broke through the ice sheet.

Climate and Environmental Conditions

The Antarctic Peninsula had the mildest climate on the mainland, with summer temperatures occasionally reaching above freezing in sheltered coastal sites. The surrounding seas experienced seasonal sea ice retreat, creating biologically rich ice edges and open-water areas (polynyas). Farther south, the Amundsen and Bellingshausen coasts remained locked in heavier pack ice for much of the year.

Peter I Island, isolated and surrounded by pack ice, endured similar conditions to the Bellingshausen coast—persistent cold, high winds, and short summer thaws exposing limited ice-free ground.

Biological Productivity

Although inhospitable to terrestrial vegetation beyond mosses and lichens, the West Antarctic coasts and nearby islands supported intense summer bursts of life:

-

Penguins – Adélie and gentoo colonies nested on ice-free slopes of the Antarctic Peninsula and surrounding islands.

-

Seals – Weddell, crabeater, and leopard seals hauled out on sea ice and beaches.

-

Seabirds – Petrels, skuas, and sheathbills foraged widely, with some nesting on rocky headlands.

Peter I Island, though small, provided seasonal rookeries for seabirds and occasional haul-out spots for seals.

Human Presence

During 2637 – 910 BCE, West Antarctica, including Peter I Island, was completely beyond human reach. The region’s remoteness from inhabited lands, the barrier of the Drake Passage, and the formidable pack ice made access impossible for the maritime technology of the time. Even the closest human populations in southern South America and the subantarctic islands could not approach or survive in these polar conditions.

Symbolic and Conceptual Absence

These lands lay outside the mental maps of all ancient peoples, existing only as an unseen and unimagined realm. If the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula was ever glimpsed from distant southern waters, it would have appeared as a remote, cloud-shrouded mountain range with no obvious signs of life or landfall.

Environmental Adaptation of Local Life

Wildlife here was adapted to the extreme cold and seasonal food booms: penguins bred during the short summer to raise chicks before the onset of winter darkness, seals synchronized pupping with peak prey availability, and seabirds timed migrations to match the productivity of Antarctic waters.

Transition to the Early First Millennium BCE

By 910 BCE, West Antarctica remained a frozen and isolated domain, unvisited by humans but vital to marine ecosystems. Its scattered rocky outcrops—like Peter I Island—and productive summer coastlines were important ecological nodes in the Southern Ocean, long before human exploration reached these latitudes.

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 68553 total

We begin in the easternmost subregions and move westwardly around the globe, crossing the equator as many as six times to explore ever shorter time periods as we continue to circle the planet. The maps of the regions and subregions change to reflect the appropriate time period.

Narrow results by searching for a word or selecting from one or more of a dozen filters.

Its origins seem to be in the Lena river basin of Yakutia, and also along the Yenisei river; individual sites will also be found in Taymyr.

From there it spreads both to the east and to the west.

Northern West Indies (2637 – 910 BCE): Island Arcs of the Atlantic Gateway

Geographic and Environmental Context

The Northern West Indies—including Bermuda, the Turks and Caicos Islands, and the northern portion of Hispaniola (including Santiago de los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic and Cap-Haïtien in Haiti)—lay along the boundary between the open Atlantic and the sheltered Caribbean. This arc of islands combined low-lying coral platforms (Bermuda, Turks and Caicos) with the mountainous, fertile uplands of northern Hispaniola. Warm waters of the Gulf Stream influenced the northern islands, while Caribbean currents bathed the southern edge of the subregion.

Subsistence and Settlement

By the mid–third millennium BCE, permanent human settlement in the Northern West Indies was unlikely, especially on Bermuda and the Turks and Caicos, but these islands may have been within the range of exploratory or seasonal voyaging by early maritime cultures from the Greater Antilles or the Florida–Bahamas–Cuba corridor.

Hispaniola’s northern coast, however, offered fertile valleys, river floodplains, and abundant marine resources. Here, early Indigenous communities likely practiced mixed economies: fishing, shellfish gathering, hunting small game, and cultivating or managing root crops and fruits in tropical forest clearings.

Technological and Cultural Developments

Maritime technology included dugout canoes carved from large hardwood logs, enabling short- and medium-range coastal travel and inter-island movement in the calmer seasons. Fishing gear included bone and shell hooks, woven traps, and spears. Stone adzes, grinding stones, and hammerstones were used for woodworking, food preparation, and shell ornament production.

In northern Hispaniola, early ceramic traditions may have been emerging toward the end of this epoch, influenced by contacts with other Antillean and circum-Caribbean cultures.

Maritime and Trade Networks

Although Bermuda’s distance from continental shores would have made it a challenging target for early voyagers, the Turks and Caicos lay within plausible canoe range of the Bahamas and Hispaniola. Inter-island exchange in this era would likely have been limited to high-value portable goods—shell beads, stone tools, and possibly dried fish. Hispaniola’s coastal settlements were well-positioned to engage in maritime foraging and short-distance trade with neighboring islands.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

In northern Hispaniola, coastal and riverine sites may have included shell midden deposits serving both as refuse and as territorial markers. Ornamentation with shell, coral, and stone beads reflected personal and group identity. Ritual practices—later preserved in descendant traditions—likely tied seasonal fishing abundance and land fertility to spiritual forces associated with the sea and sky.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Island communities relied on diversified subsistence strategies, combining marine and terrestrial foods to buffer against seasonal shortages or storm impacts. Knowledge of seasonal wind and current patterns was essential for safe canoe travel. On smaller coral islands, freshwater scarcity would have required careful rainwater collection and reliance on imported goods from larger landmasses.

Transition to the Early First Millennium BCE

By 910 BCE, the Northern West Indies likely remained lightly used and sparsely inhabited, but its fertile coasts, rich fishing grounds, and strategic position made it an important ecological and navigational zone. In the centuries ahead, it would become more deeply integrated into the wider web of Caribbean maritime networks.

Northern West Indies (2637 – 910 BCE): Island Arcs of the Atlantic Gateway

Geographic and Environmental Context

The Northern West Indies—including Bermuda, the Turks and Caicos Islands, and the northern portion of Hispaniola (including Santiago de los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic and Cap-Haïtien in Haiti)—lay along the boundary between the open Atlantic and the sheltered Caribbean. This arc of islands combined low-lying coral platforms (Bermuda, Turks and Caicos) with the mountainous, fertile uplands of northern Hispaniola. Warm waters of the Gulf Stream influenced the northern islands, while Caribbean currents bathed the southern edge of the subregion.

Subsistence and Settlement

By the mid–third millennium BCE, permanent human settlement in the Northern West Indies was unlikely, especially on Bermuda and the Turks and Caicos, but these islands may have been within the range of exploratory or seasonal voyaging by early maritime cultures from the Greater Antilles or the Florida–Bahamas–Cuba corridor.

Hispaniola’s northern coast, however, offered fertile valleys, river floodplains, and abundant marine resources. Here, early Indigenous communities likely practiced mixed economies: fishing, shellfish gathering, hunting small game, and cultivating or managing root crops and fruits in tropical forest clearings.

Technological and Cultural Developments

Maritime technology included dugout canoes carved from large hardwood logs, enabling short- and medium-range coastal travel and inter-island movement in the calmer seasons. Fishing gear included bone and shell hooks, woven traps, and spears. Stone adzes, grinding stones, and hammerstones were used for woodworking, food preparation, and shell ornament production.

In northern Hispaniola, early ceramic traditions may have been emerging toward the end of this epoch, influenced by contacts with other Antillean and circum-Caribbean cultures.

Maritime and Trade Networks

Although Bermuda’s distance from continental shores would have made it a challenging target for early voyagers, the Turks and Caicos lay within plausible canoe range of the Bahamas and Hispaniola. Inter-island exchange in this era would likely have been limited to high-value portable goods—shell beads, stone tools, and possibly dried fish. Hispaniola’s coastal settlements were well-positioned to engage in maritime foraging and short-distance trade with neighboring islands.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

In northern Hispaniola, coastal and riverine sites may have included shell midden deposits serving both as refuse and as territorial markers. Ornamentation with shell, coral, and stone beads reflected personal and group identity. Ritual practices—later preserved in descendant traditions—likely tied seasonal fishing abundance and land fertility to spiritual forces associated with the sea and sky.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Island communities relied on diversified subsistence strategies, combining marine and terrestrial foods to buffer against seasonal shortages or storm impacts. Knowledge of seasonal wind and current patterns was essential for safe canoe travel. On smaller coral islands, freshwater scarcity would have required careful rainwater collection and reliance on imported goods from larger landmasses.

Transition to the Early First Millennium BCE

By 910 BCE, the Northern West Indies likely remained lightly used and sparsely inhabited, but its fertile coasts, rich fishing grounds, and strategic position made it an important ecological and navigational zone. In the centuries ahead, it would become more deeply integrated into the wider web of Caribbean maritime networks.

Northern West Indies (2637 – 910 BCE): Island Arcs of the Atlantic Gateway

Geographic and Environmental Context

The Northern West Indies—including Bermuda, the Turks and Caicos Islands, and the northern portion of Hispaniola (including Santiago de los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic and Cap-Haïtien in Haiti)—lay along the boundary between the open Atlantic and the sheltered Caribbean. This arc of islands combined low-lying coral platforms (Bermuda, Turks and Caicos) with the mountainous, fertile uplands of northern Hispaniola. Warm waters of the Gulf Stream influenced the northern islands, while Caribbean currents bathed the southern edge of the subregion.

Subsistence and Settlement

By the mid–third millennium BCE, permanent human settlement in the Northern West Indies was unlikely, especially on Bermuda and the Turks and Caicos, but these islands may have been within the range of exploratory or seasonal voyaging by early maritime cultures from the Greater Antilles or the Florida–Bahamas–Cuba corridor.

Hispaniola’s northern coast, however, offered fertile valleys, river floodplains, and abundant marine resources. Here, early Indigenous communities likely practiced mixed economies: fishing, shellfish gathering, hunting small game, and cultivating or managing root crops and fruits in tropical forest clearings.

Technological and Cultural Developments

Maritime technology included dugout canoes carved from large hardwood logs, enabling short- and medium-range coastal travel and inter-island movement in the calmer seasons. Fishing gear included bone and shell hooks, woven traps, and spears. Stone adzes, grinding stones, and hammerstones were used for woodworking, food preparation, and shell ornament production.

In northern Hispaniola, early ceramic traditions may have been emerging toward the end of this epoch, influenced by contacts with other Antillean and circum-Caribbean cultures.

Maritime and Trade Networks

Although Bermuda’s distance from continental shores would have made it a challenging target for early voyagers, the Turks and Caicos lay within plausible canoe range of the Bahamas and Hispaniola. Inter-island exchange in this era would likely have been limited to high-value portable goods—shell beads, stone tools, and possibly dried fish. Hispaniola’s coastal settlements were well-positioned to engage in maritime foraging and short-distance trade with neighboring islands.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

In northern Hispaniola, coastal and riverine sites may have included shell midden deposits serving both as refuse and as territorial markers. Ornamentation with shell, coral, and stone beads reflected personal and group identity. Ritual practices—later preserved in descendant traditions—likely tied seasonal fishing abundance and land fertility to spiritual forces associated with the sea and sky.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Island communities relied on diversified subsistence strategies, combining marine and terrestrial foods to buffer against seasonal shortages or storm impacts. Knowledge of seasonal wind and current patterns was essential for safe canoe travel. On smaller coral islands, freshwater scarcity would have required careful rainwater collection and reliance on imported goods from larger landmasses.

Transition to the Early First Millennium BCE

By 910 BCE, the Northern West Indies likely remained lightly used and sparsely inhabited, but its fertile coasts, rich fishing grounds, and strategic position made it an important ecological and navigational zone. In the centuries ahead, it would become more deeply integrated into the wider web of Caribbean maritime networks.

Northern West Indies (2637 – 910 BCE): Island Arcs of the Atlantic Gateway

Geographic and Environmental Context

The Northern West Indies—including Bermuda, the Turks and Caicos Islands, and the northern portion of Hispaniola (including Santiago de los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic and Cap-Haïtien in Haiti)—lay along the boundary between the open Atlantic and the sheltered Caribbean. This arc of islands combined low-lying coral platforms (Bermuda, Turks and Caicos) with the mountainous, fertile uplands of northern Hispaniola. Warm waters of the Gulf Stream influenced the northern islands, while Caribbean currents bathed the southern edge of the subregion.

Subsistence and Settlement

By the mid–third millennium BCE, permanent human settlement in the Northern West Indies was unlikely, especially on Bermuda and the Turks and Caicos, but these islands may have been within the range of exploratory or seasonal voyaging by early maritime cultures from the Greater Antilles or the Florida–Bahamas–Cuba corridor.

Hispaniola’s northern coast, however, offered fertile valleys, river floodplains, and abundant marine resources. Here, early Indigenous communities likely practiced mixed economies: fishing, shellfish gathering, hunting small game, and cultivating or managing root crops and fruits in tropical forest clearings.

Technological and Cultural Developments

Maritime technology included dugout canoes carved from large hardwood logs, enabling short- and medium-range coastal travel and inter-island movement in the calmer seasons. Fishing gear included bone and shell hooks, woven traps, and spears. Stone adzes, grinding stones, and hammerstones were used for woodworking, food preparation, and shell ornament production.

In northern Hispaniola, early ceramic traditions may have been emerging toward the end of this epoch, influenced by contacts with other Antillean and circum-Caribbean cultures.

Maritime and Trade Networks

Although Bermuda’s distance from continental shores would have made it a challenging target for early voyagers, the Turks and Caicos lay within plausible canoe range of the Bahamas and Hispaniola. Inter-island exchange in this era would likely have been limited to high-value portable goods—shell beads, stone tools, and possibly dried fish. Hispaniola’s coastal settlements were well-positioned to engage in maritime foraging and short-distance trade with neighboring islands.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

In northern Hispaniola, coastal and riverine sites may have included shell midden deposits serving both as refuse and as territorial markers. Ornamentation with shell, coral, and stone beads reflected personal and group identity. Ritual practices—later preserved in descendant traditions—likely tied seasonal fishing abundance and land fertility to spiritual forces associated with the sea and sky.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Island communities relied on diversified subsistence strategies, combining marine and terrestrial foods to buffer against seasonal shortages or storm impacts. Knowledge of seasonal wind and current patterns was essential for safe canoe travel. On smaller coral islands, freshwater scarcity would have required careful rainwater collection and reliance on imported goods from larger landmasses.

Transition to the Early First Millennium BCE

By 910 BCE, the Northern West Indies likely remained lightly used and sparsely inhabited, but its fertile coasts, rich fishing grounds, and strategic position made it an important ecological and navigational zone. In the centuries ahead, it would become more deeply integrated into the wider web of Caribbean maritime networks.

Northeastern Eurasia (2637 – 910 BCE): Bronze and Early Iron — Steppe, Forest, and Sea Corridors of the North

Regional Overview

Stretching from the Carpathian steppes to the Amur River and Okhotsk coast, Northeastern Eurasia formed one of the great connective tissues of the ancient world.

It was a realm where bronze, horses, and furs flowed between the Eurasian heartlands and the Pacific Rim.

Across its vastness, riverine farming villages, pastoral nomads, and maritime foragers forged adaptive systems that endured millennia of climatic and cultural change.

Geography and Environment

Northeastern Eurasia comprised three immense cultural landscapes:

-

the steppe–forest–river corridor of East Europe,

-

the mountain–basin–taiga arc of Northwest Asia, and

-

the riverine–maritime frontier of Northeast Asia.

From the Black and Caspian seas to the Pacific, the region spanned temperate forests, arid grasslands, and subarctic coasts.

Major waterways—the Dniester, Volga, Ob, Yenisei, and Amur—served as continental highways, uniting inland producers with distant trade spheres.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

After 2600 BCE, gradual cooling tempered the mid-Holocene warmth.

Aridity cycles reshaped steppe ecology, encouraging mobility, while northern forests and salmon rivers remained stable.

Periodic droughts on the southern plains were balanced by resource-rich rivers and coasts farther north, allowing the region to function as an interconnected ecological mosaic.

Societies and Political Developments

East Europe – Forest–Steppe Gateways

Here, mixed farmers and herders shared the landscape with mobile steppe nomads.

The Catacomb and later Srubnaya cultures built kurgan mounds and timbered graves, developing chariotry and equestrian prestige.

Northern forest peoples pursued hunting, trapping, and fishing while trading furs and amber downriver.

The great river valleys—Dnieper, Don, and Volga—became arteries of a transcontinental economy linking the Baltic, Black Sea, and Caspian worlds.

Northwest Asia – Steppe Nomads and Metallurgists

The Andronovo and Karasuk cultures of the Altai–Yenisei region perfected pastoral nomadism and bronze metallurgy.

Horse herding, dairy use, and wheeled vehicles expanded mobility across Western Siberia’s open plains.

Petroglyphs of riders, chariots, and solar emblems testify to a cosmology centered on the sun, sky, and movement.

Taiga foragers and herders exchanged furs and fish for metals, linking steppe caravans with Arctic rivers.

Northeast Asia – River Chiefs and Maritime Foragers

Along the Amur–Ussuri system and Okhotsk coast, salmon-based chiefdoms controlled fisheries and trade in furs, oils, and metals.

Small quantities of bronze and iron filtered in via Manchuria and Korea, while local economies remained rooted in fishing, hunting, and limited horticulture.

On Hokkaidō, Epi-Jōmon cultures maintained complex foraging traditions, blending marine resources with emerging agricultural knowledge.

By the end of the period, lineages of riverine leaders managed alliances and ceremonial feasts, precursors to the Okhotsk and Satsumon societies.

Economy and Technology

-

Agriculture and Herding: Mixed grain cultivation and livestock herding characterized steppe and forest-steppe zones; pastoral nomads relied on horses, cattle, and sheep, while northern groups emphasized fish, game, and reindeer.

-

Metallurgy: Bronze dominated the toolkit—axes, daggers, ornaments; iron appeared only near the close of the epoch.

-

Mobility: Wagons, chariots, skin boats, and sledges made this one of the most mobile regions of the ancient world.

-

Trade: Amber, furs, wool, horses, and metals crossed from Europe to Asia; tin and jade moved westward; long rivers bound inland communities to coastal trade.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

Across Northeastern Eurasia, ritual landscapes reflected a shared reverence for ancestors, animals, and the sun.

-

Steppe kurgans enshrined warriors and chieftains beneath earthen mounds.

-

Taiga and Amur villages offered fish, weapons, and carved idols in riverbanks and wetlands.

-

Rock art portrayed hunters, charioteers, solar disks, and ships, blending ecological observation with spiritual cosmology.

-

Feasting and gift exchange affirmed alliances across the vast ecological frontier.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Mobility was the key to survival.

Nomads tracked pastures; fishermen followed salmon runs; foragers shifted with game migrations.

Diversified economies—grain, herds, fish, and furs—buffered communities against drought or freeze.

Storage pits, smoked fish, and dried meat ensured winter security, while interregional exchange redistributed surpluses.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 910 BCE, Northeastern Eurasia was a continent-spanning web of pastoral, agrarian, and maritime societies.

Its steppe corridors funneled innovations—horse riding, chariots, metallurgy—between Europe and East Asia.

Its riverine and coastal frontiers sustained rich fisheries and trade nodes that would feed into later Silk Road systems.

The fusion of mobility, metallurgy, and environmental adaptability forged one of humanity’s most enduring cultural ecologies—a dynamic northern realm bridging the forests of Europe, the deserts of Central Asia, and the seas of the Pacific Rim.

Northeast Asia (2,637 – 910 BCE): Metal Frontiers, River Chiefs, and Epi-Jōmon Persistence

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northeast Asia includes eastern Siberia east of the Lena River to the Pacific, the Russian Far East (excluding the southern Primorsky/Vladivostok corner), northern Hokkaidō (above its southwestern peninsula), and extreme northeastern Heilongjiang.

-

Anchors: Lower Amur chiefdom nodes, Ussuri tributaries, Sakhalin north–south corridor, Okhotsk shore villages, northern Hokkaidō (Epi-Jōmon).

Divergent Paths: Siberia and the Americas

By this period, the genetic separation was complete. Native American populations, descended from a subset of Paleo-Siberians that had crossed Beringia earlier, underwent rapid demographic expansion across the Americas.

This expansion involved:

-

Strong founder effects

-

Regional isolation

-

Ecological adaptation across diverse environments

Over millennia, these processes produced wide phenotypic diversity among Indigenous American populations—entirely consistent with long-term evolutionary dynamics and independent development.

Meanwhile, Siberia itself continued to receive new population influxes from East Asia, further distancing modern Siberians from their Paleo-Siberian predecessors.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Gradual cooling from mid-2nd millennium BCE; salmon cycles remained productive with occasional failures.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Riverine chiefdoms intensified control of salmon stations; multi-house compounds with storage pits.

-

Hokkaidō Epi-Jōmon maintained broad-spectrum foraging with pottery and shell middens; limited horticulture at southern margins late in the period.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Bronze and iron trickled in via Amur–Sungari–Koryo networks: small knives, ornaments; local tools still stone/bone/antler.

-

Sinew-backed bows; dogs for hauling; winter oil lamps and skin boats on the Okhotsk coast.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Amur–Sungari metal/horse trade; Sakhalin as bridge between mainland and Hokkaidō; coastal couriers along Okhotsk.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Chiefly feasts anchored diplomatic networks; bear and salmon rites continued; formalized cemetery rows reflect lineage memory.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Exchange-for-metal strategies augmented cutting and sewing efficiency; storage + mobility buffered salmon shortfalls.

Transition

On the eve of the 1st millennium BCE, river chiefs and coastal specialists stood poised to integrate novel tools and alliances that would culminate in later Okhotsk and Satsumon horizons.

Northern North America (2637 – 910 BCE): Copper and Slate, Salmon and Earthworks — Coast, River, and Desert Worlds

Regional Overview

From the Arctic sea-ice and salmon-flooded fjords of the North Pacific to the Great Lakes–Ohio valleys and the estuaries and deserts of the Gulf and West, Early Antiquity in Northern North America was defined by mobility, storage, and exchange.

Three great cultural theaters cohered without empire:

-

the Northwest, where ASTt bands in the Arctic coexisted with ranked plank-house polities on the Pacific coast;

-

the Northeast, where Woodland earthwork traditions and diversified river–coastal economies matured;

-

the Gulf & West, where estuaries, deserts, and Pacific littorals linked seasonal camps into wide resource webs.

Together they formed a continent-spanning mosaic of specialized ecologies joined by grease trails, canoe corridors, and reciprocity.

Geography & Environment

-

Northwest: Arctic Alaska’s Kotzebue–Norton coasts, Brooks Range interior, Cook Inlet–Prince William Sound, Haida Gwaii–Central Coast, and the Fraser–Columbia plateaus.

-

Northeast: Atlantic façade from Florida to Newfoundland, St. Lawrence–Great Lakes–Ohio–Mississippivalleys, Appalachian uplands, Hudson Bay rim, and the Eastern Arctic/Greenland margins.

-

Gulf & West: Gulf wetlands and estuaries, Colorado and Central California valleys, Sonoran–Mojave deserts, and southern Rockies/Sierra piedmonts.

Environmental contrasts—ice-edge seas, temperate rainforests, prairie-woodland ecotones, and dune–playa basins—drove seasonal movement and regional specialization.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Gradual late-Holocene cooling touched all three spheres.

-

Arctic sea-ice regimes structured hunting windows but salmon runs stayed reliable.

-

Northeastern woodlands stabilized around lake–river systems; coastal storms and estuarine productivity persisted.

-

Gulf & West oscillated between wetland surges and desert drought pulses; Pacific upwelling anchored fisheries.

Across the region, storage, multi-ecozone mobility, and trade redundancy were the principal buffers against climate variability.

Societies & Settlement

Northwest

-

Arctic Small Tool tradition (c. 2500–800 BCE): microblade toolkits, small semi-subterranean houses, high mobility—precursors to later Paleo-Inuit/Thule systems.

-

North Pacific Coast: ranked household polities in massive cedar plank dwellings controlled salmon weirs, canoe landings, and cedar stands; interior pit-house towns flourished along salmon canyons (Fraser/Columbia).

Northeast

-

Early–Middle Woodland trajectories seeded by Late Archaic: Adena → Hopewell earthwork ceremonialism in the Ohio and allied river valleys; dense fisheries around the Great Lakes; shell-heap villages along the Atlantic.

-

Horticulture expanded; maize diffusion began in the Midwest late in the span, complementing riverine stored foods.

Gulf & West

-

Gulf Coast: shellfish- and fish-rich estuaries supported large middens and seasonal mound sites.

-

Arid Southwest/Great Basin: early cultivation (squash, sunflower) complemented foraging; water storage and mobility were key.

-

California: acorn economies, salmon fisheries, and Channel Islands–coast exchange linked beadwork, fish products, and obsidian.

Economy & Technology

-

Metals: No bronze/iron industries; native copper cold-hammered in the Northwest and Northeast (Great Lakes copper sheets, NW Alaska awls/points).

-

Lithics: Ground slate knives and points proliferated on the North Pacific; obsidian (Edziza) traveled inland; widespread projectile point traditions persisted.

-

Boats: Skin boats and lamps in the Arctic; sewn-plank and dugout canoes on coasts and inland rivers; estuarine canoes in the Gulf and California.

-

Food systems: smoking/drying racks, plank or pit granaries, and earth ovens generalized food storage across regions—the continent’s key resilience technology.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Grease trails carried eulachon oil from coastal inlets to interior plateau towns; copper, slate, and labret styles circulated along the Gulf of Alaska.

-

Hopewell Interaction Sphere moved mica, obsidian, copper, marine shell among the Great Lakes–Ohio–Appalachian networks; coastal canoe routes linked Chesapeake–Delaware–Hudson–Gulf of Maine.

-

Gulf & Pacific corridors joined estuaries to deserts and islands: shell beads, fish products, pigments, and lithics moved between California, the Channel Islands, and interior valleys; along the Gulf, canoe coasting tied river mouths into a common littoral.

Belief & Symbolism

-

Northwest: first-salmon rites, sea-mammal ceremonies, and emergent crest/lineage identifiers in house art and grave goods.

-

Northeast: earthwork cosmology—Adena/Hopewell mounds with astronomical alignments; carved pipes, copper sheets, and mica mirrors in mortuary assemblages.

-

Gulf & West: shell ornaments, petroglyphs, and painted shelters; coastal and desert ritual emphasized water, game, and ancestral places.

Across regions, feasting, exchange, and mortuary offerings cemented alliances and stabilized resource sharing.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Arctic & Subarctic: ice-edge scheduling + salmon storage; driftwood logistics; multi-habitat seasonal rounds.

-

North Pacific Coast: ranked redistribution and stored salmon/eulachon oil smoothed shocks.

-

Northeast: diversified woodland subsistence and inter-regional alliances buffered failure.

-

Gulf & West: mobility between estuary, valley, and upland; water caching and drought-tolerant foraging; smoked/dried surplus against hurricanes and dry years.

Storage + mobility + exchange formed a continent-wide triad of resilience.

Regional Synthesis & Long-Term Significance

By 910 BCE, Northern North America had matured into a tripartite cultural mosaic:

-

Arctic ASTt traditions set the stage for Paleo-Inuit and Thule expansions;

-

North Pacific ranked house societies and interior salmon towns approached their classic florescence;

-

Woodland earthwork networks in the Northeast deepened, while Gulf & Western ecologies sustained diverse, specialized lifeways.

Copper and slate innovation, canoe corridors, and ritualized exchange bound these worlds together—a continental infrastructure of knowledge and movement that would support the medieval transformations described in later-epoch chapters.

Western Branches of the Arctic Small-Tool Tradition

West of 110°W, Arctic Small-Tool groups spread across Alaska, the western Canadian Arctic, and the Bering Strait corridor. Like their eastern counterparts, they mastered microlithic technology and portable shelters, but local adaptations emphasized both inland and coastal hunting.

In Alaska, small-blade toolkits supported mixed economies: caribou, fish, and seals along coastal margins. Seasonal mobility linked river valleys to sea ice. These ASTt communities set the stage for later Choris, Norton, and Ipiutak traditions, and ultimately the florescence of the Old Bering Sea culture.

By 910 BCE, the foundations of western Arctic lifeways—flexibility, mobility, and cross-Strait connections—were firmly in place.